Clinical features and histopathologic findings in BPS/IC with and without Hunner’s lesions

Ralph Peeker 2

1 Pathology, Ryhov Hospital Jönköping, Landvetter, Schweden

2 Department of Urology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Schweden

Abstract

Bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis is a condition with the leading clinical symptoms related to the bladder, such as pain and voiding frequency. The present understanding is that there are a variety of presentations representing different pathological entities, even though sharing similar symptomatology and the same chronic course. Only a subset of patients has bleeding lesions as seen in the cystoscope with bladder distension, previously described as ulcers, and microscopic changes with interstitial inflammation, fibrosis and mastocytosis. These findings are nowadays consistent with classic IC with Hunner’s lesions also designated as type 3C.

Summary of recommendations

Patients with bladder pain symptoms can be hard to treat. Studies over the years have shown that it is important to identify classic interstitial cystitis (IC) with Hunner’s lesions since this is a well treatable disease. Cystoscopic examination is mandatory; in classic IC typical changes, as discussed in this paper, includes an inflamed area with central vulnerable scars which rupture with increasing bladder distension while non-ulcer BPS displays a normal bladder mucosa at initial cystoscopy.

To make an unquestionable diagnosis, histopathology is required, too. Deep biopsies including bladder muscle is needed to diagnose classic IC, since the disease process involves superficial as well as deeper layers of the bladder wall. Important features to consider when making the histopathologic diagnosis are: denudation, ulceration, granulation tissue, fibrosis and mast cells in the urothelium as well as counts in the detrusor muscle.

1 What is interstitial cystitis?

Much has changed since the term interstitial cystitis (IC) was first introduced by Skene in 1887 [1]. An important step came almost exactly 100 years ago when Guy L. Hunner described a symptom complex of bladder pain associated with peculiar cystoscopic findings, later denominated the Hunner’s ulcers [2], at that time being tantamount to IC. A first stage in a change came 1949, when John Hand presented a large series of IC patients observing that IC did not comprise just the single entity with Hunner’s ulcers, claiming that other clinical presentations could be met [3]. Later on, in 1978, Messing and Stamey suggested that there might be an early form of the disease characterized by small submucosal bleedings, so-called glomerulations, potentially progressing into the well-known classic disease with Hunner’s ulcers [4], and after that extent, the diagnose became even wider. However, subsequent observations have not been able to confirm the progression of the ‘early form’ presentation into the classic ulcerous form, including the end stage disease (bladder contracture). Currently, we are continuing a circle of development again to realize that Hunner’s disease is a unique entity. The present understanding is that different presentations stand for different pathological entities, even though sharing similar symptomatology and the same chronic course [5], [6], [7], [8]. For example, a recent report by Killinger et al. failed to disclose any striking differences in pain patterns between the two subtypes [9]. Between the two main clinical (and cystoscopic) presentations, the differences are reflected in clinical manifestation and age distribution [7], [8], and it has also been reported that the two subtypes respond differently to many treatment procedures [8]. The notion of heterogeneity of the disease concept IC [5] was supported by observations by Koziol et al. based on US epidemiological data relating to demographics, risk factors, symptoms, pain and psychosocial factors [6]. Quite recently, Peters et al. demonstrated remarkable differences between the two subtypes in the number of comorbid diagnoses as well as symptoms [10].

In the last few years, important changes have taken place in ideas on cornerstones in IC diagnostics. During decades, the distribution of classic IC versus non-ulcer disease has been debated. Messing and Stamey stated that classic interstitial cystitis could account for about half of all patients with interstitial cystitis [4] in agreement with our notions [5], [6], [7], [8] while others found Hunner’s type to be a rare finding, accounting for 5–10% of cases of interstitial cystitis [11].

On the other hand, in their very large series. Koziol et al. noted classic interstitial cystitis in approximately 20 percent of cases [6]. That opinion of Hunner’s lesions disease being rare is a reasonable explanation of leaving identification out and to omit separation of this entity in clinical research, leading to doubtful usefulness of results, during several decades. Now, an increasing number of reports indicate that there is every reason to pay attention to this entity.

