Fournier’s gangrene: population-based epidemiology and outcomes

John N. Krieger 2

1 Department of Urology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, United States

2 Section of Urology, University of Washington, Seattle, United States

Abstract

Purpose: Case series reported 20–40% mortality rates for patients with Fournier’s gangrene with some series as high as 88%. This literature comes almost exclusively from referral centers.

Materials and Methods: We identified and analyzed inpatients with Fournier’s gangrene who had a surgical debridement or died in the US State Inpatient Databases.

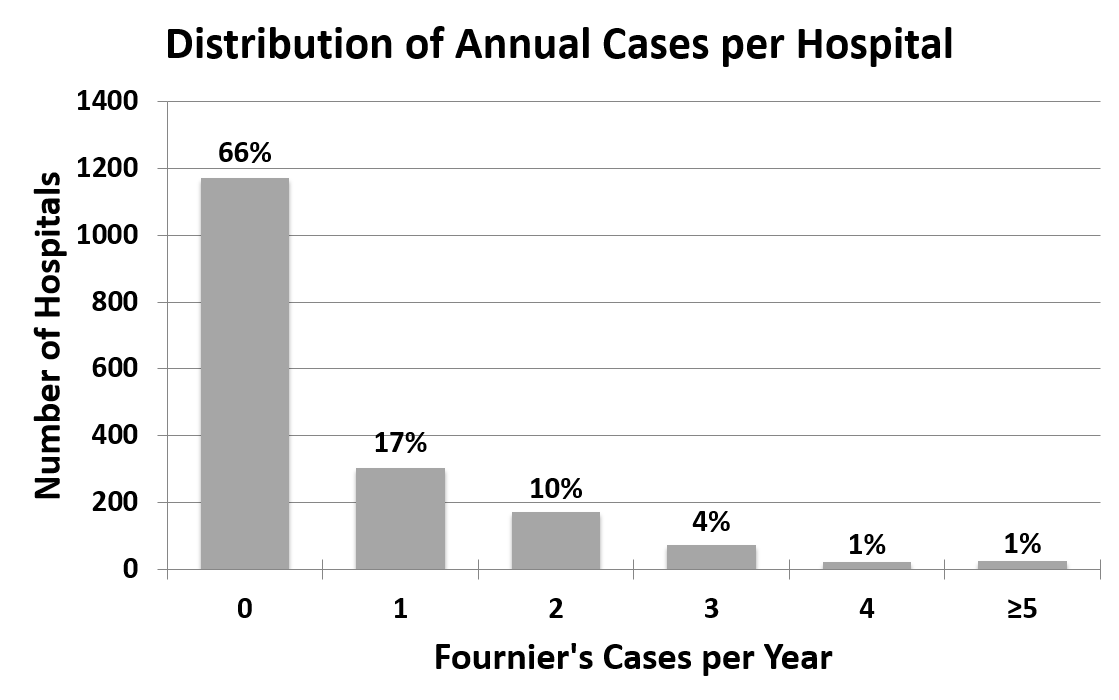

Results: 1,641 males and 39 females with Fournier’s gangrene represented <0.02% of hospital admissions. Overall, the incidence was 1.6 cases per 100,000 males and case fatality was 7.5%. 66% of hospitals cared for no cases per year, 17% cared for 1 case per year, 10% cared for 2 cases per year, 4% cared for 3 cases per year, 1% cared for 4 cases per year, and only 1% cared for ≥5 cases per year. Teaching hospitals had higher mortality (aOR 1.9) due primarily to more acutely ill patients. Hospitals treating more than 1 Fournier’s gangrene case per year had an adjusted 42–84% lower mortality (p<0.0001).

Conclusions: Most hospitals rarely care for Fournier’s gangrene patients. The population-based mortality rate (7.5%) was substantially lower than case series from tertiary care centers. Hospitals that treated more Fournier’s gangrene patients had lower mortality rates supporting the rationale for regionalized care for patients with this rare disease.

Summary of recommendations

- In this population-based study in the United States, the incidence and case fatality rate is lower than previously published.

- Most hospitals rarely care for patients with Fournier’s gangrene in a given year, but there was a clear decrease in patient mortality at hospitals that cared for greater numbers of patients with this condition supporting arguments in favor of regionalization of care.

- Early recognition, broad-spectrum antibiotics, aggressive surgical debridement, and resuscitation/supportive care remain the cornerstones of care for patients with Fournier’s gangrene.

