[Qualität der bakteriologischen infektionsserologischen Verfahren in Deutschland: Auswertung der Ringversuche 2019 – Beitrag der Qualitätssicherungskommission der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Hygiene und Mikrobiologie]

Ulyana Gräf 1,2Klaus-Peter Hunfeld 1,2,3

Sabine Goseberg 2

1 Institute for Laboratory Medicine, Microbiology and Infection Control, Northwest Medical Centre, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

2 INSTAND e.V., Düsseldorf, Germany

3 German Society for Hygiene and Microbiology (DGHM), Quality Assurance Commission, Hannover, Germany

Zusammenfassung

Unter Routinebedingungen werden in jedem Labor Ringversuche durchgeführt. Dies ist Voraussetzung, um zuverlässige labormedizinische Untersuchungen durchführen zu können. Ringversuche dienen dem Zweck, qualitätsgesicherte Prozesse nachzuweisen und sicherzustellen. Um die Untersuchungsqualität der teilnehmenden Labore beurteilen zu können, werden die Ergebnisse der zu testenden und für alle Labore identischen Proben gesammelt und statistisch ausgewertet (Richtlinie der Bundesärztekammer zur Qualitätssicherung laboratoriumsmedizinischer Untersuchungen 2023). Die Ergebnisse der Ringversuche 2019 werden in der folgenden Arbeit genauer dargestellt.

Schlüsselwörter

Ringversuch, qualitätsgesicherter Prozess

1 Introduction

Specific antibodies are produced after the body has been exposed to microorganisms. The detection of these antibodies in the patient’s serum allows conclusions to be drawn about the presence of pathogens. This is the aim of bacterial infection serology tests [1]. Serum is generally used as the sample matrix. Urine can also be used to directly detect certain pathogens. In addition, molecular biological testing, which enables the direct detection of pathogens, is increasingly being used to diagnose infectious diseases in clinical laboratories.

External quality assurance (EQA) in laboratories is ensured by interlaboratory tests. These are a good means of obtaining a qualified overview of the quality and efficiency of the various serological methods currently available [2]. Interlaboratory tests assess the methods used, irrespective of the manufacturer, in order to guarantee quality, as well as to make statements about the measurement accuracy and measurement quality of the participating institutes. The external quality controls, which are mandatory for every laboratory, compare the test quality of the serological assays on the market and help to continuously improve the quality of diagnostics testing and treatment [3]. Such surveys enable laboratories to introduce transparent and verifiable external quality controls. These controls comprehensively evaluate the diagnostic properties of modern tests. By conducting these surveys, laboratories can ensure that their tests are accurate and reliable. They can also identify weaknesses and recognize areas for improvement. This contributes to a higher quality of diagnostic results. Systematic reviews are necessary to maintain and continuously improve diagnostic testing standards.

This report presents and discusses the results of INSTAND’s 2019 EQA schemes for bacterial infection serology tests.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample collection and implementation

The EQA test samples are obtained from healthy donors or donors who have had a previous infection. Informed consent is obtained from the donors beforehand.

Every laboratory participating in INSTAND e.V.’s EQA schemes receive two serum samples per year to detect specific antibodies against yersinia, Bordetella pertussis, mycoplasma, campylobacter and Coxiella, respectively. All other parameters (including diagnostic inflammatory markers) are tested two to four times a year depending on the participant. For EQA schemes 313 and 316, participants receive two pre-fixed slides and two urine samples that have been spiked with the inactivated cell culture supernatant of a Chlamydia trachomatis culture. The antibody reactivity of the serum samples is blinded for the individual participants. Furthermore, no detailed clinical information is issued to guarantee maximum objectivity with regard to the testing and reporting of the laboratory results. The microbiological stability, sterility and homogeneity of the samples are ensured during production (in accordance with DIN ISO 13528 [4], Annex B), and the samples have tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [5].

2.2 Target values

The target values for the qualitative, semi-quantitative and quantitative test results (if applicable for the EQAs) as well as the comprehensive diagnostic evaluation and the interpretative comments are based on the results of 3 to 10 designated reference laboratories. If a uniform target value for a particular quantitative parameter or analytical method cannot be determined, the robust mean (Algorithm A according to DIN ISO 13528 [4], Annex C) of a collective is stipulated as being the target value for a specific test method [5].

