The relation between teaching-related self-efficacy and general job-related well-being – a cross-sectional study among young physicians

Benjamin Kiver 1Pascal O. Berberat 1

Martin Gartmeier 1

1 TUM MEC, TUM School of Medicine and Health, Technical University of Munich, Chair of Medical Didactics, Medical Teaching Development and Educational Research, Munich, Germany

Abstract

Objective: The development of didactic skills plays a relatively subordinate role in medical training. However, teaching makes a central contribution to the training of young physicians and is an important part of the profession. In the present study, we therefore examine the question of how physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy is related to aspects of their general job-related well-being. This construct is measured via the three components job satisfaction, job motivation and emotional exhaustion. From the results, we derive starting points for measures to increase the teaching-related self-efficacy of lecturers and the quality of teaching in clinical settings in the future.

Method: Between 10/2016 and 09/2018, participants in university didactics training courses for medical lecturers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) University Hospital were surveyed in writing. On this basis, we were able to analyze data from 293 participating physicians. We examined the assumed connections between teaching-related self-efficacy and emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and job motivation using Pearson correlations. For the relation to teaching experience, we calculated a Spearman correlation. We examined by t-test a possible difference in teaching-related self-efficacy between physicians who had received didactic training prior to our training vs. those who had not.

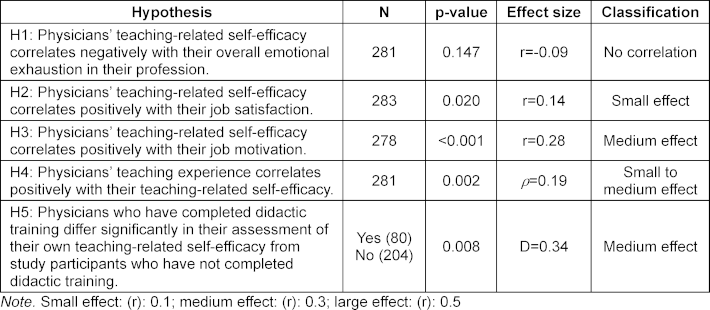

Results: The study showed a statistically significant correlation between teaching-related self-efficacy and job satisfaction (r=0.138; p=0.020) as well as with job motivation (r=0.278; p<0.001). There was no statistically significant correlation with emotional exhaustion (r=-0.087; p=0.147) at work. Furthermore, teaching experience correlated positively with teaching-related self-efficacy (ρ=0.186; p=0.002) and physicians rated themselves significantly more self-efficacious in teaching if they had previously completed didactics training (t(282)=2.684, p=0.008).

Conclusion: The teaching-related self-efficacy of physicians teaching at university correlated closely with the aspects of job satisfaction and job motivation, but not with emotional exhaustion. These findings offer starting points for interventional studies to investigate causal relationships that foster approaches to promote physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy.

Keywords

self-efficacy in teaching, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, job motivation, general job-related well-being, teaching experience

1. Introduction

In addition to patient care, research and teaching are among the core responsibilities of physicians working at a university hospital. Given the limited financial and time resources, doing justice to all three areas of responsibility represents a particular challenge. Where research is concerned, there are structurally better opportunities to expand staff resources, e.g., by acquiring third-party funding or taking time off to conduct studies. By contrast, a high level of commitment to teaching is usually neither particularly encouraged nor rewarded. In consequence, physicians often lack the necessary time and incentives to set themselves ambitious didactic goals [1]. This relative neglect of teaching has negative effects, including on students, who often find the teaching they receive to be unsatisfactory [1]. Moreover, since the training of didactic skills does not play a role in medical studies[2], many physicians feel inadequately prepared when they are asked to design courses as part of their first employment at a university hospital [3]. However, since good teaching is a decisive factor in the quality of training for capable physicians, their didactic competence is of great importance for the entire medical profession. One question that has so far been neglected in this context is what role teaching competence plays in the job-related well-being of young physicians, who often find themselves thrust into the role of teachers, with little previous experience and medical didactic expertise. This might contribute to them feeling overwhelmed or out of place, and their job-related well-being could suffer as a result.