1 Introduction

In 1883 Jean Alfred Fournier described idiopathic gangrene in previously healthy young men with acute onset and rapid progression [1]. This definition has changed substantially. Today, an etiology can almost always be identified, and the disease is not limited to young males [2], [3]. Fournier’s gangrene is a urologic emergency characterized by progressive necrotizing infection of the external genitalia or perineum [1]. Standard teaching is that management depends on early recognition, broad-spectrum antibiotics, resuscitation and aggressive debridement [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

The literature reports 20–40% mortality rates with some studies reporting mortality as high as 88% (Table 1) [6]. These reports tend to be from tertiary referral centers with most studies being less than 100 patients [7]. It is difficult to generalize these findings to other practice settings. Previous reports also reflect differences in referral patterns, surgical management, clinical volumes, and institutional differences. For example, authors diverge widely in their recommendations for urinary and fecal diversion, use of hyperbaric oxygen, and early skin grafting [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Because previous reports do not include data from community hospitals, there are no population-based data on incidence, regional trends, or case fatality rates. There have been efforts to predict mortality such as the Fournier’s Gangrene Severity Index that uses vital signs and laboratory tests to calculate a score [12], [13]. This index was based on data from only 30 patients presenting to a referral center over a 15 year period. Other investigators reported variable accuracy using the Fournier’s Gangrene Severity Index to predict mortality [14], [15], [16], [17], [18].

We used a large population-based database to better understand the epidemiology and outcomes of Fournier’s gangrene. Our initial goals were to determine the incidence, patient characteristics, and hospital experience with Fournier’s gangrene. We hypothesized that case series from tertiary referral centers do not accurately reflect the clinical spectrum and outcomes in the general population. The database was then used to examine differences in case severity and management between teaching and non-teaching hospitals, and to determine predictors of mortality in Fournier’s gangrene.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

The US State Inpatient Databases (SID) was established by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The SID includes data from 100% of admissions and discharges from all US civilian hospitals in participating states [19]. The SID is the largest US hospital care dataset.

We analyzed data from 13 states for 2001 and from 21 states for 2004. In 2001 data were purchased from Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Massachusetts, Maryland, Maine, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and West Virginia. For 2004 we also purchased data from Arizona, Kentucky, Michigan, Nebraska, Nevada, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin; but data from Maine were unavailable.

2.2 Case definition and data abstraction strategy

The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) code [20] for Fournier’s gangrene (608.83) is listed under “Diseases of the Male Genital Organs”. There is no Fournier’s gangrene code for females. To identify female cases, we searched for patients with diagnosis codes for gangrene (785.4) and either vulvovaginal gland abscess (616.3) or vulvar abscess (616.4).

Of the 10.7 million males in the SID for the years and states analyzed, the ICD-9 Fournier’s gangrene code (608.83) identified 2,238 cases [20], [21]. Because early debridement is essential [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], cases were required to have had a genital or perineal debridement, unless they died in the hospital. Debridements in the anatomic areas of interest were defined by ICD-9 procedure codes (48.8–48.82, 48.9, 49.0, 49.01, 49.02, 49.04, 49.39, 49.93, 54.0, 54.3, 61.0–61.99, 62.0–62.19, 62.2–62.42, 63.3, 63.4, 64.0, 64.2, 64.3, 64.92, 64.98, 71.0, 71.09, 71.22, 71.24, 71.29, 71.3, 71.5, 71.6–71.62, 71.8, 71.9, 83.0–83.09, 83.19, 83.21, 83.3–83.39, 83.4, 83.42, 83.44–83.49, 86.0, 86.04, 86.09, 86.22, 86.28, 86.3, 86.4, 86.9, 86.99). Overall 597 cases were excluded because they were discharged alive without undergoing a surgical debridement. Of the remaining 1,641 cases, 995 (61%) came from states that reported the number of distinct operating room visits. Using the ICD-9 procedure codes, the average number of genital/perineal debridements per admission was determined. To investigate surgical management, we determined the frequency of suprapubic tube placement, penectomy, orchiectomy, colostomy, and surgical wound closure with or without skin grafting. Of the 15.1 million females in the dataset, only 42 were identified with a diagnosis of gangrene (785.4) and either vulvovaginal gland abscess (616.3) or vulvar abscess (616.4). Overall 3 cases were excluded as they were discharged alive without a surgical debridement, leaving 39 total females with Fournier’s gangrene. Due to the differential identification and the low yield, analyses of female Fournier’s gangrene cases were limited to demographic and descriptive factors.

To evaluate the potential role of comorbidities on outcome, the Charlson comorbidity index was calculated for each patient. This represents the most extensively studied index for risk adjustment and mortality prediction [22], [23], [24], [25]. To more specifically examine the effect of specific comorbidities individual covariates were analyzed including: preexisting obesity, diabetes, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, renal failure, liver disease, AIDS, coagulopathy, peptic ulcer disease, and anemia.

2.3 Data analyses

Population-based incidence rates were calculated using US Census Bureau data [26]. Incidence and mortality rates were determined for the four US Census Bureau-defined regions (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West) [27]. Trends were compared to the 2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System prevalence rates for diabetes and obesity using linear regression analyses [28].

Although most patient and hospital demographic variables were obtained from the SID, some variables were obtained by linking hospital identification numbers with the National Inpatient Sample, a separate database also operated by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Because age was not linearly associated with mortality, age was categorized as <40, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70 years. Fournier’s gangrene cases treated at an institution was categorized as 0, 1, 2–4, 5–9, or ≥10 cases per year due to a non-normal case distribution. The Chi-squared test was used to evaluate binary variables, Student’s t-test allowing for unequal variance was used to evaluate continuous variables, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum was used to compare medians. Multivariate logistic regression analyses with robust standard errors were used to determine patient and hospital factors that predicted mortality adjusted for confounding variables.