With respect to the qualitative test results either the mode of the results of the reference laboratories or – if a uniform target value for a particular parameter or analytical method cannot be determined – the mode of the results of the participants is set as the target-value. The laboratory receives a passing grade if its results correspond to those reported by the reference laboratories. Combinations of results or comments are also accepted where applicable.

Test results are only evaluated if the number of participants using a certain assay or test method (values obtained with the same method and/or reagent manufacturer combination) is higher than 8. The evaluation of smaller numbers of participants by consensus value may lead to statistically invalid assessments in some cases. Therefore, no evaluation of a smaller number of participants (n≤8) is performed using a consensus value. In such cases, participants only receive a participation certificate.

3 Results

3.1 Tetanus serology (310)

All samples were donated by healthy blood donors. The results for samples 31 and 32 showed that long term protection was present and that titers should be checked after 5 to 10 years. Sample 61 showed adequate immune protection, however, a booster shot would lead to long-term immunity. The donor of sample 62 will need a booster shot in about 5 to 10 years because the sample revealed sufficient protective immunity at the moment [6]. The pass rates ranged from 81.4% to 93.3%.

3.2 Syphilis serology (311)

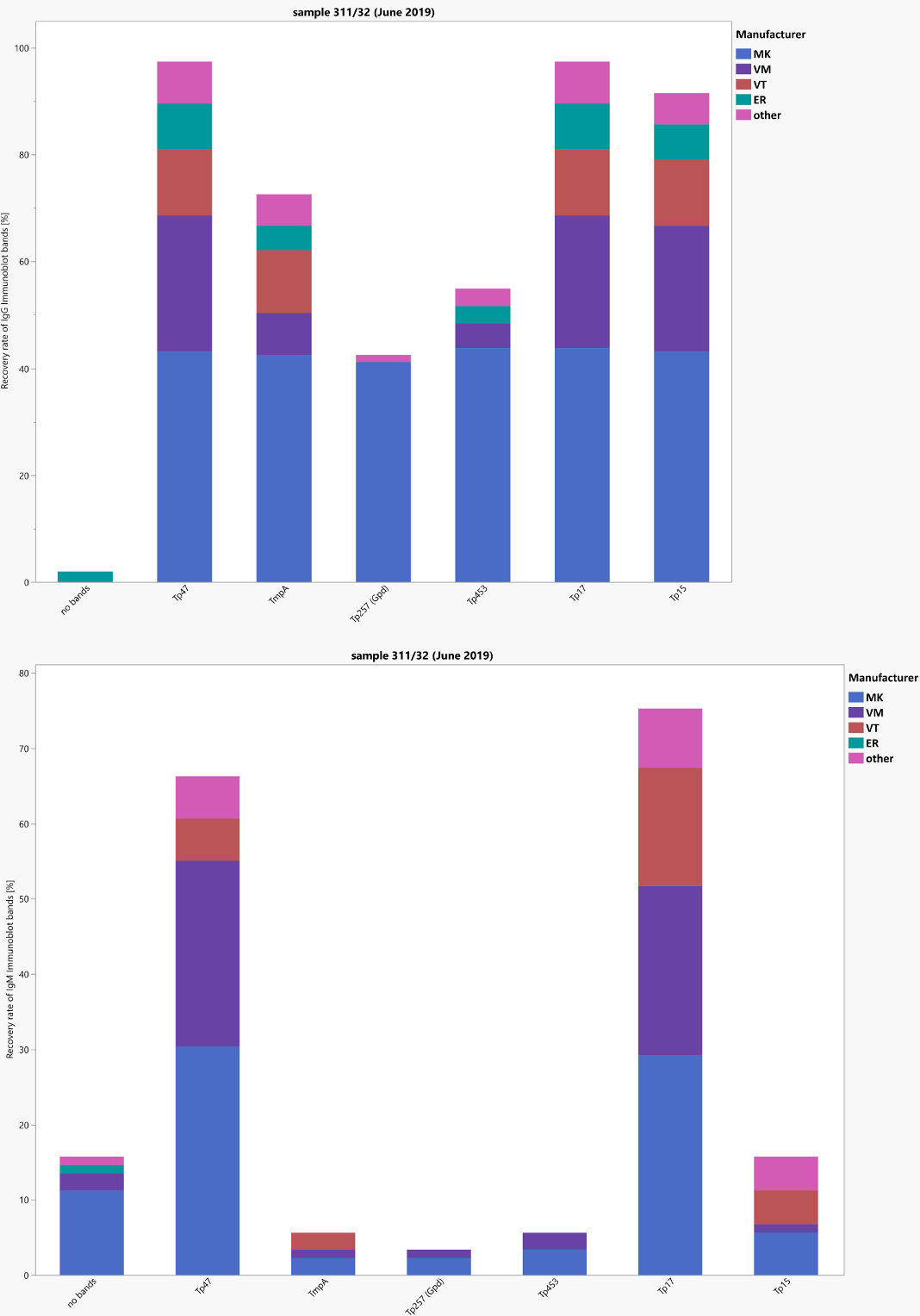

The positive sample 32 was obtained from a patient with an initially unknown syphilis infection which was later deemed sufficiently treated one month after treatment (titer (modal: Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA): 5,120, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL): 8; fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption immunoglobulin M (FTA-ABS-IgM) test: 40; enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and immunoblot positive for immunoglobulin G (IgG) and borderline/positive for IgM)). Even without clinical information, the results clearly point to an active infection that needs further treatment. Unfortunately, positive IgM-results were missed by some laboratories using EIA and immunoblot despite diagnostic FTA-ABS-IgM-titers of 10 to 160. The negative sample 31 originated from a healthy blood donor without clinical or serological evidence of a syphilis infection in his medical history. With respect to the interpretative comments, only comments or combinations of comments that pointed to an active infection in need of treatment were accepted. Overall pass rates were less encouraging than during recent surveys due to the difficulties some laboratories had in detecting IgM antibodies. The new screening tests (chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA), chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA), etc.) could not be quantitatively evaluated. Figure 1 [Fig. 1] shows the distribution of the immunoblot bands in the different assays for sample 32.

Figure 1: Manufacturer-specific distribution of immunoblot bands for sample 32 (IgG and IgM)

