Biographical fairy tale work in trauma therapy: a clinical case study on the effects of creative writing

Katrin Roehlig 1,2,3,4Christina Vedar 1,2,5

Johannes Junker 4

Susann Kobus 1,2,6

1 Faculty of Medicine, University, Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

2 Center of Artistic Therapy, University Medicine Essen, Essen, Germany

3 Center Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Stuttgart, Germany

4 Nürtingen-Geislingen, University of Applied Sciences, Nürtingen, Germany

5 Alanus University of Arts and Social Sciences, Alfter, Germany

6 Department of Paediatrics I, University Hospital, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

Abstract

This article examines the effectiveness of a writing and creative therapy intervention that has patients with traumatic stress rewrite their life stories as fairy tales. The aim is to analyze the potentially stabilizing, structuring, and resilience-promoting effects of biographical fairy tale writing in a therapeutic context. The theoretical foundation is the integrative coping and resilience model BASIC Ph, which describes individual coping strategies. This study combines literature-based theoretical groundwork with a case study: as part of a therapeutic intervention, a semi-structured interview was conducted with a traumatized patient and subsequently evaluated using qualitative content analysis according to Mayring. The results indicate that rewriting one’s own life story as a fairy tale was perceived as emotionally relieving, structuring, and identity-strengthening. The findings support theoretical assumptions about narrative processes in trauma therapy. Biographical fairy tale work may represent a promising approach within the field of creative therapeutic methods – potentially extending beyond the medium of writing. Further research, particularly with bigger samples and regarding long-term effects, is needed.

Keywords

drama therapy, poetry therapy, biographical writing, fairy tale therapy, narrative integration, resilience, symbolic processing, basic ph model, narrative therapy

1 Introduction

Trauma describes a life-threatening situation that endangers physical integrity and cannot be controlled voluntarily [1], [2]. If the traumatic experience is not integrated and processed, a trauma-related disorder can occur [1]. With the introduction of the ICD-11, the definition of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was refined [3]. PTSD is now considered a response to an extremely threatening event accompanied by specific symptoms such as flashbacks or nightmares, pronounced avoidance behaviour, and a persistent feeling of increased threat (hyperarousal). The disorder can manifest immediately or with a delay and is typically associated with significant psychosocial impairment [3].

Traumatic experiences often leave deep traces in the self-image and worldview of those affected and should be seen as part of one's life history rather than isolated incidents [4]. Biographical victimization experiences represent risk factors that increase susceptibility to further stress and intensify the symptoms of trauma-related disorders [5].

A central issue for traumatized individuals is the difficulty of integrating the experience into a coherent and meaningful narrative. Research shows that traumatic memories often remain fragmented, disorganized, or even inexpressible – unlike flexible, adaptable autobiographical memories [6], [7]. The ability to relate to one’s own life story through coherent narratives is considered essential for identity and psychological stability [8]. The construction of life stories largely depends on the meaning we assign to our experiences [9]. Some therapeutic approaches build on this by aiming to improve the coherence of biographical narratives to support healthy psychological development [10]. Reconstructing a coherent and meaningful life story is not only therapeutically beneficial but also enables the integration of previously separated experiences [6].

Therapeutic writing – also referred to as poetry therapy, writing therapy, creative or biographical writing – uses structured language to help individuals cope with life crises and foster self-awareness and self-efficacy. These terms are often used interchangeably in literature, with the act of writing being the common denominator [11], [12], [13]. Creative writing, practiced in Germany for over four decades, is still considered a relatively young discipline despite its growing presence. It is influenced by adjacent disciplines such as literary studies, psychology, neuroscience, and creative therapies [14], [15]. It originated as a therapeutic approach in the American writing movement, which viewed it “as style, play, and therapy” [16]. Writing processes can serve various therapeutic functions, such as structuring internal experiences, promoting reflection, and enabling communication with oneself and others [13], [16]. Therapeutic writing is also closely linked to concepts such as mindfulness and emotion regulation and supports the ability to shape experiences into a coherent life story [11], [13], [17]. Within this context, a narrative reworking of one’s biography helps strengthen personal continuity and identity [11]. Biographical writing, when embedded in a therapeutic framework, aims to support present understanding and future orientation through reflection on the past, ultimately opening up new possibilities for action [18].