3 Results

3.1 Patient and hospital demographics

We identified 1,641 males with Fournier’s gangrene. The overall case fatality rate was 7.5% (124 deaths/1,641 cases). Male cases had a mean age of 50.9±18.6 years, were most commonly white, and many had comorbidities (Table 2). Fournier’s gangrene patients were more likely to have diabetes (OR 3.3, 95% CI 2.9–3.7) and obesity (OR 3.7, 95% CI 3.1–4.3) than other males in the SID after adjustment for age (Table 2). Males with Fournier’s gangrene had similar rates of hypertension (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8–1.0), tobacco and alcohol use (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.8–1.2) and were less likely to use illicit drugs (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.8).

| Patient demographics | Male Fournier’s cases | All other males in SID | P value | |

| N=1,641 | N=11.2 million | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| |

<40 | 379 (23%) | 3,606,816 (32%) | <0.0001 |

| 40–49 | 341 (21%) | 1,286,656 (12%) | ||

| 50–59 | 407 (25%) | 1,481,863 (13%) | ||

| 60–69 | 250 (15%) | 1,584,606 (14%) | ||

| ≥70 | 264 (16%) | 3,224,827 (29%) | ||

| Mean age ± SD | 50.9±18.6 | 48.5±28.3 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| |

White | 836 (51%) | 6,042,041 (54%) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 307 (19%) | 1,316,227 (12%) | ||

| Hispanic | 109 (7%) | 801,713 (7%) | ||

| Other | 49 (3%) | 477,827 (4%) | ||

| Mean Charlson comorbidity index ± SD | 1.2±1.4 | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| |

Diabetes | 37% | 14% | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 11% | 4% | <0.0001 | |

| Hypertension | 31% | 31% | 0.64 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 5% | 3% | <0.0001 | |

| Tobacco Smoker | 15% | 15% | 0.69 | |

| Illicit Drug abuse | 1.5% | 2.3% | 0.0007 | |

| Admission source | ||||

| Transferred from outside Hospital | 110 (7%) | 451,481 (4%) | <0.0001 | |

| Case Fatality rate | 124 (7.5%) | 298,313 (2.7%) | <0.0001 | |

| *numbers may not add to 100% due to missing values | ||||

Only 39 women were identified who met our case definition for Fournier’s gangrene. Females with Fournier’s gangrene were similar to male cases in age, ethnicity, comorbidities, number of surgical debridements, and discharge needs. Female cases were more acutely ill at presentation as they had double the requirement for mechanical ventilation and dialysis, longer mean and median length of stay, greater total hospital charges and higher case fatality (12.8%, 5/39 cases) than the male cases, although none of these factors met statistical significance.

Admissions for Fournier’s gangrene were rare, representing less than 0.02% of all SID hospital admissions. The 1,764 hospitals analyzed cared for an average of 0.6±1.2 Fournier’s gangrene cases per year (median 0, range 0–23), while 66% cared for no Fournier’s gangrene cases during the 2 study years (Figure 1). Results were similar when 2001 and 2004 data were analyzed individually.

3.2 Epidemiology and regional trends

The overall incidence was 1.6 Fournier’s gangrene cases per 100,000 males annually (Table 3). The incidence peaked and remained steady after age 50 at 3.3 cases per 100,000 males.

| Incidence rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Fournier’s cases | Total male population in SID | Incidence rate per 100,000 males |

| 0–9 | 36 | 14,050,384 | 0.3 |

| 10–19 | 83 | 14,864,893 | 0.6 |

| 20–29 | 85 | 14,187,958 | 0.6 |

| 30–39 | 175 | 15,238,114 | 1.1 |

| 40–49 | 341 | 15,905,127 | 2.1 |

| 50–59 | 407 | 12,363,771 | 3.3 |

| 60–69 | 250 | 7,685,933 | 3.3 |

| ≥70 | 264 | 8,093,712 | 3.2 |

| Total | 1,641 | 102,389,892 | 1.6 |

The incidence of Fournier’s gangrene was highest in the South and the lowest in the West and Midwest US (Table 4). Fournier’s gangrene incidence increased 0.2 per 100,000 males for each 1% increase in the regional prevalence of diabetes (p=0.02). The incidence was not related to the regional prevalence of obesity (p=0.95). The regional mortality rate was not related to the regional prevalence of diabetes (p=1.00) or obesity (p=0.35). Similar findings were observed when individual states were analyzed, rather than US regions.

| US Region: | Male cases | Total male population in SID | Male incidence per 100,000 | Mortality rate | Estimated diabetes prevalence* | Estimated obesity prevalence* |

| N=1,641 | 102,389,892 | |||||

| Northeast | 651 | 39,850,544 | 1,6 | 8.8% | 7.1% | 22.3% |

| Midwest | 150 | 11,451,728 | 1,3 | 6.7% | 7.4% | 26.5% |

| South | 567 | 30,532,528 | 1,9 | 6.2% | 9.1% | 27.1% |

| West | 273 | 20,555,092 | 1,3 | 8.1% | 6.3% | 22.9% |

| *2005 Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System prevalence rates by region | ||||||

Transferred patients were similar in age, ethnicity, surgical procedures, length of stay, total hospital charges, and discharge needs to patients who were not transferred. There was a higher case fatality rate among transferred cases (12.7%) than cases that were not transferred (7.1%, p=0.09).

