Itching and burning symptoms in the female urogenital tract

Kurt G. Naber 2

1 Former Head of Section of Gynecological Infections, University Hospital Freiburg, Germany

2 Technical University of Munich, Straubing, Germany

Abstract

The spectrum of the causes of burning pain and itching in the female urogenital tract is broad ranging from harmless vaginal discharge, urinary tract infection, chronic dermatosis to painful primary herpes genitalis, and from the only clinically diagnosable Behçet syndrome to the vulvitis/colpitis caused by A-streptococci, which can lead to a fatal sepsis. Increasing skin damage occurs frequently, which, however, can be avoided by better care. With appropriate experience, most diagnoses can be made based on the clinical picture. The majority of the female patients can be helped quickly if the diagnosis is correct.

1 Summary of recommendations

Although the spectrum of the causes of burning pain and itching in the female urogenital tract is broad, with the appropriate experience, most diagnoses can be made based on the clinical picture and on the complaints of the patients.

- Burning symptoms are more common and are found mainly in infections of the vulva and bladder, in many dermatoses, injuries and skin damages.

- Itching is typical for fungal infections (the only frequent infection with itching), dermatoses (mostly early stages), allergies, skin dryness and the rare parasitic diseases.

- Abdominal pain associated with altered micturition behavior indicates UTI, although disorders of the fallopian tubes and the ovariesy must not be overlooked.

- Increased discharge occurs in many vaginal infections, without further symptoms often with bacterial vaginosis (thin vaginal discharge and odor).

2 Introduction

The patient complains of itching or burning, lower abdominal pain, possibly also increased vaginal discharge and dysuria. Because of the high sensitivity in this area, urogenital complaints are a frequent reason for the doctor's consultation. With the following overview, the authors would like to help the general practitioner to diagnose such complaints differentially and to treat them properly.

The female urogenital tract is not only colonized by a variety of organisms, but is also confronted with sexually transmitted pathogens. Especially due to the proximity to the anus, contamination with enteric microorganisms may occur. Under certain circumstances these may cause infections in the urinary bladder or the internal or external genitalia. Also, this area is stressed mechanically by its biological function and the associated cleaning efforts, which can lead to skin lesions presenting entry sites for bacterial/viral pathogens or fungi.

In addition to infections, inflammatory dermatoses, dysplasia, allergies and increasing skin damage are caused by new trends such as clean intimate area, intimate shave, piercing, etc. With increasing age, decreasing estrogenization leads to tissue atrophy and functional limitations.

3 Diagnostics

Medical history, visual inspection, colposcopy and microscopy of the vaginal fluid as well as urinalysis may allow differentiation between urological or genital problems, infection or dermatosis/atrophy. The microbiologist's help is particularly necessary in case of suspected urinary tract infection (UTI) and special genital pathogens, e.g. A-streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus.

The differential diagnosis of urogenital complaints includes:

- Urethritis and cystitis caused by uropathogens

- Interstitial (abacterial, chronic) cystitis

- Vulvitis and colpitis caused by pathogens

- Inflammatory dermatoses of the vulva

- Allergic reactions of the vulva

- Dysplasia of the vulva

- Skin damage in the urethral area, introitus or anal area

- Atrophic changes of the vagina and vulva

In general, a brief history of a few days is typical for a urogenital infection or for a not too frequent allergic reaction or injury. Chronic complaints, on the other hand, are more typical for inflammatory dermatoses, atrophies, chronic inflammatory processes and skin damages, anatomical features or chronic bladder problems, e.g. interstitial cystitis. It is important to know that some acute infections may become chronic or recurrent, e.g. recurrent cystitis.

The nature of the complaints also leads to differential diagnosis:

- Burning symptoms are more common and are found mainly in infections of the vulva and bladder, in many dermatoses, injuries and skin damages.

- Itching is typical for fungal infections (the only frequent infection with itching), dermatoses (mostly early stages), allergies, skin dryness and the rare parasitic diseases.

- Abdominal pain associated with altered micturition behavior indicates UTI, although disorders of the fallopian tubes and the ovaries must not be overlooked.