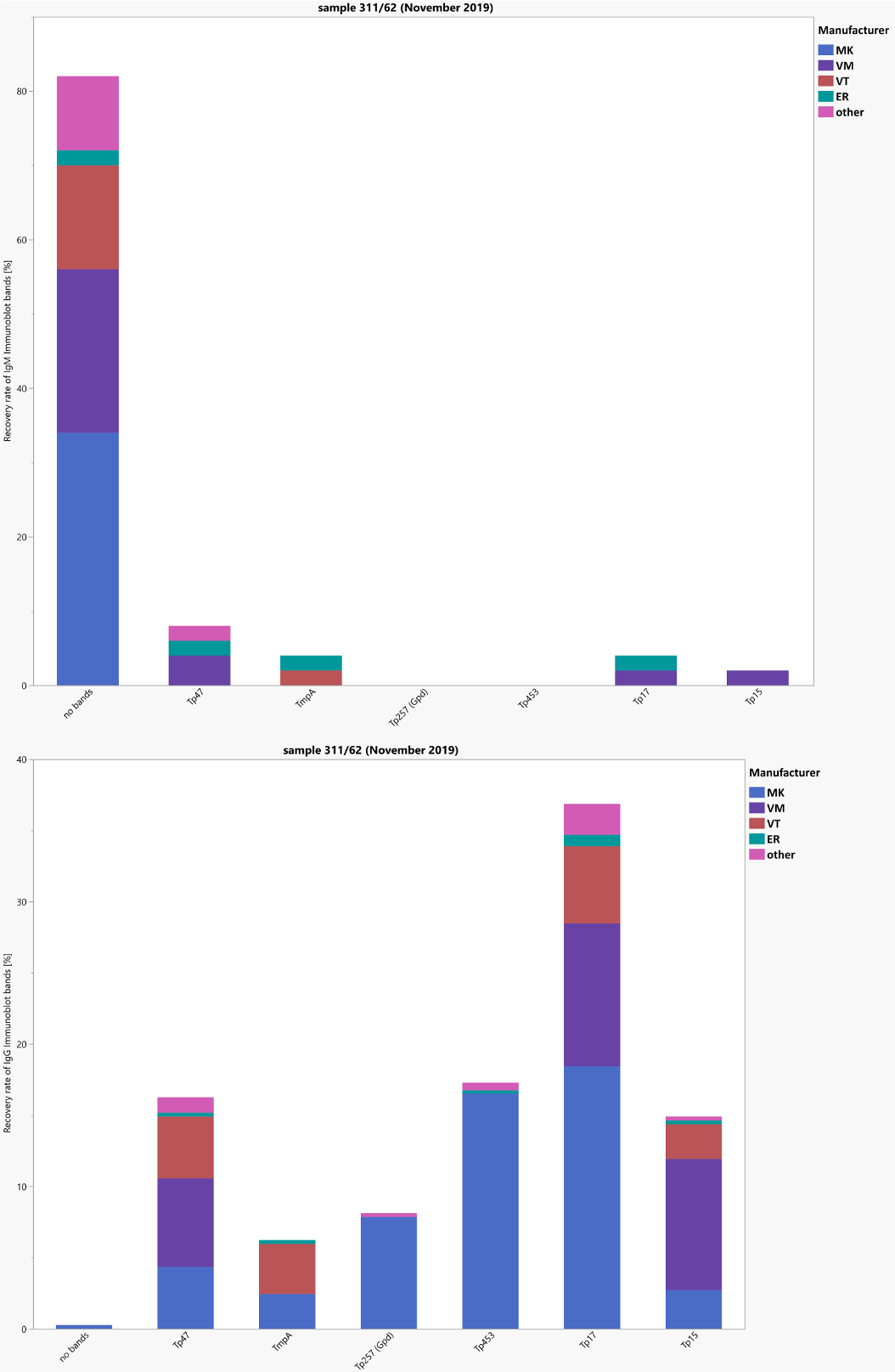

The positive sample 62 (target values: TPPA: 320 polyval. enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): positive, IgG-ELISA positive, VDRL: 0–0.99 positive, borderline, negative, FTA-ABS-IgG: 80, FTA-ABS-IgM and IgM-ELISA negative) was donated during a blood drive by an individual treated for a syphilis infection several years ago. The other sample (sample 61) was donated by a healthy blood donor. Here most participants and the reference laboratories reported negative test results for T. pallidum-specific antibodies. The overall pass rates for most of the test methods (pass rates: 71%–100%) and the interpretative comments (pass rate: 77.5%) were one again encouraging. Figure 2 [Fig. 2] shows the distribution of the immunoblot bands in the different assays for sample 62.

Figure 2: Manufacturer-specific distribution of immunoblot bands for sample 62 (IgG and IgM)

3.3 Chlamydia trachomatis serology (312)

All samples were donated by healthy blood donors. Samples 31, 61 and 62 showed no serological evidence of an infection with C. trachomatis. The positive IgG and borderline immunoglobulin A (IgA) reactivity of sample 32 are consistent with either a past or a possibly active infection. The overall pass rate was between 93% and 100%. The pass rates for the interpretative comments (98.8%–9.2%) were encouraging.

3.4 Chlamydia trachomatis (direct detection of Chlamydia antigen (313))