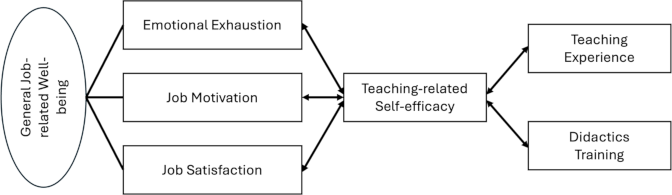

Our study builds on existing research on the cognitive characteristics of teachers, which from a theoretical perspective are more directly relevant to medical teaching [4]. Specifically, we shed light on a possible relationship between physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy and aspects of their general job-related well-being, which we operationalize in the present study through the aspects of emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and job motivation. In addition, we examine the relation of teaching-related self-efficacy with teaching experience and with the completion of medical didactic training or further education in the past. The postulated associations are highly relevant, as higher job-related well-being itself is associated with positive job-related factors, such as performance or health [5], [6]. Therefore, a positive association between teaching-related self-efficacy and positive general work factors is evident. The results of our study contribute to understanding the importance of physicians’ didactic skills in general and in particular regarding the individual well-being of physicians. The theoretical concepts central to this article and their relation to each other are presented in more detail below (see figure 1 [Fig. 1]). All hypotheses were only formulated after data collection, rendering the analyses exploratory.

Figure 1: Hypothetical correlation between variables and structure of the construct of well-being

1.1. Teaching-related self-efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their own resources for coping effectively with certain challenges and tasks. The concept was coined by Bandura [7] and is the subject of widespread and ongoing research today. According to Lent and Brown [8], self-efficacy lays the foundation for well-being, personal success, and motivation. In addition to global self-efficacy, it is assumed that domain- or task-specific self-efficacy, such as teaching-related self-efficacy, also exist [9]. Teaching-related self-efficacy refers to the assessment of one’s own abilities to design didactic measures that best support students in achieving specific learning goals [10], [11].

Klassen and Chiu [12] found a positive correlation between teachers’ self-efficacy regarding their own teaching and their job satisfaction. In addition, teachers with higher self-efficacy showed lower stress levels [13]. High teaching-related self-efficacy also appears to have a positive effect on learners: In a study of 103 primary school teachers and their 2,148 pupils, a positive correlation between teaching-related self-efficacy and academic performance was demonstrated [14]. These findings underpin the relevance of teachers’ own teaching-related self-efficacy, which has also previously been highlighted in the context of medical didactic research.

In the context of medical didactics, the focus of research to date has primarily been on the self-efficacy of medical students. Wu et al. [15] were able to show that higher intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is associated with increased self-efficacy. It has also been shown that self-efficacy is a variable critical to the learning process for medical students [16]. With regard to teaching-related self-efficacy in particular, Tipwong et al. found in a study of 227 physicians that teaching-related self-efficacy is a significant predictor of professional self-realization and is also negatively correlated to the risk of burnout [17]. In addition, a positive correlation between job satisfaction and teaching-related self-efficacy has been found for physicians [18]. Overall, it is clear that teaching-related self-efficacy is a relevant variable with regard to the quality of medical teaching. To date, however, there has been little research in the context of German university hospitals on the relationship between physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy and intrapersonal characteristics.

1.2. General job-related well-being

The focus of this study is on general job-related well-being, which we operationalize using three variables that are elucidated below. In our study, general job-related well-being is represented by the variables emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and job motivation [19].

1.2.1. Emotional exhaustion

The COVID-19 pandemic increased public awareness of the emotional exhaustion suffered by physicians and nursing staff [20]. Emotional exhaustion refers to a chronic state of physical and mental exhaustion caused by the continuous high or very high demands of work [21], [22] or study [23]. Emotional exhaustion plays a special role in medicine – though not yet in medical didactics – as this field is characterized by high social expectation and a high work intensity (at university hospitals not least due to teaching obligations). Doctors are a vulnerable group in terms of emotional exhaustion. This is confirmed by a Canadian study of 131 doctors, 80% of whom described symptoms of moderate to severe emotional exhaustion [24]. This is relevant because emotional exhaustion exacerbates the likelihood burnout [25], and is negatively associated with job performance [26]. In a study of 508 teachers, teaching-related self-efficacy was found to be the strongest negative predictor of emotional stress [27]. In a Thai study of 227 teaching physicians, teaching-related self-efficacy was shown to be a statistically significant negative predictor of burnout. Based on this, we assume the following hypothesis for the present study:

H1: Physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy correlates negatively with their overall emotional exhaustion.

