Observation of development milestones during hearing testing of toddlers: Preliminary analysis

Annette Voswinckel 1Valentina Berlendis 1,2

Christof Stieger 1,3

1 Ear, Nose and Throat Clinic, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland

2 University Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy

3 Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Basel, Switzerland

Abstract

During pediatric audiometry besides evaluation of the hearing threshold, non-acoustic behavior can be observed. This retrospective study evaluates the feasibility and diagnostic value of standardized developmental observations conducted during audiometric testing of toddlers. The observations were categorized into symbolic, language and individuation development domains across six age groups from 9 months to >36 months.

In total 94 standardized observation forms with 37 children with confirmed hearing loss and 57 children with typical hearing across all six age groups have been recorded. This preliminary analysis includes 21 children in the age group from 18–24 months. Only few children demonstrated fully age-appropriate developmental profiles. Children with hearing loss showed age related symbolic development e.g., “smile of mastery” likely due to early intervention, while delays were noted in language and individuation domains. Children with typical hearing showed age-appropriate language development but delays in symbolic and individuation domains. The study concludes that standardized developmental observations by trained audiometrists are feasible during audiometric testing and potentially contribute for the diagnostic evaluation process.

Introduction

Play behavior is a universal phenomenon of early childhood development [1], [2], [3]. In both speech therapy and pediatric audiology, play is not only a mean of interaction, but also a valuable diagnostic tool.

Speech therapy

In the field of speech therapy, observational diagnostics have become increasingly established over the past decades [4]. This diagnostic approach is based on targeted observations during clearly defined play situations. Each play scenario is associated with typical developmental milestones, which allow to estimate a child’s developmental age [5]. While the primary focus is on assessing language development, aspects of symbolic and individuation development are considered to be equally important [6]. A complete observational diagnostic session conducted by a speech-language pathologist typically lasts more than one hour.

Audiology

Subjective audiometric tests with toddlers are performed in less than one hour.

The audiometrist chooses between visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA), play audiometry, or conventional audiometry based on the child’s age, cognitive abilities and behavioral responses, often determined through a trial-and-error approach. The primary criterion for test selection is the child's age. Besides early quantification of hearing loss, toddlers with manifold diseases are referred to the pediatric audiology in order to exclude hearing disabilities.

During audiometric assessments, an audiologist may observe developmental behaviors relevant to the child’s overall development. At our institution, these observations are documented in a standardized format and added to the patient’s medical records in addition to the audiogram. These observations are derived from playing situations in often unstressed conditions. Since pediatric assessments of physicians are often constrained by limited time and more invasive diagnostic procedures, the standardized observations from the audiometry may provide important additional hints for diagnosis.

The aim of this retrospective study was two-fold: 1) to evaluate the feasibility of standardized developmental observations made during audiometric testing in toddlers and 2) to evaluate potential differences between toddlers with and without hearing loss.

Material and methods

Standardized form

The standardized form for observation of the development profile form was created by an interdisciplinary team consisting of a speech-language pathologist, an audiometrist, a pediatric ENT (MD) and an audiologist (PhD). The form categorizes observed behaviors into three developmental domains, i.e. symbolic, language and individuation. Each developmental domain was subdivided into six age groups:

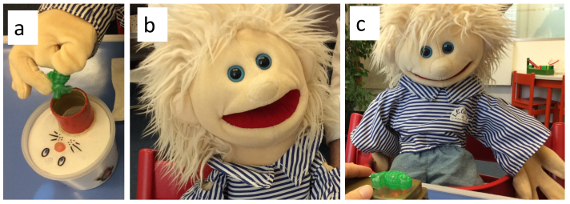

- 9–12 months (Figure 1 [Fig. 1])

- 12–18 months

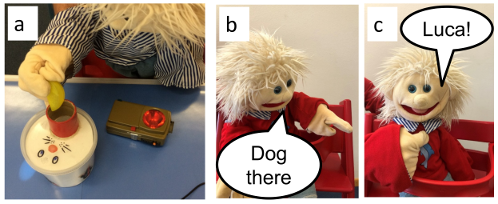

- 18–24 months (Figure 2 [Fig. 2])

- 24–30 months

- 30–36 months

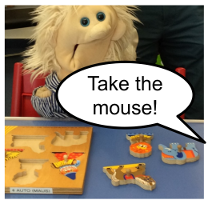

- Older than 36 months (Figure 3 [Fig. 3])

Figure 1: Example of the three observable developmental domains at 9–12 months of age: a) Symbolic development: Does the child hold small pieces with two fingers or with a fist grip. b) Language development: Does the child demonstrate referential eye contact? c) Individuation development: Can the child sit independently?