Samples 32 and 61 were produced from sterile urine that tested negative for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Samples 31 and 62 were prepared from sterile filtered urine spiked with Chlamydia trachomatis from an inactivated CT culture. The pass rate for the negative samples 32 and 61, with no evidence of infection, were 92.9%–100%. The results for the positive samples 32 and 61 were 100%.

3.5 Chlamydia pneumonia serology (314)

Both the seronegative samples 31 and 61 and the seropositive samples 32 and 62 were donated by clinically healthy blood donors without symptoms of a respiratory infection in their recent medical history.

Diagnostically, there was no serological evidence of an infection in samples 31 and 61. For samples 32 and 62, a positive IgG reactivity as well as a specific positive/borderline IgA response could be detected, pointing to a recent or active Chlamydia pneumonia infection. These results were also reported by most laboratories in their diagnostic comments (pass rates: 95%–97%).

3.6 Yersinia serology (315)

The positive sample 31 was obtained from an otherwise healthy blood donor with a history of a Yersinia infection several years ago. The different test systems showed specific IgG reactivity. The WIDAL test and the immunoassays remained negative for specific IgM and IgA antibodies. This test constellation including the negative WIDAL test clearly points to a past infection. Sample 32 was obtained from a healthy blood donor without evidence of gastroenteritis in his recent medical history. Here no negative results were reported. Overall, pass rates for the different assays and the clinical comments were less encouraging then during our recent surveys, mainly due to some false negative IgG test results for sample 31 (67%–100%).