The 633 patients with a diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene that did not undergo debridement prior to discharge had lower mortality (5%), were less likely to require ICU care, mechanical ventilation, or dialysis, had an average length of stay almost half as long (7 vs. 13 days), and many patients were observed overnight and discharged the following day. These observations led us to conclude that the survivors from this group were unlikely to truly have a necrotizing soft tissue infection and, thus, were appropriately excluded.

3.3 Hospital demographics

The 1,641 male Fournier’s gangrene cases were treated at 593 hospitals. patients were more likely to be treated at large, urban hospitals (Table 5). Only 18% of the 1,720 hospitals in the SID were designated as teaching hospitals but they treated more than half of the Fournier’s gangrene cases. Overall, 71% of the teaching hospitals treated at least one Fournier’s gangrene case compared to only 30% of the non-teaching hospitals.

| Hospital Demographics | Number of cases* (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital location | ||

| Urban | 1,404 (86%) | |

| Rural | 126 (8%) | |

| Hospital bed size | ||

| Small | 128 (8%) | |

| Medium | 364 (22%) | |

| Large | 1,038 (63%) | |

| Hospital ownership | ||

| Non-profit | 532 (32%) | |

| Private | 163 (10%) | |

| Public | 117 (7%) | |

| Government | 718 (44%) | |

| Teaching hospital | 820 (50%) | |

| *Numbers may not add to 100% due to missing values | ||

3.4 Clinical management

Patients required multiple surgeries (average of 2.2±1.6, range 0-11), and multiple debridements (average of 1.5±1.0, range 0–8) per admission. Many patients required additional procedures (e.g., suprapubic tube, colostomy, orchiectomy, penectomy, etc.), while 10% required mechanical ventilation, and 1.4% underwent dialysis. Overall, 7% of patients underwent reconstruction of their wound (with or without skin grafting) during their hospitalizations. The median hospital stay was 8 days. Hospital charges were more than 50% higher for those who died than for those who survived (median $40,871 vs. $26,574, p=0.0001). After discharge 30% of Fournier’s gangrene cases required home health care or a skilled nursing facility stay.

3.5 Teaching hospitals versus non-teaching hospitals

Most Fournier’s gangrene cases were treated at teaching hospitals and these patients were younger, more likely to be nonwhite, and more often admitted via transfer (Table 6). Patients treated at teaching hospitals had more severe disease. They underwent more surgeries (especially genital/perineal debridements), mechanical ventilation, had longer lengths of stay, and higher total hospital charges. The case fatality rate at teaching hospitals was 8.9% compared to 6.4% at non-teaching hospitals (p=0.06, unadjusted).

| Teaching hospitals N=215 |

Non-teaching hospitals N=362 |

P value | ||

| Fournier’s gangrene cases, Number (%)† | 820 (50%) | 710 (43%) | ||

| Case demographic characteristics | ||||

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 49.7 ± 18.8 | 52.1 ± 18.7 | 0.05 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 59% | 72% | <0.001 |

|

| Black | 28% | 17% | ||

| Hispanic | 8% | 9% | ||

| Other | 5% | 2% | ||

| Admission Source | ||||

| Transferred from another hospital | 11% | 2% | <0.001 | |

| Hospital demographic characteristics | ||||

| Hospital location | ||||

| Urban | 98% | 85% | <0.001 |

|

| Rural | 2% | 15% | ||

| Hospital bed size | ||||

| Small | 7.7% | 9.2% | 0.03 |

|

| Medium | 21.5% | 26.5% | ||

| Large | 70.9% | 64.4% | ||

| Hospital ownership | ||||

| Non-profit | 26% | 45% | <0.001 |

|

| Private | 0.4% | 23% | ||

| Public | 7% | 9% | ||

| Government/Other | 67% | 24% | ||

| Number of Annual Fournier’s gangrene cases | ||||

| 1 | 9% | 26% | <0.001 |

|

| 2–4 | 53% | 71% | ||

| 5–9 | 26% | 4% | ||

| ≥10 | 12% | 0% | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | ||

| Management factors during each admission | ||||

| Mean total surgeries ± SD* | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | |

| Mean genital/perineal debridements ± SD* | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.001 | |

| Additional surgical procedures | ||||

| Suprapubic tube placement | 7% | 8% | 0.49 | |

| Colostomy | 10% | 8% | 0.09 | |

| Orchiectomy | 24% | 30% | <0.01 | |

| Penectomy | 1% | 1% | 0.98 | |

| Surgical wound closure | 11% | 4% | <0.001 | |

| Supportive care | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 13% | 8% | <0.01 | |