In trauma therapy, narrative approaches open pathways to creative therapeutic methods by initiating transformative processes, as reflected in the techniques and core principles of creative writing [11], [13]. Unlike trauma-focused exposure therapy, narrative approaches do not aim to reduce anxiety through verbal repetition of the traumatic event but instead provide emotional relief and symptom reduction by integrating traumatic memories into the autobiographical memory [8], [19]. By reconstructing biographical narratives, narrative methods enable the development of meaningful, alternative interpretations that reshape self-perception and help integrate distressing experiences [20], [21].

Even if the life stories of traumatized individuals are characterized by gaps and a lack of structure, their capacity for storytelling should not be regarded as deficient [6], [21]. The therapeutic process can support individuals in constructing a coherent narrative despite these gaps. The way such gaps are addressed depends largely on the therapist's attitude and the method used [21].

An illustrative example of narrative principles in therapy is found in the use of fairy tales. Described as narratives of the “marvelous” [22], fairy tales draw on archetypal themes and universal human experiences. Their symbolic language and clear structure enable a distance yet emotional examination with trauma. They provide a narrative framework within which individuals can reflect on their life stories [23]. The typical “happy ending” structure of fairy tales inspires hope and shows ways through crisis and resolution [24], [25]. In psychotherapy, fairy tales are often used as narrative tools to process inner conflicts [24]. They represent existential crises and their solutions [25]. Their structure often reflects biographical processes: from adversity, through challenge, to eventual liberation [25]. The struggles of fairy tale characters serve as metaphors for psychological conflicts, an enable an indirect engagement with personal distress [26]. Their surprising and creative solutions inspire belief in one's ability to overcome challenges [23]. Creative writing based on fairy tale structure provides a safe space for patients to articulate their experiences, process emotions, adopt new perspectives, and strengthen their sense of agency [11], [13]. The combination of symbolic fairy tale motifs with biographical reflection fosters the integration of trauma into personal life stories and supports the development of narrative coherence [8]. Fairy tales are rich in symbolic meaning [27]. In a therapeutic setting, fairy tale characters can be interpreted as symbolic aspects of the self, enabling meaningful identification with various internal psychological themes [22].

Fairy tales can also function as transitional phenomena: they create distance from immediate reality and enable a symbolic engagement with inaccessible internal conflicts [28]. Their metaphorical language provides a protective space in which difficult topics can be explored symbolically and pictorially. In terms of content, they often address the concept of the “shadow” and the polarity of good and evil, representing fundamental human challenges [29].

The structure of fairy tales allows for symbolic engagement with biographical disruptions that may be difficult to access directly. Creative writing in this format gives patients the opportunity to narrate their lives and express the inexpressible from a safe distance. This can facilitate trauma integration and help build a coherent life narrative [6], [21].

Research on therapeutic writing shows positive outcomes overall, although results vary depending on the target population and timing of the intervention. Expressive writing, as developed by Pennebaker, can improve mental and physical health [10]. However, in trauma therapy it is often recommended to begin such interventions only after emotional stabilization has been achieved. Nevertheless, breast cancer patients who wrote about their experiences immediately after treatment experienced significant physical and psychological improvements [30]. The efficacy of narrative therapy techniques, particularly the transformation of distressing mental images, has also been confirmed [31], [32]. These methods support the integration of traumatic memories into coherent narratives, contributing to symptom reduction. Qualitative studies, such as those by Gisela Thoma (2012), also highlight how linguistic expression and narrative capacity can enable even fragmented trauma memories to be transformed into coherent and structured stories [21]. Two recent studies emphasize the value of narrative approaches in trauma processing. A demonstrated that autobiographically focused narrative interventions – such as Narrative Exposure Therapy – significantly reduce PTSD symptoms [31]. The integration of traumatic experiences into coherent life narratives is seen as a key mechanism. Furthermore, other authors highlight the importance of not only narrating but also understanding and integrating traumatic experiences into the self-concept. The so-called MERIT approach facilitates this by enhancing reflective abilities [33].

In summary, both therapeutic writing and narrative methods represent effective tools in trauma treatment, though further research is needed to determine optimal application conditions.

Against this background, psychotraumatology still lacks methods that enable emotionally relieving and, at the same time, resilience-promoting processing already during the therapeutic process – particularly on a symbolic and distanced level [11], [34]. Creative therapeutic approaches such as therapeutic writing or therapeutic work with fairy-tale symbolism are considered to have largely untapped potential in theory [11], [23]. Especially for patients with complex trauma, for whom confrontational or strongly emotion-focused approaches are (still) unsuitable, it is assumed that such methods can exert a stabilizing and resource-oriented effect [10], [21]. Combining biographical reflection, symbolic representation, and narrative transformation theoretically provides an approach that can offer structure and support processes of resilience promotion .