1.2.2. Job satisfaction

Teaching-related self-efficacy also plays an important role in job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is a multidimensional psychological construct. It is defined as positive emotions that are triggered in an individual by their work or professional experiences [28], [29]. Job satisfaction is critical, not only in terms of job performance [30], but health [31]. The relation between teaching-related self-efficacy and job satisfaction has been widely researched and correlations have been confirmed in numerous studies for different occupational groups [32], [33], [34]. Buric and Moe [35], for example, found a significant relationship between teaching-related self-efficacy and job satisfaction in their study of 1214 teachers [18]. We build on this with the following hypothesis:

H2: Physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy of correlates positively with their job satisfaction.

1.2.3. Job motivation

In order to create a working environment in which doctors can consistently perform at a high level, understanding their motivation is crucial [36], [37]. Job motivation correlates with health [38], while self-efficacy in turn is an important factor influencing job motivation [39], [40]. Demir [41] found in a study of teachers that an increase in their self-efficacy was associated with increased work motivation. However, the association of teaching-related self-efficacy with job motivation has not yet been confirmed in the field of medical didactics. We therefore put forward the following hypothesis:

H3: Physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy correlates positively with their job motivation.

1.3. Teaching experience

Another potentially relevant factor influencing teaching-related self-efficacy is the extent of relevant experience in university teaching [42]. In a study by Gale et al. (2021), 67% of the participants surveyed cited positive teaching experience as a cause of increased teaching-related self-efficacy [43]. In their study of experienced and inexperienced teachers, Tschannen-Moran and Hoy [10] were able to show that experienced teachers rated themselves as significantly more self-efficacious. Applied to the clinical sector, we therefore assume the following hypothesis:

H4: Physicians’ teaching experience correlates positively with their teaching-related self-efficacy.

1.4. Didactics training

A further aim of this study is to investigate whether the completion of higher education didactics training is associated with a higher teaching-related self-efficacy assessment by physicians themselves. Typical elements of such training courses are in-depth discussions of teaching-learning theories and modern approaches to higher education didactics, structured and focused testing of current teaching-learning methods, and supervision of one’s own teaching activities with feedback. These elements can help to promote didactic skills. We therefore see university didactics training as a useful prerequisite for increasing teaching-related self-efficacy assessment.

The benefits of interpersonal skills training (and we consider didactic action as such) are well documented, including for the medical profession. Ammentorp et al. [44] found that clinical and nursing staff were able to increase their self-efficacy in terms of communication by an average of 37% with five days of communication training. In a meta-analysis by Mata et al. [45], the positive effect of various communication training courses on the self-efficacy of physicians was confirmed. The benefits of specialized didactics training for university teaching have also been confirmed in numerous studies. In his study, Tzivinikou [46] showed that didactics training for teachers significantly increased their teaching-related self-efficacy. Based on these correlations, we postulate the following hypothesis:

H5: Physicians who have completed didactic training differ significantly in their assessment of their own teaching-related self-efficacy from study participants who have not completed didactic training.

2. Methods

To investigate the hypotheses formulated above, we use data from the scientific monitoring of a university didactic training program for medical lecturers conducted between 10/2016 and 09/2018 using standardized questionnaires. All new employees with teaching duties at the TUM University Hospital are required to complete a lecturer training course within their first year. The lecturer training takes place in the form of lectures, discussions, and group work on various didactic topics and is supervised by members of the chair of medical didactics. The participants are therefore predominantly young professionals at the start of their careers, although all employees with teaching duties are free to particpate in the training on a voluntary basis.

As part of the training, we informed all participants about the study and asked them to complete the questionnaire. Participation in the study was voluntary; if participants decided not to take part, this had no negative consequences for them. Our study was a cross-sectional. The underlying data was collected at 13 points in time as part of the presence-based training. In addition, an e-mail was sent out from the TUM University Hospital to recruit additional doctors online. It is therefore not possible to state the maximum number of participants that could be recruited or the response rate. A total of 315 people took part in the study, with data from 293 trial participants included in the analyses. 22 people were excluded as they were not physicians.