- Increased discharge occurs in many vaginal infections, without further symptoms often with bacterial vaginosis (thin vaginal discharge and odor).

| Causes of itching | Causes of burning complaints |

| Infections | |

|

|

| Inflammatory, non-inflammatory dermatoses | |

|

|

| Skin lesions/others | |

|

|

Diagnostic steps

Anamnesis and examination in case of itching in the genital area:

- Duration of itching? Acute: 1–2 weeks; chronic: for months

- Is the skin altered: redness, white coloring, coarsening lesions?

- Additional complaints such as vaginal discharge, inclusion of other body sites?

- Clinical inspection of skin (if possible with vulvoscopy/colposcopy) and vaginal discharge

- Native microscopy of the vaginal fluid for fungal elements and leukocytes

- Smear for microbiology for the exclusion/detection of fungi

Anamnesis and examination for genital burning:

- Acute event, pain with lesions on the skin?

- Chronic burning with redness, diffuse or sharply defined, vaginal discharge?

- Chronic burning and contact pain with apparently normal genitalia?

- Clinical inspection of skin (if possible with colposcopy) and vaginal discharge

- Native microscopy for moving trichomonads and number of granulocytes

- Smear for microbiology, if no trichomonads

Anamnesis for burning during micturition (dysuria):

- Dysuria, frequency, nocturia and urgency?

- Incontinence?

- Hematuria?

- Suprapubic pain?

- Vaginal discharge, vaginal irritation?

- Preceding urinary tract infections?

- Fever, flank pain?

Ambulatory examination:

- General clinical examination of vulva, urethral opening and anal area

- Gynecological examination with speculum adjustment and colposcopy of vagina and portio with assessment of the vaginal fluid by means of pH value, possibly amintest, in case of suspected dysplasia vinegar test of vulva and portio (colposcopy)

- Native microscopy of the vaginal fluid after dilution with 0.1% methylene blue solution

- In the case of suspected UTI: urine examination in practice (midstream), odor, turbidity, dip stick test (granulocytes, erythrocytes, protein, glucose, nitrite)

- Microscopy of fresh urine with 400-fold magnification

Diagnostic laboratory tests:

- Pathogen detection by culture (urine, smear), PCR, serology, etc.

- Histology of a tissue sample

- Inflammatory parameters (leukocytes in the blood, PCR) in the case of general symptoms (debility, limb pain or even fever)

Infections of the vagina always have a markedly increased number of granulocytes in the vaginal fluid, which can be detected quickly by microscopy at 400-fold magnification in a wet or native preparation. Three times more epithelial cells than granulocytes in the vaginal fluid speak is against infection-induced inflammation. If trichomonas or pseudomycellia (fungal threads) tumbling through the wet preparation are not observed by microscopy with a 40-objective lens besides an increased number of granulocytes, a swab for microbiological investigation has to be performed (see Table 2).

| Normal vaginal flora | Lactobacilli in high concentration; Enteric bacteria in small numbers (only culturally recognizable), pH 4.0 (by lactobacilli), Epithelia 3–10 times more frequent than leukocytes |

| Disturbed vaginal flora | Mixed flora: little lactobacilli, many enteric bacteria, Epithelia 3–10 times more frequent than granulocytes |

| Aminvaginose/BV | No/hardly lactobacilli, vast number of small bacteria, Clue Cells pH 4.5–5.5, epithelia 3–10 more frequent than granulocytes |

| Colpitis | Vaginal wall reddened, yellow fluor vaginalis, firm in case of fungi, otherwise thin, pH 4.0–5.5, depending on lactobacilli amount, granulocyten 3–30 times more frequent than epithelia |

| Cystitis | ≥3 granulocytes per field in fresh urine at 400-fold magnification |

Dermatoses also show inflammation, but the vaginal fluid is normal. The inflammation takes place in the skin and is detectable only histologically.

Diseases with itching

Fungal infections

Candidosis is one of the most common causes of itching in the genital area. It can be the sole cause of itching, but it can also be an additional component. Fungal infections should therefore always be excluded in case of itching, since treatment is possible.