Cystoscopically, classic IC displays typical reddened mucosal areas often associated with small vessels radiating towards a central scar which ruptures with increasing bladder distension while non-ulcer IC displays a normal bladder mucosa at initial cystoscopy [5], [6], [7], [8]. Since the time of Hand, the finding of glomerulations has been regarded as a positive diagnostic sign. However remarkably, according to a recent critical review the finding of glomerulations is of little diagnostic consequence [12].

2 Bladder pain syndrome (BPS)

During the last decades, the nomenclature of the disease called interstitial cystitis has been debated. The leading clinical symptoms are pain related to the bladder and voiding frequency while inflammation of the bladder interstitium is found only in a subset of patients; in many cases it is hard to find the cause of origin of complaints. Therefore, a new terminology was needed, and several organisations (the European Society for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis/ESSIC, later International Society for the Study of Bladder Pain Syndrome, the European Association of Urology/EAU and the American Association of Urology/AUA) have agreed to the general term bladder pain syndrome (BPS) including interstitial cystitis, BPS/IC. In addition, the ESSIC has constructed a classification system with classical IC with Hunner’s lesions designated as type 3C.

3 General role of histopathological examination in BPS/IC

The primary role of histopathology in the diagnosis of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC) is one of excluding other possible diagnoses. Confusing and harmful conditions must be ruled out; carcinoma and carcinoma in situ, eosinophilic cystitis, tuberculous cystitis, as well as any other entities with a specific tissue diagnosis, such as metaplastic changes like enteric metaplasia, squamous cell metaplasia and nephrogenic metaplasia.

However, it is worth noting that biopsy retrieval and histopathological examination is also needed when it comes to diagnosing BPS/IC. Although most histopathology features are not distinctive in non-Hunner’s diseases, certain findings are specific for classic IC. The understanding of the properties of various cell systems has developed dramatically in recent decades and the diagnosis with standard staining procedures and light microscopy can now be reinforced and further refined with immunohistochemistry and even more sophisticated ancillary techniques.

4 What happens to the biopsy in the pathology laboratory?

If the clinician wants to get a correct histopathological diagnosis of BPS/IC, biopsies should preferably be obtained by transurethral resection of large and deep strips of the bladder wall, including the detrusor muscle; however, deep cold cup biopsies is also an acceptable option. The choice of biopsy technique is mostly depending on local routines, but the choice of biopsy retrieval technique is also influenced by the clinically suspected pathology and thus the pathology the clinician finds important to verify or exclude.

Formaldehyde fixation (4%, 10%) is compulsory and the fixation rate is approximately 1 mm per hour, meaning that small biopsies are fixated by the time they reach the pathology laboratory. Then the specimen is dehydrated, paraffin or wax embedded, and cut into series of 4 µm sections. Thereafter, the specimen is deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin/eosin (Htx-Eo) and mounted with coverslips. Other staining are often performed to make it easier for the pathologist. For instance, Van Gieson or Sirius can be used to demonstrate fibrosis. The specific antibody mast cell tryptase is nowadays preferred to visualise tryptase in mast cells. Toluidin Blue, a metachromatic dye, may also be used to stain mast cells but the staining procedure with Toluidin blue is tricky. This method is very dependent on low pH, mast cell containing heparin and chondroitin-sulfate to be visualized. Additional chemicals in this method like HCl, citric acid, as well as the dye Toludin blue is unhealthy for people handling the dying process. This method has now, in many laboratories, been replaced with a mast cell tryptase antibody capable of reveal an increased number of mast cells in the mucosa and the detrusor muscle (Figure 1).

visualized by Mab Tryptase (arrows). This case 80/mm²; magnification 100.