2.1. Instruments of measure

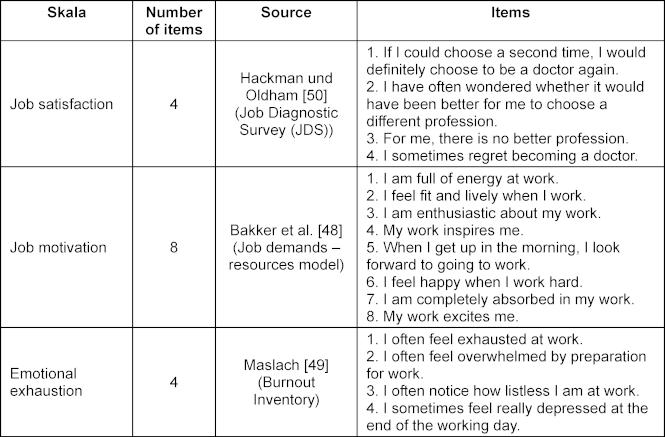

Established questionnaires on perceived self-efficacy in teaching, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and job motivation were used to record the variables in the focus of the study (see table 1 [Tab. 1]). A four-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” was used for all instruments of measure. Perceived self-efficacy in teaching was assessed using items after Pfitzner et al. [47], with some adaptations. The scale showed good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75. To measure job motivation, we used the eight-item scale derived from Bakker et al. [48], which also showed good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. The four items on emotional exhaustion were adapted from Maslach [49]; the scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82. The job satisfaction scale comprised four items and was developed by Hackman and Oldham [50]; it had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85. If all constructs operationalized here as partial aspects of general job-related well-being (i.e., the items of the emotional exhaustion (inverted), job satisfaction and job motivation scales) are combined, the scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Participants were asked about their teaching experience in four categories: up to one year, 2-5 years, >5-10 years, and over 10 years of teaching experience. Participation in teaching didactics training of any kind prior to our training was also recorded with a dichotomous yes/no item.

2.2. Statistical analyses

The analyses were based on a significance level of p=0.05. Pearson correlations were calculated to test the first three hypotheses; the fourth hypothesis was tested using a Spearman correlation. A t-test was used to test the fifth hypothesis. All analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS 28 software. No power analysis was performed in advance. To analyze the missing items, we performed a data missing completely at random test (MCAR test) after Little. This resulted in a χ2 value of 489.882 with df=465 and a p=0.205. Since the p>0.05, we cannot reject the null hypothesis. This indicates that the missing values are missing completely at random. Finally, the missing values were eliminated by mean imputation. In the statistical tests, pairwise case exclusion was used when all items of a scale of one of the correlating variables were missing.

2.3. Ethical approval

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of TUM University Hospital (Klinikum Rechts der Isar) (reference 487/19 S-KK).

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

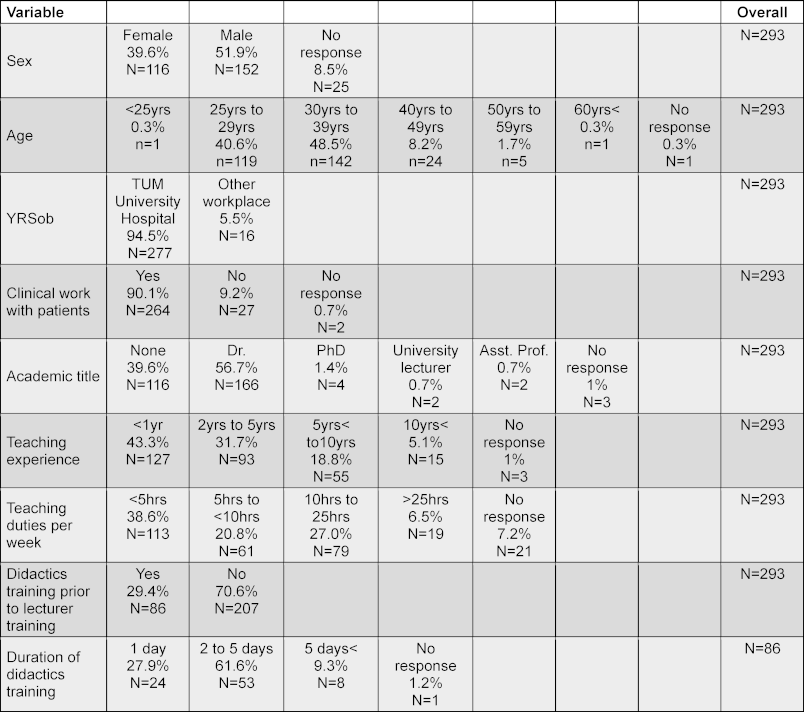

The majority of participants (94.5%) were employees at the TUM University Hospital (Rechts der Isar). The participants were predominantly male, between 25 and 39 years old and had already obtained a doctorate. The majority of participants also had less than one year of teaching experience and had not previously completed any didactics training. Our sample was a conveniance sample with 315 participants. The detailed characterization of the sample, including the missing values, can be found in table 2 [Tab. 2].