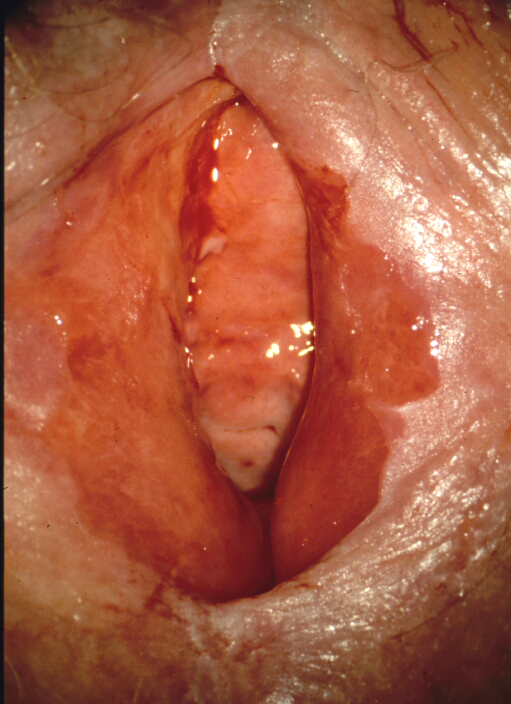

The clinical picture of a fungal infection can differ considerably. Usually redness is more or less intense, occasionally also a slight swelling, usually a fluffy, yellowish vaginal discharge is present (Figure 1). Microscopically almost always fungal elements and granulocytes can be seen if appropriate samples are taken. Pseudomycelium is almost always proof of an infection by Candida albicans, the most common and most important causative agent of genital fungal infection. A culture is necessary when symptoms are present, but no fungi are seen, or if only small germinating cells (e.g. C. glabrata) or large elongated germinating cells (indicating Saccharomyces cerevisiae = baker's yeast) are found in recurrent or chronic courses.

Not every fungal involvement, nor each colonization of Candida albicans causes inflammation and thus discomfort. A therapy is only indicated in case of complaints or during pregnancy.

Many substances and galenic forms are available for the treatment of candidiasis. Occasional candidiasis should be treated locally, chronic recurrent candidiasis with severe infestation of the vulva should be treated orally with, for example, fluconazole (150 mg once or in severe cases 2 to 3 times every other day). Symptoms should disappear after therapy, for example on the 4th to 6th day. If this is not the case, the fungus is not the cause of the discomfort or just an additional disease. Therapy of the partner is recommended for chronic recurrent candidiasis. Regular skin care leads in the long term to an epithelial improvement and thus to reduction of pathogens from the skin. A biopsy should be performed if the skin alterations persist despite optimal therapy.

Parasites

Scabies (mites), phthiriasis (felted lice) and worms (oxyurans) can also be a cause of itching, although rarely.

Dermatoses and skin damage

Patients with itching are problematic if no abnormalities can be seen and fungal infection is culturally excluded. In this case bacterial cultures are almost no help. The authors are not aware of any bacterial infection associated with itching. On the contrary, bacteriological results tend to create confusion, since they are infrequently treated unnecessarily with antibiotics.

Apart from rare parasitic diseases, itching is mainly caused by non-infective dermatoses and skin damages. Dermatoses in early stage may be curable, when treated properly.