Figure 2: Examples of the three observable domains of development between 18 and 24 months. a) Symbolic development: Is the child conditionable? b) Language development: Does the child speak in one or two words? c) Individuation development: Does the child call themselves by their name?

Figure 3: Example of a language development domain at 24–30 months: Does the child understand the request and react with irritation (by giving an absurd request, since there is no mouse in this puzzle)?

The original form – used from 2017 to 2020 – was paper based. Since 2020, data have been entered into the digital clinical documentation system. We only analyzed digital data in this study. The form can be filled by an experienced audiometrist in approximately 5 min. Taking into account that some of the observation e.g. conditionable should be documented in any case in order to describe the quality of the audiometric measurement, we estimate the effective additional time to be less than 3 min. The audiometrists have been practically trained initially by a speech therapist during 10–15 audiometric sessions. In specific cases, the speech therapist supports on demand the audiometrist during the sessions.

The individual developmental profile is considered age-appropriate and homogeneous when at least one age related behavior is observed in each developmental domain. If not all domains are fulfilled at the real-age level, the observations are progressively extended to earlier age groups until all three domains show positive indicators. If age related topics are fulfilled, observation were extended to later age groups. While the primary data source was direct observation by the audiometrist, the form offers anamnestic responses from accompanying parents or therapists for some of the items. As an example, a “therapeutic” setting or participation in a “playgroup” of the children cannot be observed by the audiometrist during testing.

Subjects

A total of 94 children were included in the analysis, comprising 37 children with confirmed hearing loss and 57 children with typical hearing. The differentiation between the two groups based solely on the criteria of confirmed hearing loss which was treated with any kind of technical hearing systems. The mental status, cognitive status or the reason for referral to our tertial center was not considered as inclusion criteria. However, children with known multiple mental or physical deficits were excluded. The cohort was categorized into six age groups: 9–12 months, 12–18 months, 18–24 months, 24–30 months, 30–36 months, and over 36 months. The present preliminary analysis focuses on the 18–24-month age group.

For each child with hearing loss, at least one age-matched peer with typical hearing was selected to ensure comparability. Within the 18–24-month subgroup, data were available for 7 children with hearing loss using hearing aids and 14 age-matched children with typical hearing.

All participants were included under the general informed consent framework of the University Hospital of Basel. An ethics application for the retrospective analysis was approved by the local ethics committee (BASEC 2024-01974).

Results

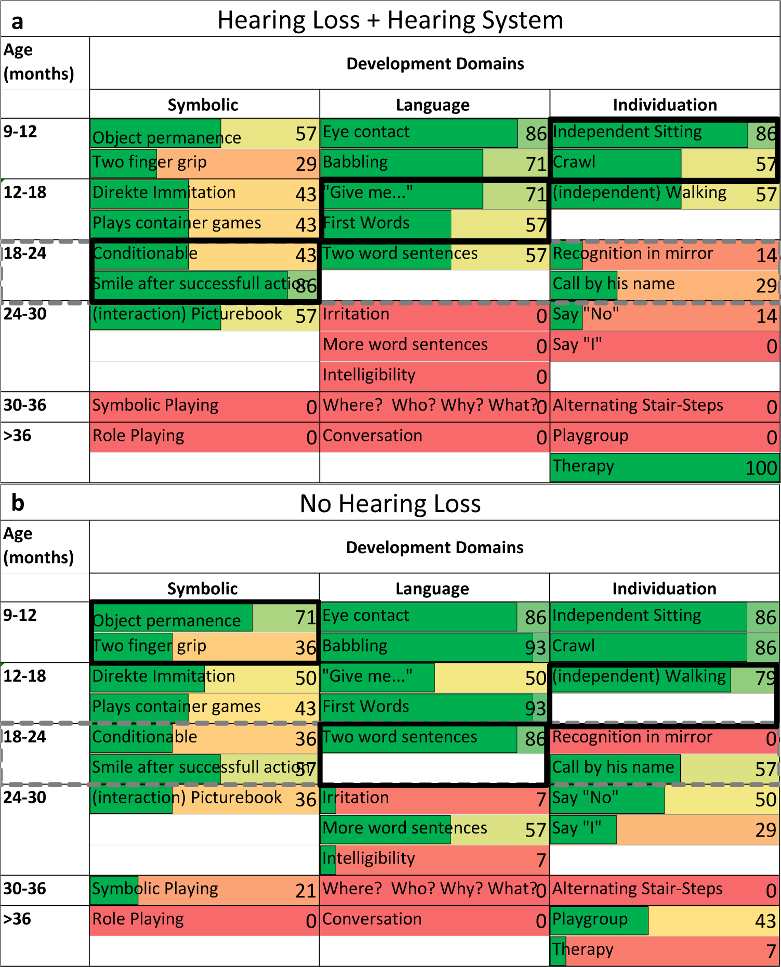

Table 1 [Tab. 1] shows the percentage of positive observations for 18–24 months old children with hearing loss wearing hearing devices and children with typical hearing.