5 In the microscope

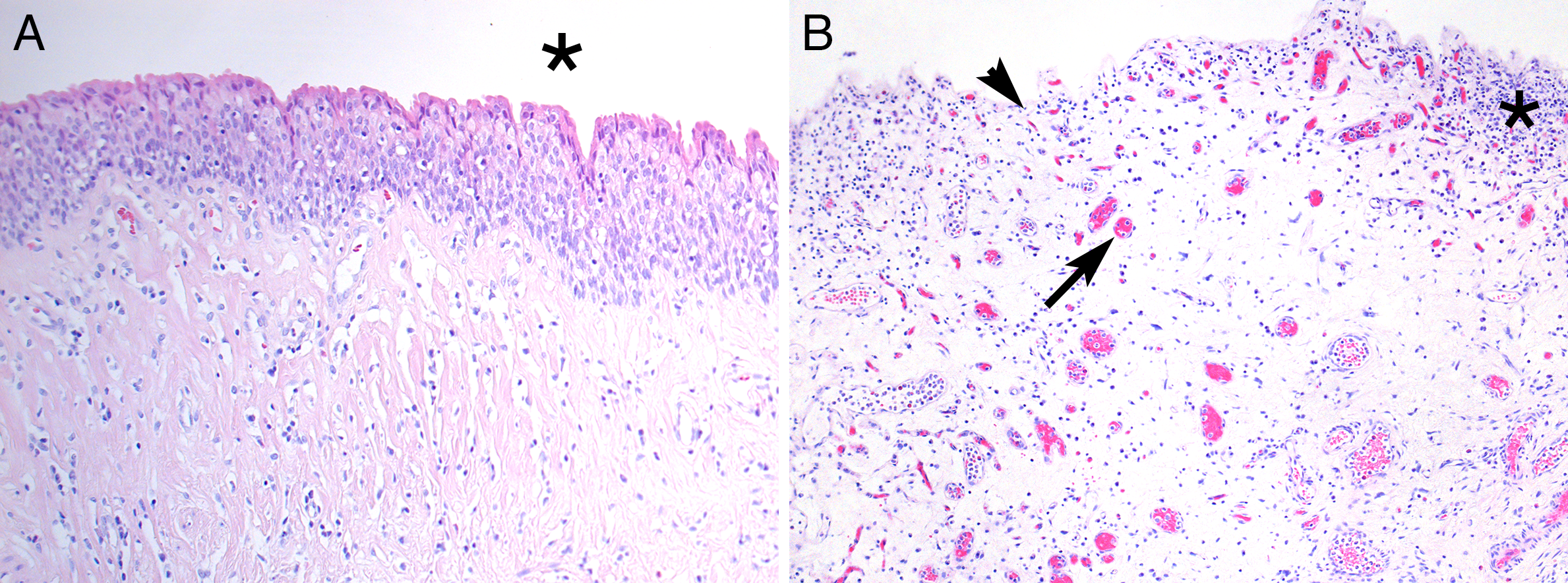

Bladder tissue from patients with BPS/IC type

Figure 2B: Abnormal bladder with denudation and erosion of the urothelium (arrowhead).

Accordingly, BPS/IC type 3C (classic IC) displays marked inflammatory changes in the lamina propria, including the presence of lymphocytes, plasma cells and mast cells. The detection of increased number of mast cell in the detrusor muscle is mandatory for the diagnosis. The mast cell count, using a grid, is usually high above 25 per mm² (Figure 1).