Lichen sclerosus

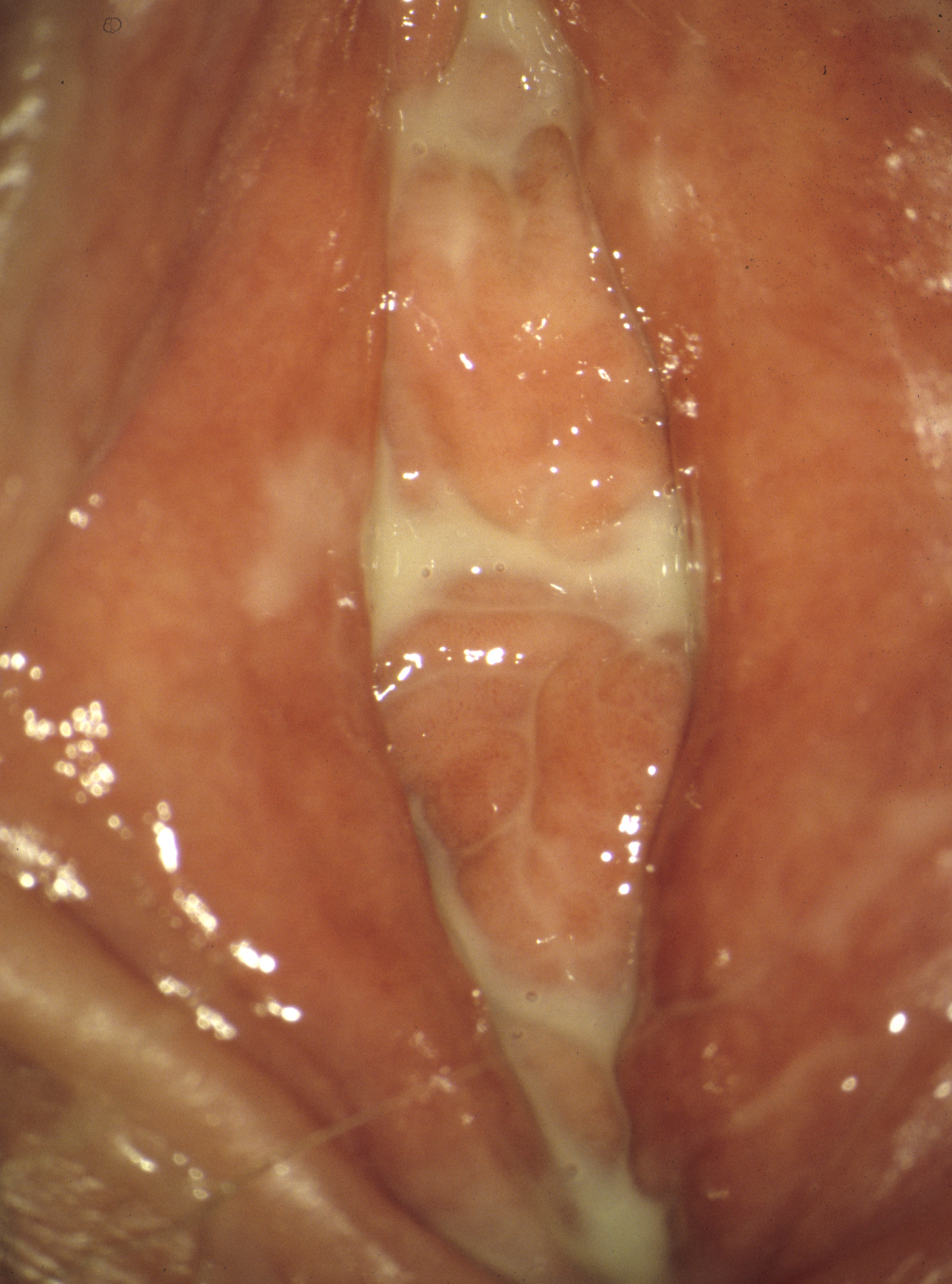

This is the most common itchy, inflammatory, non-infective dermatosis of the vulva and does not occur just in older age, but also in young girls (Figure 2). The diagnosis of the early stage is particularly important in young women. Occasionally, only effects of scratching, like slight hemorrhages and skin damages are visible.

Typical early signs are the persistent itching, which occasionally may not exist, and the whitish alterations on the small labia. The constrictions of the clitoris and later on the introitus are a very typical sign of a lichen sclerosus (Figure 3). Co-involvement of the area around the urethral opening is rather rare. A biopsy is necessary only in the early stage or in the absence of clinical experience.

Figure 3: Lichen sclerosus in a 36-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

The recommended therapy today consists mainly of corticosteroid ointments. In the beginning highly effective corticosteroids, e.g. clobetasol, are preferred. Since it is a chronic disease, repeated treatments are almost always necessary. For this purpose, less atrophic corticosteroids, for example clobetasol, may also be used. Often, in the early stage an interval therapy for 1 to 2 weeks is sufficient. Regular, multi-day care with greasy ointments is essential and saves corticosteroids. Testosterone has been obsolete for years. The immune modulators tacrolimus and pimecrolimus do not cause atrophy, but are less effective.