To operationalize resilience in this study, the BASIC Ph model by psychologist Mooli Lahad was used as an analytical framework. The model was developed by Lahad in the 1980s against the backdrop of recurring crises in his home country of Israel, in order to systematically record individual coping strategies for dealing with traumatic stress [35]. Based on earlier empirical studies [36] and the analysis of numerous other studies [34], he identified six basic coping strategies that people use in stressful and crisis situations:

- Belief (belief systems, values, meaning)

- Affect (expression of feelings, emotional processing)

- Social (social support, relationships, roles)

- Imagination (creative imagination, humour, symbolism)

- Cognition (rational understanding, problem solving, self-talk)

- Physical (physical expression, movement, action)

In the current research context, resilience is no longer understood as a stable personality trait, but as a dynamic, context-dependent, and lifelong adaptation process [37], [38]. It enables individuals to mitigate developmental risks, recover from stress, and build health-promoting skills [39].

The BASIC Ph model assumes that every person has an individual combination of these strategies, usually three to four, that shapes their personal way of dealing with stress [40], [35]. Therefore, it is therapeutically important to strengthen existing resources and specifically encourage neglected coping strategies.

The model is used worldwide in trauma, prevention, and emergency contexts—for example, in dramatherapy [41] or psychosocial care in crisis areas [42]. It serves both as a diagnostic tool for assessing individual coping profiles and as a means of evaluating interventions in terms of their resilience-promoting effects [35].

In this study, the BASIC Ph model was applied to examine the extent to which biographical fairy tale work activates resilience-promoting coping dimensions.

The aim of the present study was to examine the resilience-enhancing potential of a creative and distancing form of trauma processing – biographical fairy tale work – based on theoretical assumptions regarding the importance of narrative coherence, symbolic processing, and resource activation for fostering resilience. In this study, the BASIC Ph model was used as an analytical tool. The focus was on two research questions:

- How did the patient experience therapeutic writing as a creative therapeutic intervention?

- To what extent did the intervention contribute to promoting resilience?

Hypotheses:

- Biographical fairy tale work activates multiple coping strategies of the BASIC Ph model, particularly Affect, Belief, and Imagination.

- Biographical fairy tale work enables subjectively experienced emotional relief through symbolic distancing and narrative transformation.

- Biographical fairy tale work supports the development of narrative coherence, which contributes to a re-evaluation of distressing biographical experiences.

2 Methodology

2.1 Structure of the study

Our research approach was theory-driven and qualitative in nature, employing the study design of a qualitative case study in which causal relationships can be identified through direct and substantive correspondence between therapeutic intervention and observed effects in individual cases [43].

2.2 Data collection

Data were collected using a semi-structured, guided interview, with questions developed based on the six coping strategies of the empirically validated and internationally applied integrative coping and resilience model BASIC Ph by psychologist Mooli Lahad [40]. This was guided by existing literature [44], [45]. The interview was conducted in a specialist clinic for psychiatry, audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using qualitative content analysis according to Mayring [46]. The analysis followed systematic steps such as paraphrasing, generalization, and multi-stage reduction to form inductive categories. These categories were then compared with the theoretical BASIC Ph model to assess whether the six coping strategies (belief, affect, social, imagination, cognition, physical) were reflected in the findings.

The interview was conducted using a guide, and questions were carefully adapted for the instances where any problems with understanding occurred. A trusting atmosphere was ensured by the previous therapeutic process [46]. The interview was conducted in a non-judgmental manner and accompanied by empathetic but neutral listening [46].

2.3 Recruitment

The patient is a 39-year-old white German man with a completed commercial vocational education and a long-standing history of psychological difficulties beginning in childhood. He met the diagnostic criteria according to the ICD-10 for recurrent depressive disorder (F33), post-traumatic stress disorder (F43.1), and narcissistic personality disorder (F60.8). Despite long-term outpatient psychotherapy, his condition had significantly worsened in the 18 months prior to admission. He reported being overwhelmed by even short everyday activities, such as ten minutes of grocery shopping, and described needing up to four hours to get out of bed in the morning. His alcohol consumption had increased as a means of suppressing distressing memories, and he was no longer able to work.