| Dialysis | 0.7% | 1.8% | 0.06 | |

| Median length of stay | 10 days | 7 days | <0.0001 | |

| Median total hospital charges | $31,900 | $22,862 | <0.0001 | |

| Case fatality rate | 8.9% | 6.4% | 0.06 | |

| † No information on teaching hospital status was available for 16 hospitals (3%) treating 111 (7%) of the Fournier’s gangrene cases * Mean ± SD number of surgeries and debridements were calculated based on the 61% cases where the dates of surgical intervention were reported |

||||

3.6 Mortality predictors

In univariate analyses, increasing age (OR 4.0 to 18.8) was associated with increased mortality (Table 7). Mortality increased 50% for each one-point increase in Charlson comorbidity (p<0.001). Four specific comorbidities were associated with increased mortality: hypertension (OR 1.5), congestive heart failure (OR 3.7), renal failure (OR 5.3), and coagulopathy (OR 4.4). On univariate analyses, hospital ownership and admission via transfer were associated with mortality. Mortality was higher with increased length of stay (OR 1.6% per day). There was a suggestion that patients presenting to urban institutions and teaching hospitals had increased mortality (both p=0.06). The number of Fournier’s gangrene cases treated per year did not predict mortality in unadjusted analyses.

| OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Patient-associated factors | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| <40 | Ref | <0.001 | |

| 40–49 | 4.0 (1.3–12.3) | ||

| 50–59 | 7.5 (2.6–21.4) | ||

| 60–69 | 13.8 (4.8–39.4) | ||

| ≥70 | 18.8 (6.7–53.1) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | Ref | 0.60 | |

| Black | 0.70 (0.41–1.20) | ||

| Hispanic | 1.01 (0.49–2.10) | ||

| Other | 0.73 (0.22–2.43) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) per 1 point increased index | <0.001 | |

| Specific comorbidities* | |||

| Diabetes | 0.94 (0.64–1.37) | 0.74 | |

| Obesity | 0.64 (0.32–1.30) | 0.22 | |

| Hypertension | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 0.05 | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 3.7 (2.3–5.8) | <0.001 | |

| Renal Failure | 5.3 (3.2–8.7) | <0.001 | |

| Coagulopathy | 4.4 (2.4–8.1) | <0.001 | |

| Hospital-associated factors | |||

| Bedsize | |||

| Small | Ref | 0.88 | |

| Medium | 1.19 (0.55–2.58) | ||

| Large | 1.09 (0.53–2.23) | ||

| Urban Hospital | 2.68 (0.97–7.38) | 0.06 | |

| Hospital ownership | |||

| Private, non-profit | Ref | 0.02 | |

| Private for profit | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) | ||

| Public | 1.4 (0.6–3.2) | ||

| Government/Other | 2.1 (1.3–3.4) | ||

| Teaching Hospital | 1.4 (0.98–2.12) | 0.06 | |

| Admission source | |||

| Transferred from another hospital | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) | 0.04 | |

| Cases Fournier’s gangrene (per year) | |||

| 1 | Ref | 0.55 | |

| 2–4 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | ||

| 5–9 | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | ||

| ≥10 | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | ||

| Length of stay (each day) | 1.6% (0.7–2.5%/day) per day | 0.001 | |

| Management variables | |||

| Each surgical debridement | 1.27 (1.1–1.5) per debridement | 0.001 | |

| Surgical procedures | |||

| Suprapubic tube placement | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) | 0.29 | |

| Colostomy | 1.9 (1.2–3.2) | 0.01 | |

| Orchiectomy | 0.31 (0.16–0.58) | <0.001 | |

| Penectomy | 3.2 (1.1–9.9) | 0.04 | |

| Wound closure | 0.63 (0.27–1.47) | 0.29 | |

| Supportive care | |||

| Mechanical ventilation | 8.2 (5.5–12.1) | <0.001 | |

| Dialysis | 10.1 (4.3–23.6) | ||

| *Additional comorbid conditions were evaluated and were not significant including: preexisting peripheral vascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, AIDS, peptic ulcer-disease, and anemia. | |||

Each operation that a patient required also increased the unadjusted odds of death by 27%, likely reflecting more severe Fournier’s gangrene. Certain procedures had an increased mortality: colostomy (OR 1.9), penectomy (OR 3.2), mechanical ventilation (OR 8.2), and dialysis (OR 10.1) during admission, suggesting more severe infection at admission.