Lichen planus of the vulva

Its diagnosis on the vulva is difficult, since it is less frequent than the lichen sclerosus and its clinical picture is scarcely known. Lesions are white, reticular structures, which are almost recognizable only by colposcopy. This stage occurs many years before the better known late form, the Lichen planus erosivus, which is also called lichen ruber in the German-speaking world. At this stage, synechiae of the introitus are also possible with displacement of the urethral opening (Figure 4). The genital lichen planus is mostly accompanied by involvement of the oral cavity, facilitating the diagnosis. Otherwise, the diagnosis can be confirmed histologically. By early therapy (corticosteroid ointments), corresponding approximately to that of lichen sclerosus, the late stage can be largely avoided.

Figure 4: Lichen planus erosivus in a 50-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

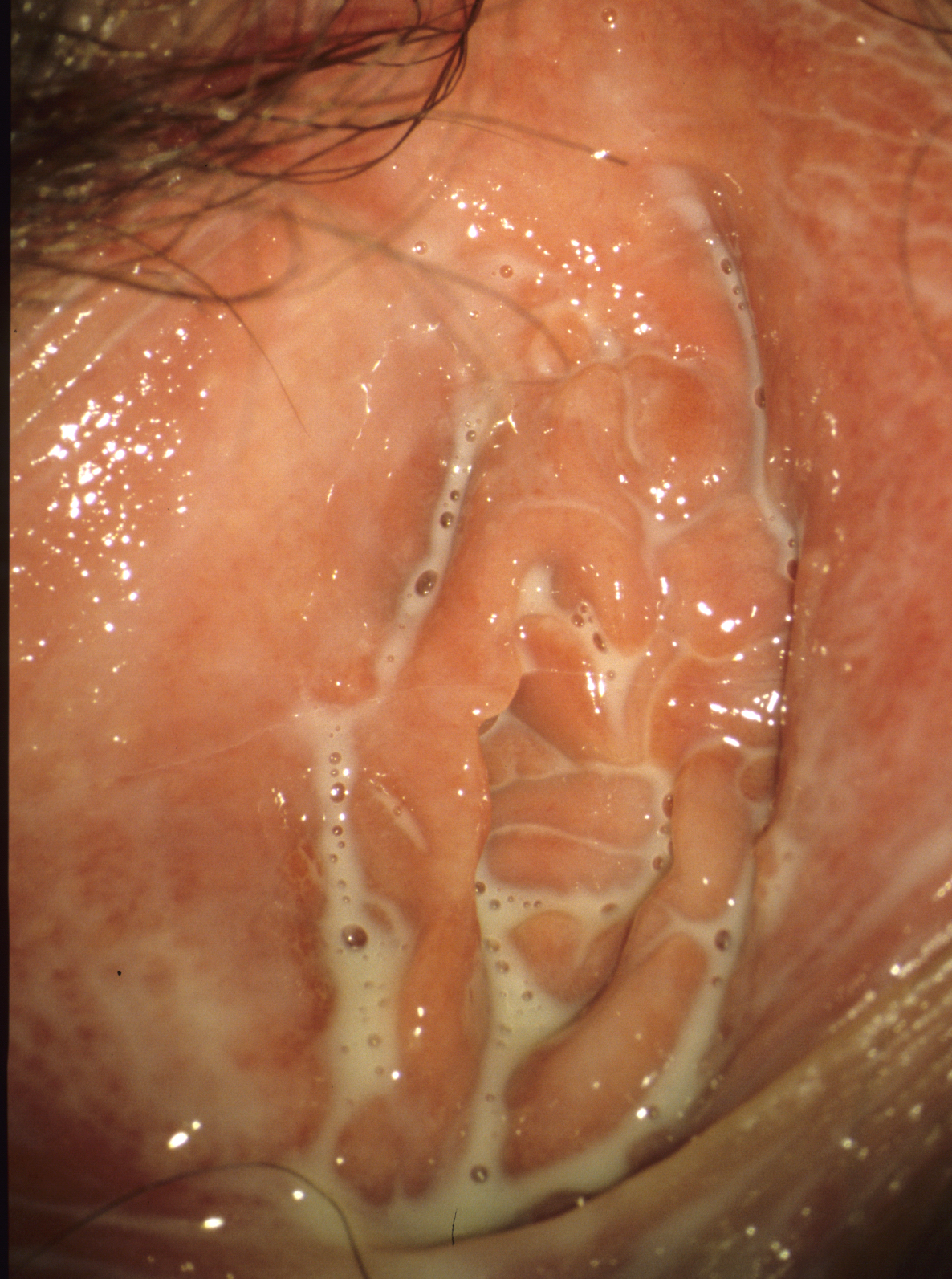

Lichen simplex chronicus of the vulva

This is not only an immune disease, like the other two kinds of lichen, but rather a consequence of scratching. It frequently starts with candidiasis and is precipitated by a genetic disposition. Clinically, there is an epithelial coarsening, occasionally also redness, often only one-sided (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Lichen simplex chronicus in a 42-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