3.2. Emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, job motivation

On average, the doctors surveyed in the study were not especially emotionally exhausted (M=2.93, SD=0.70, N=288; recoded scale with maximum (4=not emotionally exhausted at all). Nevertheless, 61 people (21%) still reported themselves emotionally burdened to a relevant extent (48 people over 1 standard deviation below the mean, 13 people over 2 standard deviations below the mean). Contrary to the postulate in hypothesis 1, there was no significant correlation (r=-0.087; p=0.147; N=281) between the teaching-related self-efficacy of physicians and their emotional exhaustion at work. The questionnaire showed that the doctors surveyed were satisfied with their profession (M=3.05, SD=0.80) and motivated in their work (M=2.89, SD=0.54). Higher teaching-related self-efficacy among physicians correlated positively with their job satisfaction (r=0.138; p=0.020; N=283), and it also correlated significantly positively with the respondents' job motivation (r=0.278; p<0.001; N=278).

3.3. The role of teaching experience and skills training

With regard to the extent of teaching experience, there were differences in the various age categories. While physicians with up to one year of teaching experience rated their self-efficacy in teaching on average at M=2.81, SD=0.34, physicians with 2-5 years (M=2.93, SD=0.36), 5-10 years (M=2.98, SD=0.34) and over 10 years (M=2.91, SD=0.22) of teaching experience rated their self-efficacy higher. An analysis of variance of the individual response categories of teaching experience and teaching-related self-efficacy as the dependent variable produced a significant result (F(3, 277)=4.003, p=0.008). A post-hoc Tukey HSD test revealed a significant difference in teaching-related self-efficacy between the group with up to one year of teaching experience and the group with 5 to 10 years of teaching experience. As postulated in Hypothesis 4, teaching experience showed a significant correlation (ρ=0.186; p=0.002; N=281) with the teaching-related self-efficacy of physicians.

The majority of physicians in our sample had not yet completed any didactics training (204 vs. 78 people). Regardless of whether they had completed such training, the doctors in our study tended to rate themselves highly in terms of their own self-efficacy in teaching; nevertheless, there was a difference in favor of those doctors who had already completed didactics training. They rated themselves significantly more self-efficacious (t(282)=2.684, p=0.008) in teaching (M=2.96, SD=0.32) than the comparison group who had not previously attended such training (M=2.84, SD=0.35).

Overall, the significant results in our study showed small to medium effect sizes (see table 3 [Tab. 3]).

Table 3: Overview of study results with effect sizes

4. Discussion

Our study results suggest that experience in the teaching role is associated with aspects of physicians’ job-related well-being. We were able to demonstrate corresponding correlations of this role with job satisfaction and job motivation, but not with emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, we found that teaching experience plays an important role in physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy. We also found higher teaching-related self-efficacy scores for the group of physicians who had already completed didactics training compared to the group without previous training.

Our first hypothesis could not be confirmed: Teaching-related self-efficacy did not correlate significantly with physicians’ emotional exhaustion. There could be several reasons for this, including the fact that emotional exhaustion is multifactorial. We were thus unable to show the influence of teaching-related self-efficacy separately in our study. In contrast to the consideration of job motivation and job satisfaction, private life also represents a stronger influencing factor here. Klusmann and Aldrup [51], for example, found in their study that both positive and negative private experiences can have an impact on the emotional exhaustion of teachers. In subsequent studies, it would be useful to introduce a more holistic measure of emotional exhaustion as a control variable. At the same time, it is debatable whether it is fundamentally expedient to evaluate the emotional exhaustion scale as an indicator variable for general job-related well-being in future studies, even though the three aspects had a Cronbach’s alpha of a=0.89. For reasons of consistency, a reduction to four values was chosen for all scales. Applying the original number of values might have allowed a more differentiated picture.

Our results further confirm our assumption of a correlation between teaching-related self-efficacy and job motivation and job satisfaction. It seems logical that those who see themselves as competent and self-efficacious in their work are also more satisfied and motivated in their jobs. Job satisfaction and job motivation are dependent on many external and individual factors outside the field of teaching. Job satisfaction, for example, correlates with the “sense of belonging to the hospital” and emotional well-being [52]. In other studies, job motivation is positively associated with work-life balance [53]. A positive influence on teaching-related self-efficacy appears to be easier to achieve through targeted training measures than, for example, the manipulation of variables such as a sense of belonging or work-life balance.