On multivariate analyses, patient factors that independently predicted mortality included: increasing age category (aOR 4.0 to 15.0), Charlson comorbidity index (aOR 1.20 per point), and admission via transfer (aOR 1.9), after adjusting for hospital location, size, ownership, US region, teaching center status and number of Fournier’s gangrene cases treated annually (Table 8). When comorbidities were analyzed separately, specific risks associated with increased mortality included: heart failure (aOR 2.1), renal failure (aOR 3.2), and coagulopathy (aOR 3.4). Race and number of surgeries did not predict mortality.

| aOR (95% CI)* | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-related^ | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| <40 | Ref | <0.0001 | |

| 40–49 | 4.0 (1.1–14.1) | ||

| 50–59 | 7.3 (2.2–24.7) | ||

| 60–69 | 11.0 (3.1–38.9) | ||

| 70+ | 15.0 (4.5–49.7) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 1.20 (1.0–1.4) per point | 0.04 | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 2.1 (1.1–3.8) | 0.02 | |

| Renal failure | 3.2 (1.6–6.4) | 0.001 | |

| Coagulopathy | 3.4 (1.6–7.4) | 0.002 | |

| Admission via transfer | 1.9 (1.0–3.7) | 0.048 | |

| Hospital-related† | |||

| Fournier’s cases per year | |||

| 1 | Ref | <0.0001 | |

| 2–4 | 0.53 (0.30–0.95) | ||

| 5–9 | 0.58 (0.27–1.24) | ||

| ≥10 | 0.16 (0.04–0.66) | ||

| Teaching center status | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | 0.01 | |

| *Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) ^Patient-related predictors were adjusted for hospital location, US region, hospital bed size, hospital ownership, teaching center status, and cases of Fournier’s gangrene per year. Patient race and number of surgeries did not predict mortality risk. †Hospital-related predictors were adjusted for patient age, race, Charlson comorbidity index, and patient admission via transfer. Hospital location, bed size, ownership and US region did not predict mortality risk. |

|||

In a separate model evaluating hospital-associated predictors, mortality was 42–84% lower at hospitals treating more than 1 Fournier’s gangrene case per year (p<0.0001), after adjustments for patient age, race, Charlson comorbidity index, and admission via transfer. Patients at teaching hospitals had higher mortality (aOR 1.9) than those at non-teaching hospitals. However, when the model was adjusted for the number of surgeries, teaching hospital status was not an independent predictor of mortality.

4 Discussion

These population-based epidemiological studies provide a broader perspective than previous studies of Fournier’s gangrene. The major advantage of our population-based approach was the ability to identify a large number of Fournier’s gangrene cases managed at multiple centers, including tertiary care referral hospitals and non-referral hospitals, limiting case-selection and publication biases.

We confirmed that Fournier’s gangrene is indeed rare, representing less than 0.02% of hospital admissions in the US with an overall incidence of 1.6 cases per 100,000 males per year. Most hospitals (66% overall) cared for no patients with Fournier’s gangrene during a given year, and only 1% of hospitals cared for ≥5 cases per year. Thus, even high-volume centers cared for a patient with Fournier’s gangrene every few months.

Overall mortality was 7.5% in our population-based study. This was substantially lower than rates reported in the literature (Table 1). The highest mortality was reported in 1972 by Stone and Martin (88% mortality among 33 patients). More contemporary series report fatality rates in the 20–40% range. In our studies, mortality was highest for transferred patients (12.7%) possibly representing the most acutely ill cases. This is a lower rate than most prior studies and is less than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention population-based mortality rate for Group A streptococcal necrotizing soft tissues infections (24%), suggesting that Fournier’s gangrene is less lethal than other necrotizing soft tissue infections [29].

Increased patient age (aOR 4.0 to 15.0, p<0.0001) proved the strongest independent predictor of mortality. Patients in hospitals that treated more Fournier’s gangrene cases had 42 to 84% lower mortality (p<0.0001) than hospitals treating only 1 case per year. This may reflect more aggressive diagnosis, management, and treatment at more experienced hospitals. Patients admitted via transfer also had a higher independent risk of mortality (aOR 1.9). This may reflect more severe illness among transferred patients, lack of critical care facilities at the transferring hospitals, or delays in management and/or treatment. These findings support the need to increase regionalization of care for patients with Fournier’s gangrene. Because management often requires care from urologic surgeons, general surgeons, intensivists and plastic surgeons, a multidisciplinary approach at facilities with greater experience might improve patient outcomes.

Teaching hospitals cared for the majority of Fournier’s gangrene cases while 30% of non-teaching hospitals treated patients with Fournier’s gangrene (p<0.0001). Patients at teaching hospitals were more acutely ill, required more surgical procedures (especially genital/perineal debridements), more mechanical ventilation and other supportive care. These factors likely account for longer lengths of stay, higher hospital charges, and higher case fatality at teaching hospitals. Patients in teaching hospitals had nearly double the unadjusted mortality rate. We hypothesized that this might reflect differences in the severity, management or supportive care, or that diagnostic criteria for Fournier’s gangrene at teaching hospitals might differ from the criteria at non-teaching hospitals. After adjusting for the number of surgeries a patient required during admission, a marker of disease severity, teaching center status was not an independent predictor of mortality. These observations suggest that higher mortality at teaching hospitals likely reflects a more severely ill population. Patient race and other hospital-related factors assessed (location, size, ownership and US region) did not independently predict mortality.

Deaths tended to occur late during hospitalization. Patients who died had longer lengths of stay and greater hospital. These findings may reflect a more indolent course of Fournier’s gangrene following initial therapy. Deaths might reflect in-hospital complications, but we have no data on these events.