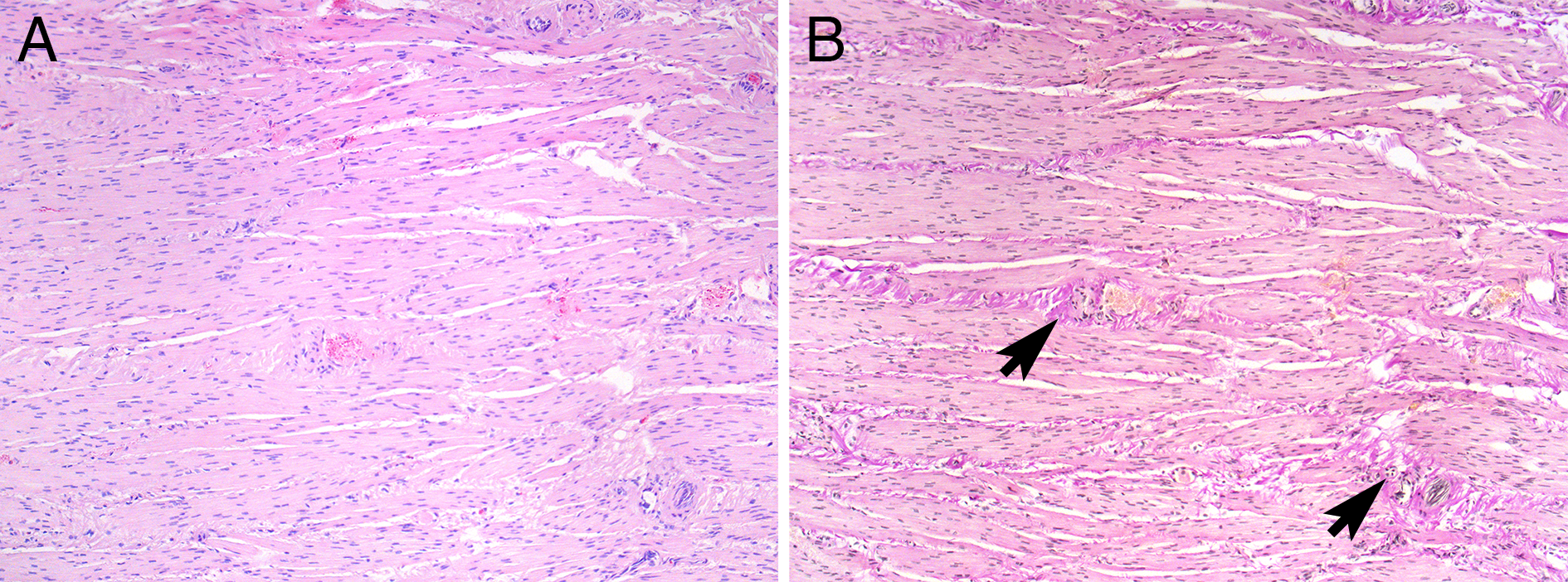

Fibrosis is always seen in BPS/IC type 3C, and especially inter- and intra-lamellar fibrosis in the detrusor muscle should be evaluated and reported (Figure 3A-B).

Figure 3B: Same consecutive slide coloured with Van Gieson showing sparse but diffuse intra lamellar fibrosis (arrows). Magnification 100.

The light microscopic features in BPS/IC type 3C differ markedly from what can be seen in non-Hunner’s BPS. In Lepinards report [15], ulcerative disease affected the three layers of bladder wall, but this was not the case in non-ulcerative disease, according to the terminology then. Another report, comprising 64 patients with ulcerative disease and 44 with nonulcerative IC, showed that ulcerative disease had mucosal ulceration and hemorrhage, granulation tissue, severe inflammatory infiltrates, high mast cell counts, and perineural infiltrates. Despite sharing a similar symptomatology and the same chronic course, the non-ulcer group had an almost unaffected mucosa with sparse inflammatory response, the main feature being mucosal ruptures and suburothelial haemorrhages [16], but often biopsies can be perfectly normal in non-Hunner’s BPS.

6 Ultrastructural electron microscopy studies

Electron microscopy has had limited success in the diagnostic work on BPS/IC. Collan et al. stated in an early paper that there was a significant similarity of the ultrastructure of epithelial cells between controls and IC patients [17], and around ten years later, Dixon et al. also failed to discover any differences in the histologic appearances of urothelial cells in patients with IC as compared to controls [18]. Neither could Anderström et al. see distinctive ultrastructural surface characteristics for IC, however, the proportion of cells covered by round, uniform, and pleomorphic microvilli was higher in the IC patients than in controls [19].