Like Prieto and Altmaier [54], we were able to demonstrate a positive correlation between physicians’ teaching experience and their teaching-related self-efficacy. Those who had spent a longer period of time in teaching had a greater chance of having had lasting experience of success, which is an important source of teaching-related self-efficacy [43].

In our study, the groups of participants who had previously completed non-subject-specific university didactics training differed significantly in their teaching-related self-efficacy from those who had not yet completed any training at the time of the study [45], [55]. Future research could clarify these findings through interventional study designs, e.g., with regard to the question of which training content or which didactic methods are most conducive to teaching-related self-efficacy.

By offering subject-specific didactics training, medical faculties and university hospitals can directly promote the teaching-related self-efficacy of their employees and thus potentially have a positive influence on their job-related well-being. If necessary, initial course offerings could also be made during medical studies, e.g., to prepare medical students for didactic activities as instructors or peer teachers. In addition, teaching in the clinic should be prioritized more strongly, in the form of extensive didactics training before the first teaching session, while at the same time relieving students of their daily tasks.

Various limitations of the present study should be mentioned: Our sample can be characterized as an opportunistic sample collected monocentrically. However, since local conditions differ between different university hospitals and medical faculties, its generalizability is limited. Furthermore, in the theoretical derivation of our hypotheses, we argued with causal justifications, for example with regard to the role of self-efficacy in teaching as an influencing factor on job-related well-being However, due to the cross-sectional design of our predominantly correlative study, we cannot draw any causal conclusions. In addition, we were unable to capture some potentially relevant influencing factors in our study, such as physicians’ intrapersonal dispositions relevant to teaching or the extent of teaching actually undertaken. Furthermore, the physicians in our sample with more teaching experience were more likely to have previously completed medical didactic training. The correlations themselves showed only small to medium effects (see table 3 [Tab. 3]), but these are large constructs that affect the entire profession and the results should be interpreted in this light. Furthermore, with regard to the calculated analysis of variance, it should be noted that when grouping the participating lecturers with regard to their teaching experience, their age could not also be taken into account as a potentially independently relevant variable. Finally, when comparing individuals with and without previous didactics training, it was not specified which type of didactics training the respondents had completed. This could also be associated with distortion effects.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we were able to show positive correlations between physicians’ teaching-related self-efficacy and their job satisfaction and job motivation. In addition, teaching-related self-efficacy correlated positively with teaching experience and showed higher levels among physicians who had previously completed didactic training. These findings make it clear that an environment can be created at medical faculties that promotes teaching-related self-efficacy, e.g., by offering low-threshold, accessible but mandatory didactics training. In addition, young doctors at university hospitals should be involved in teaching at an early stage so that they can gain their first teaching experience and acquire didactic skills in parallel with medical and technical skills.

Authors’ ORCIDs

- Benjamin Kiver: [0009-0005-1053-0229]

- Pascal O. Berberat: [0000-0001-5022-5265]

- Martin Gartmeier: [0000-0002-5025-0003]

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Sterz J, Britz V, Carstensen P, Kollewe T, Voß S, Stefanescu M, Schreckenbach T, Verboket RD, Rüsseler M. Der Chirurg im Spagat–Lehre im klinischen Alltag [The surgeon's balancing act-Teaching in the clinical routine]. Chirurg. 2022;93(3):286-291. DOI: 10.1007/s00104-021-01470-1[2] Hillienhof A. Didaktik im Studium: Fit für die Lehre. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;13(1). Zugänglich unter/available from: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/didaktik-im-studium-fit-fuer-die-lehre-8a7d06d2-7654-4af6-9236-d7e475217bfc

[3] Steinert Y, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):963-968. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002695

[4] Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452-466. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bee61

[5] Verhaeghe R, Vlerick P, Gemmel P, Maele GV, Backer GD. Impact of recurrent changes in the work environment on nurses’ psychological well-being and sickness absence. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(6):646-656. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04058.x

[6] Wright TA, Cropanzano R. The role of psychological well-being in job performance:: a fresh look at an age-old quest. Organ Dynam. 2004;33(4):338-351. DOI: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.09.002

[7] Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Pearson Education; 1986. p.23-28.