The patient reported occasional suicidal thoughts, but without acute intent or planning. The main sources of distress were intrusive memories from childhood and a persistent sense of being controlled by his father. His stated therapeutic goal was to gain distance from these memories and develop a new view of himself.

Recruitment took place during an inpatient stay in a specialist psychiatric clinic in Southern Germany. Participation in the study was voluntary and occurred following comprehensive written informed consent, in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki [47]. The interview was conducted in the mother tongue of both patient and therapist (German) and later translated into English using DeepL Translator, version 4.9.

2.4 Intervention

The biographical fairy tale work was carried out in seven 50-minute sessions over a period of five weeks, with one to two therapeutic sessions per week. The procedure was discussed transparently and in detail with the patient. He was informed that he could withdraw his consent to participate in the single-case study and the interview at any time. One week after completion of the therapeutic process, a nine-minute interview was conducted.

In order to investigate the potential resilience-promoting effect of biographical fairy tale work with patients who have experienced trauma, a creative intervention was developed in five methodological steps:

- symbolic representation of the life-line,

- transformation of the biography into a fairy tale,

- creation of a positive ending (‘happy ending’) for the story,

- development of an ‘in-between’ stage between the current state of the fairy tale character and the happy ending,

- final reflection with transfer to one's own life.

With symbolic representation as a first step, the life story – including stressful experiences – was made visible in the room with the help of symbols. Natural materials (e.g., stones, shells), ropes, cloths, and figures (e.g., Schleich, Playmobil) were used. The method was based on systemic therapy approaches and narrative exposure therapy (NET), in particular working with the lifeline [8]. The objects used serve as transitional objects to make emotional content accessible [48]. The meaning of the symbols was left to the interpretation of the individual.

The focus was on biographical events that have shaped the individual’s life. The guiding question was: “What has shaped and influenced me, both positively and negatively?”

In this individual case, the patient’s biography – shaped by traumatic and memory gaps – was not presented in terms of objective accuracy but as a subjective narrative. The memory gaps themselves became part of the process and were integrated into the symbolic representation. The patient was encouraged to present his experiences independently of external perspectives.

If emotionally distressing content emerged during the process, a symbol was found for the memory, which was then integrated into the arrangement to externalize it and create emotional distance from the experience. Memories that emerged during the course of therapy were continuously integrated into the patient’s symbolic representation.

The therapist accompanied the process and ensured a chronological presentation. The symbolic arrangement was photographed after completion and then dismantled — the photograph served as an additional means of distancing and as a basis for further therapeutic work. Meaningful sections were then defined, resembling the chapters of a book.

The second step began with rewriting one's own life as a fairy tale. Based on the book chapters that have been created, a fairy tale was written in which one’s own experiences were symbolically processed. The story began with “Once upon a time...” and could be written down or told orally (with transcription by the therapist). The fairy tale ended with the main character in the middle of their current crisis.

In the third step, a positive ending (happy ending) was formulated, which offered a satisfactory, desirable conclusion for the main character of the fairy tale. In case of difficulties, it was possible to develop several positive endings.

In the fourth step, the “in-between” was told: What must happen to make a happy ending possible? What developments are necessary? This created a possible forward-looking part of the story [20], [21].

In the fifth step, the fairy tale was read aloud as a coherent story. The patient experienced themselves as both narrator and listener, which enables a change of perspective, emotional relief, and a reassessment of responsibility – especially in cases of parentification, neglect, or abuse. This can lead to significant relief in emotional experience [10], [11].

2.5 Integration of the BASIC Ph model into biographical fairy tale work

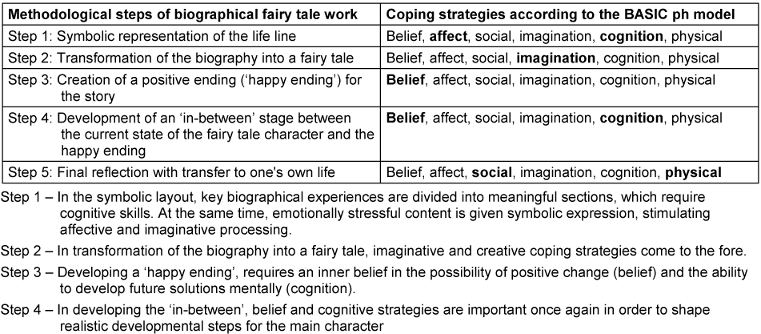

The coping strategies of the BASIC Ph model can be found in every step of biographical fairy tale work. On closer inspection, it becomes clear that although individual steps focus on specific strategies, all six coping dimensions are consistently considered and incorporated. The following Table (Table 1 [Tab. 1]) serves to illustrate this.