At variance with these reports, Elbadawi and Light concluded that ultrastructural changes appear to be sufficiently distinctive to be diagnostic in specimens submitted for pathologic confirmation of non-ulcer interstitial cystitis. A detailed ultrastructural study was performed on patients with non-ulcer disease [20]. The distinctive combination of peculiar muscle cell profiles, injury of intrinsic vessels and nerves in muscularis and suburothelium, and discohesive urothelium was observed in the classic IC and less markedly in non-ulcer samples of all specimens. A marked edema of various tissue elements and cells appeared to be a common attribute of many observed changes. Urothelial changes interrupted the true permeability barrier and neural changes included degenerative and regenerative features.

7 The role of mast cells in BPS/IC is still unresolved

The mast cell is regarded not only as a cell involved in allergic tissue reactions but also as a multifunctional immunocompetent cell, involved in a variety of tissue reactions such as chronic inflammation, examples of which are classic IC and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as fibrosis [21]. It has been shown that the mast cell, in addition to histamine and heparin, also contains other inflammatory mediators such as leucotrienes, cytokines, and the angiogenic and fibroblast stimulatory factor bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) [22], [23]. Not only allergen binding but also nerve-derived mediators may stimulate mast cell secretion [24], and the morphological association between mast cells and neuropeptide-containing nerves has been demonstrated [25], [26], [27].

In bladder specimens from patients with classic IC, non-Hunner’s BPS, and controls it has been demonstrated that mast cells can be visualised in several ways: metachromasia, reflecting glycosaminoglycan content, and immunohistochemistry, visualising tryptase, chymase and IL-6 as well as the surface markers CD 117 and stem cell factor (SCF) [28]. In that report, classic IC showed a 6-10-fold increase of mast cells in terms of proteinase positivity while non-ulcer IC only revealed twice as many mast cells as controls. Furthermore, in contrast to non-ulcer IC and controls, classic IC displayed an abundance of epithelial mast cells.

8 What about autoimmunity in BPS/IC?

Previously, the presence of autoantibodies in patients with IC have been reported repeatedly [29], [30], [31], and some of the common clinical and histopathological characteristics present in IC patients show specific similarities with other well-known autoimmune events. Therefore, speculatively, IC may arise from autoimmune disturbances. The role of autoimmunity in IC is still controversial, however, and the disease has so far not been demonstrated to originate from a direct autoimmune attack on the bladder, but rather it can be assumed that some of the autoimmune symptoms and pathologic findings arise indirectly, as a result of tissue destruction and inflammation from other yet unknown causes.

In a study of 47 patients, Mattila et al. found immune deposits in the vessel walls of 33 patients [32], and in a following study, they found electron microscopic evidence of endothelial injury in 14 out of 20 IC patients [33]. The inflammatory response in classic IC is of a chronic nature, and potentially there is a cell-mediated autoimmune response at hand. In a study comprising 24 classic IC patients, 9 non-ulcer patients, and 10 controls [34], it was found that the classic IC patients displayed aggregates of T-cells as well as B-nodules with focal germinal centres. There was either a decreased or normal helper/suppressor ratio, and suppressor cytotoxic cells were present in the germinal centres. On the other hand, the non-ulcer patients only showed slightly increased numbers of lymphoid cells, dominated by T-helper cells. The non-ulcer group did not differ significantly from the controls. In agreement with these findings, in a recently published paper by Maeda et al., patients with Hunner’s type interstitial cystitis (HIC) and non-Hunner’s type interstitial cystitis (NHIC) were compared [35] using immunohistochemical quantification of infiltrating T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes, and plasma cells. The authors were able to demonstrate that lymphoplasmacytic infiltration was significantly more severe in HIC samples than in NHIC samples. They also disclosed that the loss of residual epithelium was considerably decreased in HIC specimens but not in NHIC specimens. Complementary in situ hybridization of the light chains was performed to examine clonal B-cell expansion, and the authors demonstrated that such expansion of light-chain-restricted B-cells was observed in 31% of cases of HIC. Consequently, Maeda et al concluded that NHIC and HIC appear to be divergent pathological entities, the latter being characterized by pancystitis, frequent clonal B-cell expansion and epithelial denudation. They also used double-immunofluorescence for CXCR3 and CD138 to detect CXCR3 expression in plasma cells from subjects with HIC and NHIC, respectively. The authors studied the correlation between CXCR3 positivity and lymphocytic and plasma cell numbers and clinical parameters. The density of CXCR3-positive cells showed no apparent differences between HIC and non-IC cystitis samples although distribution of CXCR3-positivity in plasma cells indicated co-localization of CXCR3 with CD138 in HIC specimens, but not in non-IC cystitis specimens [36].