[8] Lent RW, Brown SD. Social cognitive approach to career development: An overview. Career Dev Q. 1996;44(4):310-321. DOI: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00448.x

[9] Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. In: Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Charlette (NC): Information Age Publishing; 2006. p.307-337.

[10] Tschannen-Moran M, Hoy AW. The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teach Teach Educ. 2007;23(6):944-956. DOI: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.003

[11] Gibson S, Dembo MH. Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. J Educ Psychol. 1984;76(4):569-581. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0663.76.4.569

[12] Klassen RM, Chiu MM. Effects on teachers' self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. J Educ Psychol. 2010;102(3):741-756. DOI: 10.1037/a0019237

[13] Klassen RM, Chiu MM. The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: Influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2011;36(2):114-129. DOI: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002

[14] Muijs D, Reynolds D. Teachers' beliefs and behaviors: What really matters? J Classroom Interact. 2002;37(2):3-15.

[15] Wu H, Li S, Zheng J, Guo J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1742964. DOI: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1742964

[16] Demirören M, Turan S, Öztuna D. Medical students’ self-efficacy in problem-based learning and its relationship with self-regulated learning. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):30049. DOI: 10.3402/meo.v21.30049

[17] Tipwong A, Hall NC, Snell L, Chamnan P, Moreno M, Harley JM. Clinical teaching self-efficacy positively predicts professional fulfillment and negatively predicts burnout amongst Thai physicians: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):361. DOI: 10.1186/s12909-024-05325-1

[18] Elster MJ, O’Sullivan PS, Muller-Juge V, Sheu L, Kaiser SV, Hauer KE. Does being a coach benefit clinician-educators? A mixed methods study of faculty self-efficacy, job satisfaction and burnout. Perspect Med Educ. 2022;11(1):45-52. DOI: 10.1007/s40037-021-00676-7

[19] Rothmann S. Job satisfaction, occupational stress, burnout and work engagement as components of work-related wellbeing. SA J Indust Pychol. 2008;34(3):a424. DOI: 10.4102/sajip.v34i3.424

[20] Hwang H, Hur WM, Shin Y. Emotional exhaustion among the South Korean workforce before and after COVID-19. Psychol Psychother. 2021;94(2):371-381. DOI: 10.1111/papt.12309

[21] Shirom A. Burnout in work organizations. In: Cooper CL, Robertson IT, editors. Internatioal review of industrial and organizational psychology. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. p.25-48.

[22] Zohar D. Predicting burnout with a hassle-based measure of role demands. J Organ Behav. 1997;18(2):101-115.

[23] Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Carvalho YT, Dutra AS, Amaral MB, Queiroz TT. The relation between burnout and sleep disorders in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):438-444. DOI: 10.1007/s40596-014-0093-z

[24] Thommasen HV, Lavanchy M, Connelly I, Berkowitz J, Grzybowski S. Mental health, job satisfaction, and intention to relocate. Opinions of physicians in rural British Columbia. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:737-744.

[25] López-López IM, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Cañadas GR, De la Fuente EI, Albendín-García L, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Prevalence of burnout in mental health nurses and related factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mental Health Nurs. 2019;28(5):1035-1044. DOI: 10.1111/inm.12606

[26] Moon TW, Hur WM. Emotional intelligence, emotional exhaustion, and job performance. Soc Behav Pers. 2011;39(8):1087-1096. DOI: 10.2224/sbp.2011.39.8.1087

[27] Kuok AC, Teixeira V, Forlin C, Monteiro E, Correia A. The effect of self-efficacy and role understanding on teachers’ emotional exhaustion and work engagement in inclusive education in Macao (SAR). Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2022;69(5):1736-1754. DOI: 10.1080/1034912X.2020.1808949

[28] Locke EA. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In: Dunnette MD, Triandis HC, editors. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1976.

[29] Aziri B. Job satisfaction: A literature review. Manag Res Pract. 2011;3(4):77-86.

[30] Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, Patton GK. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(3):376-407. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376

[31] Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(2):105-112. DOI: 10.1136/oem.2002.006734

[32] Bradley DE, Roberts JA. Self-employment and job satisfaction: investigating the role of self-efficacy, depression, and seniority. J Small Business Manag. 2004;42(1):37-58. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-627X.2004.00096.x

[33] Gkolia A, Belias D, Koustelios A. Teacher's job satisfaction and selfefficacy: A review. Eur Sci J. 2014;10(22):321-342.