Table 1: BASIC Ph in biographical fairy tale work

2.6 Qualitative analysis and category system

The interview was evaluated using qualitative content analysis according to Mayring [46]. An inductive approach was chosen to avoid distortions caused by predefined concepts. After an initial paraphrasing and reduction of the statements, eight categories were formed, which were then combined into four main categories in a second analysis: Safety, emotion regulation, overwriting through a change of perspective, and complicating factors (complications). The last category was supplemented to adequately reflect stressful or inhibiting aspects of the process. The interview statements were systematically assigned to categories using a coding scheme with precise coding rules. In the interests of quality assurance, the quality criteria of qualitative research – transparency, rule-based approach and intersubjective traceability – were taken into account. These categories formed the basis for further analysis using the BASIC Ph model [49].

2.6 Observations

In addition to the semi-structured interview, clinical observations were made during the therapeutic sessions, with the therapist in the role of a participant observer. Following Mayring’s (2022) principles of open qualitative observation, these comprised non-verbal behaviour, interaction with symbolic materials, spontaneous remarks outside the interview prompts, and the development of the therapeutic relationship over the course of the intervention. Brief field notes were written immediately after each session. While these observations were not subjected to the formal qualitative content analysis of the interview data, they served as contextual supplements and captured process-related aspects that may not be fully reflected in the verbal accounts.

2.7 Application of the BASIC Ph model in the analysis

The coding system developed was examined for the occurrence of the six coping strategies of the BASIC Ph model. Classification was based on frequency and intensity using the categories ‘not represented’, ‘barely represented’, ‘strongly represented’ and ‘most strongly represented’.

The BASIC Ph model was then used to analyze the extent to which the therapeutic writing process activated specific resilience-related coping strategies. A detailed interpretation is provided in the results section.

2.8 Summary of the methodology

In biographical fairy tale work, personal experiences were transformed into a newly structured narrative form to open up meaningful and solution-oriented perspectives on one's own life story. The plot followed both the biographical events to date and the fairy tale's transformation structure, in which painful experiences are transformed. Central conflicts from the biography are symbolically represented and supplemented by healing, fairy tale-typical imagery, which is integrated into the story. This creates a future-oriented, conciliatory ending that is emotionally acceptable and can be integrated into the individual's self-concept and worldview. The intervention also draws on Jungian concepts by symbolically incorporating inner personality aspects into the narrative process.

3 Results

The results are presented in three parts: first, the main categories emerging from the qualitative content analysis; second, subjective and practical observations made during the intervention; and third, an analysis of resilience-promoting effects based on the BASIC Ph model.

The results are derived from a semi-structured interview, which was analyzed using qualitative content analysis and interpreted in relation to the BASIC Ph model. The analysis focused on two research questions:

- How did the patient experience therapeutic writing as a creative therapeutic intervention?

- To what extent did the intervention contribute to promoting resilience?

In addition to the interview analysis, observations gathered during the practical implementation of the intervention and subjective impressions were considered to illustrate the effectiveness and emotional impact of the biographical fairy tale work.

3.1. Results of the content analysis of the interview – development of main categories

From the inductive qualitative content analysis described above, the following main categories emerged: safety, emotion regulation, overwriting through a change of perspective, and difficulty. These aspects can be directly linked to the individual experience and processing of biographical content by the patient.

The category of safety describes the experience of structure, orientation, and emotional relief in the writing process. The patient particularly emphasized the opportunity to approach the past from a present, adult perspective without falling back into earlier emotional states. This form of stabilization is closely linked to the category of emotion regulation: the patient reported being able to regulate intense affective reactions and thereby develop new perspectives on significant others – especially his parents. Emotional distancing enabled more conciliatory attitudes and a deeper understanding of the past actions of others.

The category of overwriting through a change of perspective refers to the integration of new symbolic images that overlay or restructure existing memory patterns. These narrative techniques foster a reflective inner perspective and allow for a reorganization of self-image. The patient described being able to position himself within a role created from which new interpretations of his past became possible.

In contrast, the category of difficulty captures those aspects that made the process appear challenging. The need to abstract and visualize very personal or shame-laden content was experienced as emotionally and cognitively demanding. Nevertheless, in retrospect, the process was described as healing, with therapeutic support playing a central role [45].