Morbidity from Fournier’s gangrene was high. Similar to other reports, cases in this series often required many operations, especially genital/perineal debridements, orchiectomy, cystostomy and/or colostomy [30], [31], [32], [33]. Overall, 30% of survivors required ongoing care after hospital discharge. Given the rarity (7%) of surgical reconstruction of wounds during the initial hospitalizations, we suspect this ongoing care was necessary to facilitate closure of many patients’ open wounds.

This study has important limitations. Our approach was retrospective using administrative data and subject to the inherent biases of retrospective designs. The database provided no clinical or microbiologic variables to support the diagnosis, determine the degree/severity of infection or percent surface area of skin involvement, or calculate a Fournier’s Gangrene Severity Index [12], [13], [14]. We were unable to examine urethral stricture as a comorbidity because this information was not in the dataset. We could not determine if differential coding of comorbidities occurred, with comorbidities more likely to be captured in the more severely ill patients and in those who died. We may have excluded patients managed with antibiotics only because our case definition required a surgical debridement. However, our subgroup analysis revealed that patients who did not receive a debridement did not merit a diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene. It is also possible that case fatality was inflated slightly because we included all subjects who died with a Fournier’s gangrene diagnosis code, but required survivors to have both a Fournier’s gangrene diagnosis code and a genital/perineal debridement. The number of distinct visits to the operating room could be determined for 61% of cases, potentially limiting this variable as a marker of disease severity. We have limited information on women.

5 Further research

Further information on the instigating factors leading some patients to develop this severe disease is necessary. In addition, the data on the behavior of Fournier’s gangrene in women is limited and it is currently unclear if this seemingly rare subgroup of patients might benefit from differences in management.

6 Conclusions

This is the largest study of Fournier’s gangrene and the first population-based study allowing accurate estimation of incidence and case fatality. Our study provides needed data on the management of this complex condition in the USA. We are aware of no comparable data from other areas. We provide new insights into the rarity and hospital experience with Fournier’s gangrene, regional trends and comorbidities. Our findings agree with prior literature on the age of onset, and comorbid risk factors. However, we found substantially lower mortality than case-series from referral centers. We provide the first comparison of outcomes for patients treated at different hospital types and the first population-based study evaluating predictors of mortality. Our findings support earlier observations from tertiary care referral centers documenting the frequent need for surgical procedures and supportive care.

The large number of cases identified provided a unique opportunity to identify patient-associated and hospital-associated factors predictors or mortality. Fournier’s gangrene patients treated at teaching hospitals required more surgical procedures, more supportive care, longer lengths of stay, greater hospital charges and higher mortality rates, reflecting a more severely ill patient population. Hospitals that treated more Fournier’s gangrene patients had lower mortality rates supporting the need to regionalize care for patients with this rare disease.

Abbreviations key

aOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio

HCUP = Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification

OR = Odds Ratio

SID = State Inpatient Databases

References

[1] Fournier JA. Jean-Alfred Fournier 1832-1914. Gangrène foudroyante de la verge (overwhelming gangrene). Sem Med 1883. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988 Dec;31(12):984-8.[2] Basoglu M, Ozbey I, Atamanalp SS, Yildirgan MI, Aydinli B, Polat O, Ozturk G, Peker K, Onbas O, Oren D. Management of Fournier's gangrene: review of 45 cases. Surg Today. 2007;37(7):558-63. DOI: 10.1007/s00595-006-3391-6

[3] Vick R, Carson CC 3rd. Fournier's disease. Urol Clin North Am. 1999 Nov;26(4):841-9. DOI: 10.1016/S0094-0143(05)70224-X

[4] Eke N. Fournier's gangrene: a review of 1726 cases. Br J Surg. 2000 Jun;87(6):718-28. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01497.x

[5] Endorf FW, Supple KG, Gamelli RL. The evolving characteristics and care of necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Burns. 2005 May;31(3):269-73. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.11.008

[6] Stone HH, Martin JD Jr. Synergistic necrotizing cellulitis. Ann Surg. 1972 May;175(5):702-11. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-197205000-00010

[7] Carvalho JP, Hazan A, Cavalcanti AG, Favorito LA. Relation between the area affected by Fournier's gangrene and the type of reconstructive surgery used. A study with 80 patients. Int Braz J Urol. 2007 Jul-Aug;33(4):510-4. DOI: 10.1590/S1677-55382007000400008

[8] Ayan F, Sunamak O, Paksoy SM, Polat SS, As A, Sakoglu N, Cetinkale O, Sirin F. Fournier's gangrene: a retrospective clinical study on forty-one patients. ANZ J Surg. 2005 Dec;75(12):1055-8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03609.x

[9] Brown DR, Davis NL, Lepawsky M, Cunningham J, Kortbeek J. A multicenter review of the treatment of major truncal necrotizing infections with and without hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Am J Surg. 1994 May;167(5):485-9. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9610(94)90240-2