9 Nitric oxide metabolism and BPS/IC

Studies by us and others have suggested that nitric oxide (NO) metabolism might play an important role in this condition since the luminal production of NO is high in HIC but not so in NHIC [37], [38]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) has been demonstrated to be abundant in the urothelium and in inflammatory cells in patients with HIC, not only as determined by immunohistochemistry but also on the transcriptional level [39], [40].

10 Further research

A dominating clinical problem is the diversity of pathological mechanisms that can result in bladder pain and how to define recognizable phenotypes within this great number of possible entities; there is still no overall worldwide acceptance and consensus on classification [41]. One well definable phenotype, however, is classic IC with Hunner’s lesions [5], [7], [8], [42], but even when it comes to this diagnosis, there are discrepancies to be found when comparing different centres. Systematic cystoscopy training, use of markers (like NO), and broader engagement by pathologists will hopefully make interpretations more uniform. The desired team is the well-trained urologist working closely together with the devoted pathologist and in cooperation with a multidisciplinary group, when needed.

The histopathologic features of classic IC are characteristic and the interesting combination of cell elements, the association of inflammation to excessive evaporation of NO and production of other inflammatory markers might give clues to disease mechanisms, hopefully eventually resulting in the development of rational, pharmacological treatment.

11 Conclusion

BPS/Classic IC with Hunner’s lesions is a well-defined disease with characteristic cystoscopy and microscopy. It is important to identify this category among the great number of patients with bladder pain symptoms since it can be successfully treated with hydro-distention, intra-lesional cortisone injections, fulguration, or resection of bladder tissue. It is mandatory that urologists and pathologists who manage BPS are aware of this specific entity of patients: IC with Hunner’s lesions.

References

[1] Skene AJC. Diseases of Bladder and Urethra in Women. New York: Wm Wood; 1887.[2] Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer in women; report of cases. Boston Med Surg J. 1915;172:660-4. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM191505061721802

[3] Hand JR. Interstitial cystitis: Report of 223 cases (204 women and 19 men). J Urol. 1949;61(2):291-310. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)69067-0

[4] Messing EM, Stamey TA. Interstitial cystitis: early diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Urology. 1978 Oct;12(4):381-92. DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(78)90286-8

[5] Fall M, Johansson SL, Aldenborg F. Chronic interstitial cystitis: a heterogeneous syndrome. J Urol. 1987 Jan;137(1):35-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)43863-8

[6] Koziol JA, Adams HP, Frutos A. Discrimination between the ulcerous and the nonulcerous forms of interstitial cystitis by noninvasive findings. J Urol. 1996 Jan;155(1):87-90. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66551-0

[7] Logadottir Y, Fall M, Kåbjörn-Gustafsson C, Peeker R. Clinical characteristics differ considerably between phenotypes of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2012 Oct;46(5):365-70. DOI: 10.3109/00365599.2012.689008