3.2 Reflection on the practical approach

At the beginning, the patient needed support in selecting symbolic representations. As he became more confident, he took on more responsibility, while the therapist increasingly assumed a supportive role.

Working with biographical content was marked by anxiety and shame, especially with regard to his childhood, and triggered feelings of anger and helplessness. Initially, there were gaps in his memory, but as the process progressed, memories increasingly resurfaced and were symbolically integrated into the lifeline. The patient enjoyed telling fairy tales but initially needed an introduction to the principle of rephrasing. He was only able to achieve emotional distancing when he could find appropriate symbols, which then provided him with relief. He usually dictated his story to the therapist, placing great value on precise language.

3.3 Subjective observations in the therapeutic process

In addition to methodological reflection, subjective observations collected during the implementation are presented here. These observations are not included in the systematic evaluation but are intended to help illustrate the course and impact of the intervention.

It was easy for the patient to create a happy ending; he responded positively to this opportunity. His happy ending primarily reflected his desire for stable relationships. When applying the fairy tale to his own life, it became apparent that the opportunity to personally engage with his anger, injuries, and emotional wounds was deeply moving for him. He was able to view the protagonist of his story from an external perspective and recognize that the character was neither evil nor worthless, but part of a story that had not always gone in the protagonist’s favor. He succeeded in no longer viewing himself as a failure and was able to articulate what he wished for himself and his future life.

The relationship between the patient and the therapist became increasingly trusting and noticeably more relaxed as the sessions progressed. The patient appeared to feel less judged and more supported and was able to accept this support.

The observations made during the sessions are consistent with the statements expressed in the interview.

3.4 Resilience-promoting effects of biographical fairy tale work – a BASIC Ph-based analysis

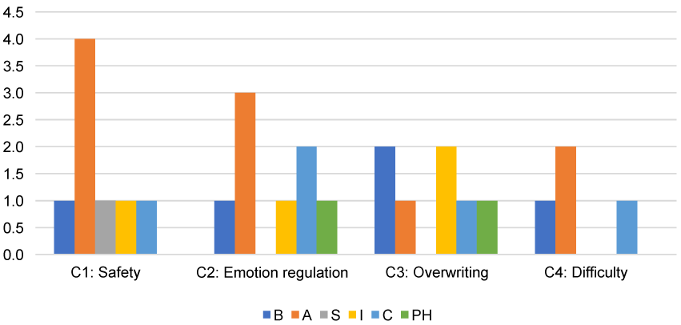

The results are summarized in Figure 1 [Fig. 1] and show that affect (A) is particularly strongly represented in all categories, while social (S) appears least frequently. A detailed interpretation of the results is provided in the next section.

Figure 1: Distribution of coping strategies in the BASIC-Ph model Note. Distribution of coping strategies in the BASIC-Ph model across the main categories of qualitative analysis, showing high representation of Affect (A) and low representation of Social (S) (own representation). Y-axis = frequency of occurrence; X-axis = main categories of qualitative analysis. Abbreviations: B = Belief, A = Affect, S = Social, I = Imagination, C = Cognition, P = Physical, C1–C4 = Categories 1–4

Building on the analyzed categories and their classification within the BASIC Ph model, the following section presents the central changes in autobiographical processing as well as resilience-enhancing effects resulting from the intervention.

In terms of self-experience, a clear shift became evident: the patient experienced himself more in his adult self, was able to re-evaluate guilt and shame, and develop distance from perpetrator figures. The narrative structuring of his life story made it possible to organize personal experiences within a meaningful framework. Despite memory gaps, a coherent, symbolically supported story emerged that included a beginning, middle, and end, forming a biographical whole. The omission of specific individuals from the narrative did not appear to impair its coherence. Rather, narrative techniques were used to functionally integrate these gaps. This suggests that narrative coherence can emerge even when certain real biographical elements are omitted – a potential avenue for further research.

Regarding the resilience-promoting effects of the intervention, assigning the categories to the six coping strategies of the BASIC Ph model [49] revealed that at least three, and up to six, strategies were activated per category. The most strongly represented strategy was affect, which highlights emotional expression and affective processing – both in content and method, such as through the creative writing process itself [40], [49]. Belief also appeared in all categories, emphasizing the importance of meaning-making in coping with distressing experiences. Cognition and imagination were equally present and were reflected in the symbolic processing and restructuring of the biographical narrative.