3.7 Chlamydia trachomatis IFT (316)

In the case of direct C. trachomatis (CT) detection by immune fluorescent testing (IFT), the negative and positive CT samples were fixed on slides before shipment. The slides of the negative samples 32 and 61 were coated with non-infected squamous epithelial cells of a urine sediment. The coating of the slides for the positive samples 31 and 62 consisted of squamous epithelial cells from a urine sediment to which C. trachomatis from a culture supernatant were added. The pass rates ranged between 86% and 100% for both, the analytics and the overall diagnostic assessment.

3.8 Bordetella pertussis-serology (317)

Samples 61 and 62 were donated by healthy blood donors without evidence of any recent respiratory infections. Both samples tested negative for specific antibodies against B. pertussis and showed no indication of an active or recent infection. The overall pass rates were between 93% and 100%.

3.9 Diphtheria serology (318)

From a serological point of view, it can be assumed that the donors of samples 31 and 61 had adequate immune protection. A booster would provide long-term protection. The donor of sample 32, on the other hand, did not have adequate immune protection and a booster is recommended. The donor of sample 62 had a sufficient immune protection and will need a booster shot in about 5 to 10 years. The overall pass rates for the qualitative analysis were 72% to 94%. The pass rate for the quantitative analysis was 81% to 83%.

3.10 Campylobacter-serology (319)

Samples 31 and 32 originated from healthy blood donors. Sample 32 showed weekly reactive test results upon testing for IgG antibodies by ELISA and Immunoblot and a negative test result for specific IgM and IgA antibodies by complement fixation testing (CFT). Some laboratories missed the weak IgG reactivity. This is why the test results and the interpretative comments have been graded more generously, leading to pass rates of 16% to 100%.

3.11 Procalcitonin (320)

Samples 31 and 61 were obtained from clinically healthy blood donors. A systemic infection (sepsis) is rather unlikely. Samples 32 and 62 were produced from pooled left-over sera from septic patients and point to a systemic infection (sepsis). The overall pass rates were between 81% and 100%. The pass rates for the interpretative comments ranged between 84% and 90%.

3.12 Streptococcal serology (321)

All four samples came from clinically healthy blood donors. However, the values of sample 31 and 62 indicate that an infection must have been present, likewise for sample 32. The pass rates for the different analytical methods to detect specific antibody concentrations against streptodornase and streptolysin-O were in the range of 92% to 100%.

3.13 Rheumatoid factor (323)

Sample 31 was obtained from a clinically healthy blood donor. For the positive sample 32 we pooled patient sera that was positive for rheumatoid factor with the serum of a healthy donor. The overall pass rates ranged between 92% and 96%.

3.14 Mycoplasma pneumonia serology (324)

Sample 61 was donated by a healthy blood donor during the summer months. The sample exhibited negative IgG, IgA, and IgM reactivity and there was no evidence of infection. There was also no evidence of a respiratory infection in this donor. Sample 62 was obtained from a clinically ill individual with a positive PCR for M. pneumoniae. Serological test results corresponded to a current or very recent infection with a positive phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (titer: 180) and positive IgG, IgM, and IgA reactivity. A few tests showed negative IgG results. However, the overall pass rates for the different test methods and the interpretative comments were mostly encouraging (overall pass rates: 5% to 100%; interpretative comment: 82%).

3.15 Coxiella burnetii serology (325)

Samples 61 and 62 were donated by a healthy blood donor without evidence of a recent infection and tested negative for C. burnetii antibodies. The overall pass rates ranged between 80% and 100%. The pass rate for the interpretative comments was an encouraging 100%.

3.16 Salmonella serology (331)

Samples 32, 61 and 62 were obtained from a healthy blood donor without evidence of a salmonella infection. Sample 31 was prepared from rabbit sera containing high titers of antibodies against Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi (9, 12, [Vi]: d: –) with anti-S. Typhi-O titers of 400 (100–1,600) upon direct agglutination using the WIDAL test. Consequently, EIA tests for human anti-salmonella antibodies showed negative results for this sample. Accordingly, negative EIA test results for this sample were also accepted and medical comments were accepted depending on individual test methods used (over all pass rates of 53% to 100%).