[8] Peeker R, Fall M. Toward a precise definition of interstitial cystitis: further evidence of differences in classic and nonulcer disease. J Urol. 2002 Jun;167(6):2470-2. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65006-9

[9] Killinger KA, Boura JA, Peters KM. Pain in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: do characteristics differ in ulcerative and non-ulcerative subtypes? Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Aug;24(8):1295-301. DOI: 10.1007/s00192-012-2003-9

[10] Peters KM, Killinger KA, Mounayer MH, Boura JA. Are ulcerative and nonulcerative interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome 2 distinct diseases? A study of coexisting conditions. Urology. 2011 Aug;78(2):301-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.04.030

[11] Parsons CL. Interstitial cystitis: Clinical manifestations and diagnostic criteria in over 200 cases. Neurourol Urodyn. 1990;9(3):241-50. DOI:10.1002/nau.1930090302

[12] Wennevik GE, Meijlink JM, Hanno P, Nordling J. The Role of Glomerulations in Bladder Pain Syndrome: A Review. J Urol. 2016 Jan;195(1):19-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.112

[13] Johansson SL, Ogawa K, Fall M. The Pathology of Interstitial Cystitis. In: Sant GR, editor. Interstitial cystitis. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. p. 143-52.

[14] Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer: further notes, with a report of eighteen cases. JAMA. 1918 Jan 26;70(4):203-12. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1918.02600040001001

[15] Lépinard V. La cystite interstitielle [Interstitial cystitis]. Ann Urol (Paris). 1998;32(6-7):349-51.

[16] Johansson SL, Fall M. Clinical features and spectrum of light microscopic changes in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1990 Jun;143(6):1118-24. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)40201-1

[17] Collan Y, Alfthan O, Kivilaakso E, Oravisto KJ. Electron microscopic and histological findings on urinary bladder epithelium in interstitial cystitis. Eur Urol. 1976;2(5):242-7. DOI: 10.1159/000472019

[18] Dixon JS, Holm-Bentzen M, Gilpin CJ, Gosling JA, Bostofte E, Hald T, Larsen S. Electron microscopic investigation of the bladder urothelium and glycocalyx in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1986 Mar;135(3):621-5. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)45763-6

[19] Anderström CR, Fall M, Johansson SL. Scanning electron microscopic findings in interstitial cystitis. Br J Urol. 1989 Mar;63(3):270-5. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1989.tb05188.x

[20] Elbadawi AE, Light JK. Distinctive ultrastructural pathology of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis: new observations and their potential significance in pathogenesis. Urol Int. 1996;56(3):137-62. DOI: 10.1159/000282832

[21] Hunt LW, Colby TV, Weiler DA, Sur S, Butterfield JH. Immunofluorescent staining for mast cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: quantification and evidence for extracellular release of mast cell tryptase. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992 Oct;67(10):941-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)60924-0

[22] Qu Z, Liebler JM, Powers MR, Galey T, Ahmadi P, Huang XN, Ansel JC, Butterfield JH, Planck SR, Rosenbaum JT. Mast cells are a major source of basic fibroblast growth factor in chronic inflammation and cutaneous hemangioma. Am J Pathol. 1995 Sep;147(3):564-73.

[23] Stevens RL, Austen KF. Recent advances in the cellular and molecular biology of mast cells. Immunol Today. 1989 Nov;10(11):381-6. DOI: 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90272-7

[24] Williams RM, Bienenstock J, Stead RH. Mast cells: the neuroimmune connection. Chem Immunol. 1995;61:208-35. DOI: 10.1159/000319288

[25] Keith IM, Jin J, Saban R. Nerve-mast cell interaction in normal guinea pig urinary bladder. J Comp Neurol. 1995 Dec;363(1):28-36. DOI: 10.1002/cne.903630104

[26] Naukkarinen A, Harvima IT, Aalto ML, Harvima RJ, Horsmanheimo M. Quantitative analysis of contact sites between mast cells and sensory nerves in cutaneous psoriasis and lichen planus based on a histochemical double staining technique. Arch Dermatol Res. 1991;283(7):433-7.