Healing is achieved by omission of scratching and rubbing and consistent skin care with well tolerated fat containing ointments. Initial short-term use of a corticosteroid ointment (one week) is helpful, since this results in a faster therapeutic success, which is also psychologically important. However, it does not eliminate the need for long-term skin care and omission of mechanical overstraining.

Burning complaints

Urinary tract infections

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are caused by a bacterial invasion of the urinary tract. The most common pathogen in community-acquired UTI is E. coli (>70%), rarely Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Staphylococci and enterococci. Typical complaints of uncomplicated cystitis, found frequently in women, are burning during urination (dysuria) and imperative urge to urinate (urgency). Suprapubic pain and nocturia are frequent symptoms. Flank pain, costovertebral angel tenderness or fever do not occur. If present, these symptoms indicate pyelonephritis.

In the case of a typical clinical presentation (dysuria, pollakisuria), corresponding urine findings and lack of vaginal discharge, uncomplicated cystitis can be diagnosed with such certainty that further investigations are unnecessary and treatment can be carried out.

Genital viral infections

The primary genital herpes is the most severe and painful infection that a young woman can have. The whole vulva is swollen and covered with multiple lesions at different stages (Figure 6). A sexual contact has taken place in the last 3 to 6 days. The diagnosis is made according to the clinical picture and the swollen and painful inguinal lymph nodes. With the immediate oral acyclovir treatment (200 mg 5 times daily for 5–8 days) a rapid improvement can be achieved.

Figure 6: Primary herpes genitalis in a 26-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

In contrast, the recurrent herpes genitalis is much milder and only occurs in one place. It becomes a problem if it relapses very frequently. Here as well, oral acyclovir therapy over 1–2 days is most effective.

Genital bacterial infections

The most dangerous vulvitis with burning pain is caused by A-streptococci (Figure 7), as this pathogen can ascend and cause even fatal sepsis. It is recognized by the redness of the vulva and vagina, and the thin, yellow, granulocyte-rich vaginal discharge. The diagnosis can only be made by the proof of A-streptococci. Therefore a swab for culture has to be sent to the microbiologist in every vulvitis/colpitis unless recognizable pathogens (trichomonas or fungi) are seen immediately.

Figure 7: A-streptococcal vulvitis in a 39-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

The clinical picture may be identical in case of the more likely chronic and unfortunately occasional recurrent vulvitis/colpitis plasmacellularis. If only enterobacteria are detected in the culture, this diagnosis becomes probable. With local clindamycin treatment cure can be achieved in >90% of the cases.

Trichomoniasis (Figure 8), which has become rare in the meantime, is more likely a problem of discharge than of pain. It is detected microscopically on the wet preparation (without methylene blue) by the moving trichomonas. Elimination can be achieved quickly by oral administration of 2 g of metronidazole. Therapy of the partner is obligatory.

Figure 8: Trichomoniasis in a 24-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

Bacterial vaginosis (BV)/aminvaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common vaginal disorder in women of childbearing age. It is irritating due to an increased vaginal discharge with a fishy odor (amines of the anaerobes). It is a mis-colonization with typical bacteria characterized by a loss of lactobacilli – especially those producing hydrogen peroxide – as well as by a sharp increase of anaerobic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis and other anaerobic Gram-negative rods. BV is associated with clinical risks such as premature birth or inflammation in the pelvic area. Their high recurrence rate also has a negative impact on many women’s quality of life. Together with the appearance of so-called key cells (clue cells) in the native preparation, the diagnosis can be made relatively easy. The therapy ranges from acidification via antiseptics, e.g. dequalinium chloride, to antibiotics such as metronidazole or clindamycin.