[10] Pizzorno R, Bonini F, Donelli A, Stubinski R, Medica M, Carmignani G. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of Fournier's disease in 11 male patients. J Urol. 1997 Sep;158(3 Pt 1):837-40. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64331-3

[11] Saffle JR, Morris SE, Edelman L. Fournier's gangrene: management at a regional burn center. J Burn Care Res. 2008 Jan-Feb;29(1):196-203. DOI: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318160daba

[12] Laor E, Palmer LS, Tolia BM, Reid RE, Winter HI. Outcome prediction in patients with Fournier's gangrene. J Urol. 1995 Jul;154(1):89-92. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)67236-7

[13] Yeniyol CO, Suelozgen T, Arslan M, Ayder AR. Fournier's gangrene: experience with 25 patients and use of Fournier's gangrene severity index score. Urology. 2004 Aug;64(2):218-22. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.049

[14] Corcoran AT, Smaldone MC, Gibbons EP, Walsh TJ, Davies BJ. Validation of the Fournier's gangrene severity index in a large contemporary series. J Urol. 2008 Sep;180(3):944-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.021

[15] Kabay S, Yucel M, Yaylak F, Algin MC, Hacioglu A, Kabay B, Muslumanoglu AY. The clinical features of Fournier's gangrene and the predictivity of the Fournier's Gangrene Severity Index on the outcomes. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40(4):997-1004. DOI: 10.1007/s11255-008-9401-4

[16] Lin E, Yang S, Chiu AW, Chow YC, Chen M, Lin WC, Chang HK, Hsu JM, Lo KY, Hsu HH. Is Fournier's gangrene severity index useful for predicting outcome of Fournier's gangrene? Urol Int. 2005;75(2):119-22. DOI: 10.1159/000087164

[17] Tuncel A, Aydin O, Tekdogan U, Nalcacioglu V, Capar Y, Atan A. Fournier's gangrene: Three years of experience with 20 patients and validity of the Fournier's Gangrene Severity Index Score. Eur Urol. 2006 Oct;50(4):838-43. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.030

[18] Unalp HR, Kamer E, Derici H, Atahan K, Balci U, Demirdoven C, Nazli O, Onal MA. Fournier's gangrene: evaluation of 68 patients and analysis of prognostic variables. J Postgrad Med. 2008 Apr-Jun;54(2):102-5. DOI: 10.4103/0022-3859.40775

[19] HCUP Overview. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; January 2018. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/overview.jsp

[20] National Center for Health Statistics. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996.

[21] Sorensen MD, Krieger JN, Rivara FP, Broghammer JA, Klein MB, Mack CD, Wessells H. Fournier's Gangrene: population based epidemiology and outcomes. J Urol. 2009 May;181(5):2120-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.034

[22] Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-83. DOI: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

[23] de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. How to measure comorbidity. a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003 Mar;56(3):221-9. DOI: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00585-1

[24] Gore JL, Lai J, Setodji CM, Litwin MS, Saigal CS; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Mortality increases when radical cystectomy is delayed more than 12 weeks: results from a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare analysis. Cancer. 2009 Mar;115(5):988-96. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.24052

[25] Needham DM, Scales DC, Laupacis A, Pronovost PJ. A systematic review of the Charlson comorbidity index using Canadian administrative databases: a perspective on risk adjustment in critical care research. J Crit Care. 2005 Mar;20(1):12-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.09.007

[26] U.S. Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Population for the United States, Regions, States and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010 (NST-EST2010-01). U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division; 2007. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2010/2010-eval-estimates/nst-est2010-01.xls

[27] US Census Bureau UDoCEaSA. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

[28] Chowdhury PP, Balluz L, Murphy W, Wen XJ, Zhong Y, Okoro C, Bartoli B, Garvin B, Town M, Giles W, Mokdad A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance of certain health behaviors among states and selected local areas--United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007 May;56(4):1-160.

[29] O'Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, Lynfield R, Gershman K, Craig A, Albanese BA, Farley MM, Barrett NL, Spina NL, Beall B, Harrison LH, Reingold A, Van Beneden C; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. The epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infection and potential vaccine implications: United States, 2000-2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct;45(7):853-62. DOI: 10.1086/521264

[30] Hejase MJ, Simonin JE, Bihrle R, Coogan CL. Genital Fournier's gangrene: experience with 38 patients. Urology. 1996 May;47(5):734-9. DOI: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80017-3

[31] Hollabaugh RS Jr, Dmochowski RR, Hickerson WL, Cox CE. Fournier's gangrene: therapeutic impact of hyperbaric oxygen. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998 Jan;101(1):94-100. DOI: 10.1097/00006534-199801000-00016

[32] Laucks SS 2nd. Fournier's gangrene. Surg Clin North Am. 1994 Dec;74(6):1339-52. DOI: 10.1016/S0039-6109(16)46485-6

[33] Yaghan RJ, Al-Jaberi TM, Bani-Hani I. Fournier's gangrene: changing face of the disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Sep;43(9):1300-8. DOI: 10.1007/BF02237442