[34] Judge TA, Bono JE. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(1):80-92. DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80

[35] Burić I, Moe A. What makes teachers enthusiastic: The interplay of positive affect, self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Teach Teach Educ. 2020;89:103008. DOI: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.103008

[36] Ganta VC. Motivation in the workplace to improve the employee performance. Int J Engin Technol Manag Appl Sci. 2014;2(6):221-230. DOI: 10.18231/2454-9150.2018.0713

[37] Lăzăroiu G. Employee motivation and job performance. Ling Phil Invest. 2015;14:97-102.

[38] D’Alleva A, Coco A, Pelusi G, Gatti C, Bussotti P, Lazzari D, Bracci M, Minelli A, Gasperini B, Prospero E. Impact of Work Motivation on Occupational Health in Healthcare Workers. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(23):3056. DOI: 10.3390/healthcare11233056

[39] Carstensen LL. Socioemotional selectivity theory: The role of perceived endings in human motivation. Gerontologist. 2021;61(8):1188-1196. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnab116

[40] Schunk DH. Self-efficacy, motivation, and performance. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1995;7(2):112-137. DOI: 10.1080/10413209508406961

[41] Demir S. The role of self-efficacy in job satisfaction, organizational commitment, motivation and job involvement. Eur J Educ Res. 2020;20(85):205-224.

[42] Heslin PA, Klehe UC. Self-efficacy. In: Rogelberg SG, editor. Encyclopedia Of Industrial/Organizational Psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2006. p.705-708.

[43] Gale J, Alemdar M, Cappelli C, Morris D. A mixed methods study of self-efficacy, the sources of self-efficacy, and teaching experience. Front Educ. 2021;6:750599. DOI: 10.3389/feduc.2021.750599

[44] Ammentorp J, Sabroe S, Kofoed P-E, Mainz J. The effect of training in communication skills on medical doctors’ and nurses’ self-efficacy: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):270-277. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.012

[45] de Sousa Mata ÁN, Morais de Azevedo KP, Braga LP, Bandeira Silva de Medeiros GC, de Oliveira Segundo VH, Machado Bezerra IN, Pimenta ID, Nicolás IM, Piuvezam G. Training in communication skills for self-efficacy of health professionals: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):30. DOI: 10.1186/s12960-021-00574-3

[46] Tzivinikou S. The impact of an in-service training program on the self-efficacy of special and general education teachers. Probl Educ 21st Cent. 2015;64(1):95-107.

[47] Pfitzner-Eden F, Thiel F, Horsley J. An adapted measure of teacher self-efficacy for preservice teachers: Exploring its validity across two countries. Z Päd Psychol. 2014;28(3):83-92. DOI: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000125

[48] Bakker A, Demerouti E, Schaufeli W. Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands–resources model. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2003;12(4):393-417. DOI: 10.1080/13594320344000165

[49] Maslach C. Stress, burnout, and workaholism. In: Kilburg RR, Nathan PE, Thoreson RW, editors. Professionals in distress: Issues, syndormes, and solutaions in psychology. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 1986. p.53-75. DOI: 10.1037/10056-004

[50] Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J Appl Psychol. 1975;60(2):159-170. DOI: 10.1037/h0076546

[51] Klusmann U, Aldrup K, Schmidt J, Lüdtke O. Is emotional exhaustion only the result of work experiences? A diary study on daily hassles and uplifts in different life domains. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34(2):173-190. DOI: 10.1080/10615806.2020.1845430

[52] Capone V, Borrelli R, Marino L, Schettino G. Mental well-being and job satisfaction of hospital physicians during COVID-19: relationships with efficacy beliefs, organizational support, and organizational non-technical skills. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3734. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19063734

[53] Guo B, Qiang B, Zhou J, Yang X, Qiu X, Qiao Z, Yang Y, Cao D. The relationship between achievement motivation and job performance among Chinese physicians: a conditional process analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021(1):6646980. DOI: 10.1155/2021/6646980

[54] Prieto LR, Altmaier EM. The relationship of prior training and previous teaching experience to self-efficacy among graduate teaching assistants. Res High Educ. 1994;35:481-497. DOI: 10.1007/BF02496384

[55] Watson G. Technology professional development: Long-term effects on teacher self-efficacy. J Technol Teach Educ. 2006;14(1):151-166.