Table 1: Percentage of positive observation in children with hearing loss (a) and with typical hearing (b) at the age between 18–24 months for all three development domains (symbolic, language, individuation). The green bar visualizes the percentage. The background of each cell is continuously colored from red (0%) over yellow (50%) to green (100%). Dashed box: age related normative development, black boxes: first age where more than 70% of positive observations per development domain are achieved. Item “Therapy” excluded.

In both groups, only few children demonstrated age-appropriate developmental profiles (dashed grey box). Additionally, most of the children showed a heterogeneous pattern of delayed development. A large proportion of children with hearing loss showed age-appropriate development in the symbolic domain i.e. “smile of mastery” and “eye contact”. On the other hand, development in language and individuation domains are delayed by one (12–18 months) and two (9–12 months) bins of age groups for most of the children (Figure 3 [Fig. 3], black boxes).

Children with typical hearing showed age-appropriate development in the language domain but individuation and symbolic domains are delayed by one age group (12–18 months) and two age groups (9–12 months).

Besides the comparison of the development profile we directly compared single items using Wilcoxon test. Children without hearing loss performed significantly better than their hearing-impaired peers in the following areas: “babbling”, “object permanence”, “first words”, “crawling”, “walking independently”, “referring to oneself by name”, “saying no” and “using the word I”.

Discussion

Interaction and estimation of children’s capabilities are important in pediatric audiometry. The standardized documented observations in this study originates from the audiology of a tertial hospital. Such institutions typically treat children with needs for extended diagnosis or treatment. This might explain the inhomogeneous and non-age related development in both analyzed groups of 18–24 months old children. Especially the group of children with typical hearing in this study does not constitute a typical control group, as many of the group members also present with developmental concerns. Only a few of these children had isolated, transient conditions e.g. control after middle ear infection.

100% of hearing-impaired children included in the study received early audiological and educational intervention. This specialized support with many communicative interactions with the therapist and the coaching of parents may explain the better performance observed in the hearing-impaired group in areas such as “eye contact” and “smiling after a successful action”.

Beside direct observations of the audiometrist we also included anamnestic data for the analysis. Such anamnestic data may introduce bias in the assessment of developmental profiles. For example “picture book” means that the child does not only scroll but there should be interaction like pointing. It should be considered whether these aspects could be more reliably recorded through standardized observation in future studies.

The current analysis focuses exclusively on children aged 18–24 months. Expanding the evaluation to include a broader age range is planned and considered essential to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of developmental trajectories in a tertial hospital.

The use of developmental profiles is well established in speech and language pathology for individual diagnostics. The assessment is longer in persecution and has more items. With our structured observations we could show differences between toddler with hearing loss and with typical hearing in our cohort. However, it remains to be shown whether these findings can also be used in individual cases to provide hints for further diagnosis or if only pathologic versus non pathologic development can be found.

In conclusion, standardized observations of symbolic, language and individuation development seem to be feasible by trained audiometrists and can reveal differences between different patient groups.

Notes

Conference presentation

This contribution was presented at the 27th Annual Conference of the German Society of Audiology and published as an abstract [7].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Lagro R. Baby Jahre. Entwicklung und Erziehung in den ersten vier Lebensjahren. Munich: Piper; 2019.[2] Hauser B. Spiel als notwendige Bedingung gelingender früher Sprachentwicklung. SAL-Bulletin. 2014;151:5-12.

[3] Lillard AS, Lerner MD, Hopkins EJ, Dore RA, Smith ED, Palmquist CM. The impact of pretend play on children's development: a review of the evidence. Psychol Bull. 2013 Jan;139(1):1-34. DOI: 10.1037/a0029321

[4] Zollinger B. Die Entdeckung der Sprache. Bern: Haupt Verlag; 2008.

[5] Jenni O. Die Kindliche Entwicklung verstehen. Berlin: Springer; 2021.

[6] Zollinger B. Und wenn sie nicht spielen können? SAL-Bulletin. 2014;153:5-16.

[7] Voswinckel A, Berlendis V, Genovese E, Stieger C. Evaluierung kommunikativer Entwicklungsmeilensteine während audiometrischen Untersuchungen bei Kleinkindern. In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Audiologie e. V.; ADANO, editors. 27. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Audiologie und Arbeitstagung der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutschsprachiger Audiologen, Neurootologen und Otologen. Göttingen, 19.-21.03.2025. Düsseldorf: German Medical Science GMS Publishing House; 2025. Doc200. DOI: 10.3205/25dga200