3.17 Borrelia burgdorferi (332)

Samples 31, 32, 61 and 62 were obtained from clinically healthy blood donors. Sample 31 yielded negative test results for most participants and the reference laboratories, except for some laboratories reporting false positive IgM reactivity (mainly against p39). For sample 32, most participants and the reference laboratories reported weak reactivity, mainly against OspC. These test results demonstrate the problems that have been identified with respect to specific IgM testing against Borrelia burgdorferi: without clinical evidence of an infection, the results of such test frequently indicate a non-specific reactivity of the sample. To avoid such false positive IgM test results, some international experts no longer recommend IgM testing of Lyme borreliosis serology if clinical symptoms last for more than 6 weeks. In our survey, both blood donors had no evidence of tick bites or any symptoms of acute Lyme borreliosis in their medical history. Overall pass rates, including those for the interpretative comments, were less encouraging than in the last surveys (22% to 100%). A graphic illustration of immunoblot banding distribution was left out this time because mainly p41 and OspC were identified in sample 31 by immunoblot testing

3.18 Helicobacter pylori serology (334)

The negative samples 31 and 61 were obtained from healthy blood donors. The positive samples 32 and 62 both showed positive IgG and borderline IgA antibody reactivity by EIA and immunoblot testing. The samples originated from two different helicobacter-positive patients and were obtained after successful eradication therapy. The constellation of results was interpreted as corresponding to an infection or colonization with helicobacter both by the reference laboratories and by most of the participants (overall pass rates: 94% to 99%).

4 Discussion

The evaluation of the 2019 laboratory survey of bacterial infection serology was generally unproblematic. The pass rates for most of the tested parameters were in line with previous results. However, several problems were identified for the EQAs for the syphilis and borrelia serology carried out in spring 2019. Some laboratories missed positive IgM results in the syphilis serology when they used EIA and immunoblot despite diagnostic FTA-ABS-IgM titers of 10 to 160. The problem connected to the borrelia serology, however, was that some laboratories reported a false positive IgM reactivity (mainly against p39). These affected both the participants’ clinical interpretation and the performance of the assay systems used to analyze the samples. A follow-up survey was initiated with the aim of rectifying these previously encountered problems. The re-examination ultimately showed typical results. This confirmed the reliability of the tests. It also showed that these two parameters, together with procalcitonin or anti-streptococcal antibodies, are considered the most reproducible diagnostic methods.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Rüttger S, Müller I, Hunfeld KP. Zur Qualität bakteriologisch-infektionsserologischer Verfahren in Deutschland: Auswertung der infektionsserologischen Ringversuche 2015 – Beitrag der Qualitätssicherungskommission der DGHM. GMS Z Forder Qualitatssich Med Lab. 2018;9:Doc03. DOI: 10.3205/lab000031[2] Verordnung über das Errichten, Betreiben und Anwenden von Medizinprodukten (Medizinprodukte-Betreiberverordnung - MPBetreibV), zuletzt geändert durch Art. 7 der Verordnung vom 21. April 2021 (BGBl. I S. 833). § 9 Qualitätssicherungssystem für medizinische Laboratorien.

[3] Bundesärztekammer. Richtlinie der Bundesärztekammer zur Qualitätssicherung laboratoriumsmedizinischer Untersuchungen Gemäß des Beschlusses des Vorstands der Bundesärztekammer in seiner Sitzung am 18.10.2019, zuletzt geändert durch Beschlussfassungen des Vorstands der Bundesärztekammer am 14.04.2023. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 2023 May 30. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2023.rili_baek_QS_Labor

[4] DIN ISO 13528:2022-08: Statistical methods for use in proficiency testing by interlaboratory comparison. Berlin: Beuth; 2022.

[5] DIN ISO 13528: 2020-09: Statistische Verfahren für Eignungsprüfungen durch Ringversuche (ISO 13528:2015, korrigierte Fassung 2016-10-15). Berlin: Beuth; 2016.

[6] Kuhlmann WD. Tetanus. Impfung, Impftiter und Impfreaktion. Koblenz: Zentrales Institut des Sanitätsdienstes der Bundeswehr; 1991.