[27] Newson B, Dahlström A, Enerbäck L, Ahlman H. Suggestive evidence for a direct innervation of mucosal mast cells. Neuroscience. 1983 Oct;10(2):565-70. DOI: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90153-7

[28] Peeker R, Enerbäck L, Fall M, Aldenborg F. Recruitment, distribution and phenotypes of mast cells in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2000 Mar;163(3):1009-15. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67873-1

[29] Ochs RL, Stein TW Jr, Peebles CL, Gittes RF, Tan EM. Autoantibodies in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1994 Mar;151(3):587-92. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)35023-1

[30] Oravisto KJ. Interstitial cystitis as an autoimmune disease. A review. Eur Urol. 1980;6(1):10-3. DOI: 10.1159/000473278

[31] Silk MR. Bladder antibodies in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1970 Mar;103(3):307-9. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)61948-7

[32] Mattila J, Pitkänen R, Vaalasti T, Seppänen J. Fine-structural evidence for vascular injury in patients with interstitial cystitis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1983;398(3):347-55. DOI: 10.1007/BF00583590

[33] Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv Immunol. 1989;44:93-151. DOI: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60641-0

[34] Harrington DS, Fall M, Johansson SL. Interstitial cystitis: bladder mucosa lymphocyte immunophenotyping and peripheral blood flow cytometry analysis. J Urol. 1990 Oct;144(4):868-71. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)39611-8

[35] Maeda D, Akiyama Y, Morikawa T, Kunita A, Ota Y, Katoh H, Niimi A, Nomiya A, Ishikawa S, Goto A, Igawa Y, Fukayama M, Homma Y. Hunner-Type (Classic) Interstitial Cystitis: A Distinct Inflammatory Disorder Characterized by Pancystitis, with Frequent Expansion of Clonal B-Cells and Epithelial Denudation. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0143316. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143316

[36] Akiyama Y, Morikawa T, Maeda D, Shintani Y, Niimi A, Nomiya A, Nakayama A, Igawa Y, Fukayama M, Homma Y. Increased CXCR3 Expression of Infiltrating Plasma Cells in Hunner Type Interstitial Cystitis. Sci Rep. 2016 Jun;6:28652. DOI: 10.1038/srep28652

[37] Ehrén I, Hosseini A, Herulf M, Lundberg JO, Wiklund NP. Measurement of luminal nitric oxide in bladder inflammation using a silicon balloon catheter: a novel minimally invasive method. Urology. 1999 Aug;54(2):264-7. DOI: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00120-X

[38] Logadottir YR, Ehren I, Fall M, Wiklund NP, Peeker R, Hanno PM. Intravesical nitric oxide production discriminates between classic and nonulcer interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2004 Mar;171(3):1148-50. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110501.96416.40

[39] Koskela LR, Thiel T, Ehrén I, De Verdier PJ, Wiklund NP. Localization and expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in biopsies from patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2008 Aug;180(2):737-41. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.184

[40] Logadottir Y, Hallsberg L, Fall M, Peeker R, Delbro D. Bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis ESSIC type 3C: high expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in inflammatory cells. Scand J Urol. 2013 Feb;47(1):52-6. DOI: 10.3109/00365599.2012.699100

[41] Nordling J, Fall M, Hanno P. Global concepts of bladder pain syndrome (interstitial cystitis). World J Urol. 2012 Aug;30(4):457-64. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-011-0785-x

[42] van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, Bouchelouche K, Cervigni M, Daha LK, Elneil S, Fall M, Hohlbrugger G, Irwin P, Mortensen S, van Ophoven A, Osborne JL, Peeker R, Richter B, Riedl C, Sairanen J, Tinzl M, Wyndaele JJ. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol. 2008 Jan;53(1):60-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.09.019