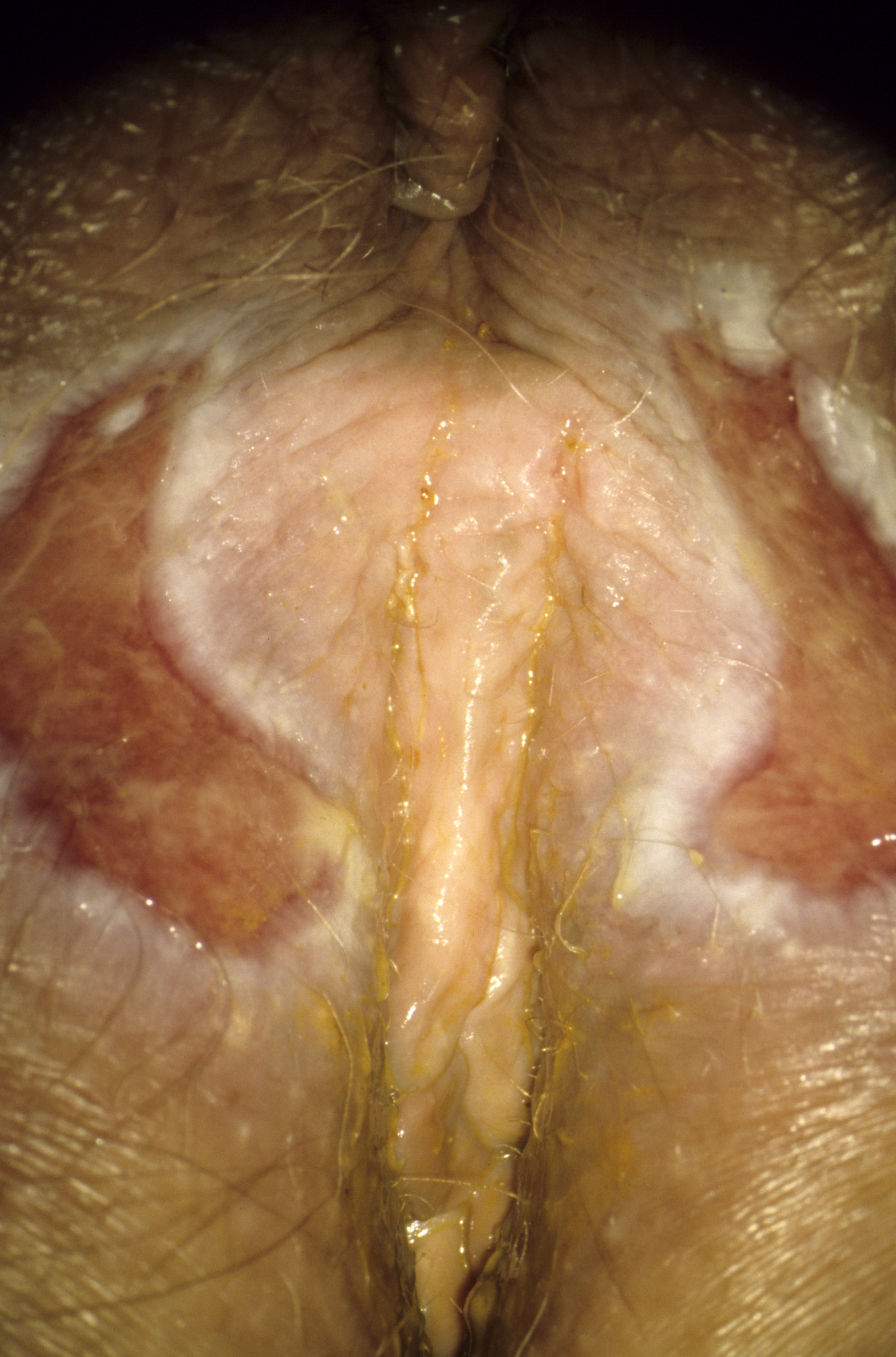

Atrophic diseases

With increasing age declining estrogen levels cause atrophy in the urogenital region, which can lead to a variety of symptoms. The skin is thinner, more sensitive and vulnerable due to smaller epithelial cells. This causes an increased susceptibility to urinary tract infections, dyspareunia and skin injuries (Figure 9). Atrophy can also occur in adolescent women with low estrogen receptor density or low-dose ovulation inhibitors.

Figure 9: Atrophia with bleeding into the urethral opening in a 60-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

The local administration of estrogens, mainly estriol, is a remedy, small amounts being often sufficient.

Further causes of burning symptoms

Behçet's syndrome

The Behçet syndrome is acute and extremely painful. It is an immune arteritis causing deep ulcers (Figure 10) or to many small ulcers (Figure 11). Other than in primary genital herpes, the inguinal lymph nodes are not swollen. The diagnosis is made solely from the clinical picture and the clinical course or from the faster healing by a corticosteroid ointment. Unfortunately, it is often not diagnosed until very late or not at all.

Figure 10: Behçet syndrome, large solitary ulcer in a 18-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

Figure 11: Behçet syndrome with multiple ulcers in a 21-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

Fixed drug exanthema

An acute painful vulvitis can also be triggered by a fixed drug exanthema. There is a sudden painful swelling of the small labia, without a mechanical strain or visible lesions. The diagnosis is made by histology and/or history (considering certain therapeutics such as cotrimoxazole, doxycycline or others). Quick cure can be achieved by a corticosteroid treatment.

Injuries

In the meantime the most common causes of pain in the vulvar region are injuries. They can be so extreme that they mimic a severe dermatosis or even a malignancy (Figure 12), or so discreet that they can only be detected by colposcopy. Cause is always a skin strength reduced by atrophy or dryness and an increased mechanical strain caused by cleaning measures or sexual intercourse. Here, only a skin improvement by, for example, estrogen or skin care with fat containing ointments helps against mechanical stress.

Figure 12: Severe skin lesions because of constant washing with anal incontinence (© Eiko Petersen)

Dysplasia

Primary stages of vulvar cancer, VIN (Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia) or early Bowen disease can also cause discomfort, especially if they are extended as in Figure 13. Suspicious persisting alterations therefore have always to be biopsied.

Figure 13: Morbus Bowen in a 61-year-old women (© Eiko Petersen)

4 Conclusions

The spectrum of the causes of burning pain and itching in the female urogenital tract is broad. With the appropriate experience, most diagnoses can be made based on the clinical picture. The majority of the female patients can be helped quickly if the diagnosis is correct.

5 Acknowledgement

Unfortunately Eiko E. Petersen has died 10 May 2016. The corresponding author is thankful to Dr. Dagmar Petersen to give permission to use the copyrighted fotos in this article only to be published posthum of the first author.

References

[1] Farage MA, Galask RP. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: A review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005 Nov;123(1):9–16. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.05.004[2] Lotery HE, McClure N, Galask RP. Vulvodynia. Lancet. 2004 Mar;363(9414):1058–60. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15842-X

[3] Petersen EE, editor. Farbatlas der Vulvaerkankungen [Diseases of the vulva]. 3rd ed. Freiburg: Kaymogyn; 2013.

[4] Petersen EE, editor. Infektionen in Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [Infections in gynecology and obstetrics]. 5th ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2011.

[5] Petersen EE. Frauen mit chronischen Vulvabeschwerden: Schwierige Frauen oder nur schwierige Diagnose? [Women with chronic vulvar complaints]. Frauenarzt 2012;53:246-252. Available from: http://www.ag-cpc.de/media/2012-03-Petersen.pdf

[6] Pirotta MV, Garland SM. Genital Candida Species Detected in Samples from Women in Melbourne, Australia, before and after Treatment with Antibiotics. J Clin Microbiol. 2006 Sep 1;44(9):3213–7. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.00218-06

[7] Schöfer H, Bruns R, Effendy I, Hartmann M, Jappe U, Plettenberg A, Reimann H, Seifert H, Shah P, Sunderkötter C, Weberschock T, Wichelhaus TA, Nast A; German Society of Dermatology (DDG)/Professional Association of German Dermatologists (BVDD); Infectious Diseases Society of Germany (DGI); German Society for Hygiene and Microbiology (DGHM); German Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases (DGPI); Paul Ehrlich Society for Chemotherapy (PEG). Diagnosis and treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections of the skin and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011 Nov;9(11):953-67. DOI: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07786.x

[8] Wagenlehner FM, Hoyme U, Kaase M, Fünfstück R, Naber KG, Schmiemann G. Uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011 Jun;108(24):415-23. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0415