Physical was only occasionally present, for example in moments of physical relief (e.g. the release of tension), and did not play a central role. Social was the least frequently observed strategy, even though the process took place in a therapeutic setting. This may reflect the individualized nature of creative writing, which was experienced more as a protected, solitary process than as a socially embedded group activity.

Overall, the results indicate that biographical fairy tale work promotes resilience by addressing multiple coping strategies simultaneously. Particularly significant is the activation of affective and cognitive resources and the opportunity to reorganize autobiographical meaning.

4 Discussion

This case study shows that the patient experiences noticeable changes in self-perception, emotion regulation, and meaning-making. Over the course of the intervention, he reports greater emotional distance from distressing memories, increased narrative coherence, and a more future-oriented self-concept. The BASIC Ph analysis shows that several coping strategies are activated, particularly Affect, Belief, and Imagination, indicating a potential resilience-promoting effect.

The analysis shows that therapeutic writing in the form of biographical fairy tale work can have an integrative, structuring and resilience-promoting effect. By consciously creating symbolic, new images, patients are able to re-evaluate stressful experiences and place them in a meaningful context. This symbolic distancing allows them to reconsider biographical conflicts that were not possible to be reflected upon in their immediate experience. The fairy-tale element acts as a medium of alienation and makes it easier to bring emotional content into a workable form – comparable to rehearsing actions in the protected space of the narrative.

In the interview conducted by the author, the patient reports that with each new visual connection, a feeling of tension was released, indicating direct affective relief. Observational notes further describe the emergence of an inner orientation – the fairy tale serving as a symbolic “reference point” and structuring element that helps him view his biography in a new way.

According to the evaluation, the intervention activates several of the six coping strategies of the BASIC Ph model [49], particularly affect, belief and imagination. Emotional expression (affect) is not only evident as an accompanying phenomenon, but also as a central principle of creative writing, as Pennebaker and Chung [10] emphasize. The newly created meaning structure (belief) and the creative engagement with alternative perspectives (imagination) enable a symbolic integration of fragile memory fragments. Cognition and physical strategies play a supporting role, although the physical dimension does not play a central role. The social strategy appears to be less pronounced, although therapeutic support was essential for the process. Further research is needed to investigate how this individualized intervention relates to the social dimension of therapeutic settings.

This raises the question of whether a group situation or sharing the story with others could promote the social aspect more strongly. It would be useful to examine this variable specifically in future studies.

The results examined using the BASIC Ph model can also be interpreted in terms of therapeutic factors described in the Creative Arts Therapies literature. As De Witte et al. [50] and Feniger Schaal et al. [51] point out, relevant mechanisms include metaphor, distancing, perspective-taking, and playfulness, as well as embodiment and enactment. In the present intervention, metaphorical and symbolic elements were central. Distancing was fostered through the transformation of autobiographical material into symbolic form, enabling the patient to engage with traumatic content. Perspective-taking emerged through identification with the fairy-tale character and retelling the life story from that character’s perspective. Playfulness was reflected in the imaginative, creative aspects of the writing process, which allowed a less constrained exploration of possibilities. Embodiment was integrated through the physical arrangement and general handling of objects, while enactment was part of the re-structuring of the life story. These factors may have contributed to the observed changes and should be further investigated in future studies.

The major limitation of our qualitative case study is, that this work does not allow generalizable statements to be made about the effectiveness of the method. It provides a snapshot and can only help us generate hypotheses about possible effects or mechanisms of action. An increase in sample size and a control group design, would improve the level of evidence of results. A longer-term effect on the sense of sustainable change was not investigated; a longitudinal study would be necessary for this.

A methodological tension arises from the interdisciplinary combination of approaches from psychotraumatology, fairy tale research and creative therapy. The different scientific traditions and standards, in particular the contrast between quantitative-diagnostic psychotraumatology and the qualitative approach of arts therapies, were deliberately brought together. This can be seen as a critical point, but also as a strength of the study: complex, subjective change processes require a multi-perspective approach [52]. In addition, the interview was conducted by the same person who provided therapeutic support. This may have resulted in possible distortions due to social desirability or confirmation bias.

Despite these limitations, the case study provides valuable insights into subjective change processes through creative writing methods and opens up avenues for further research in the field of narration, resilience and therapy.

The results are consistent with theoretical assumptions about the importance of narrative integration in trauma therapy [6], [10]. Writing is experienced as a structuring and transformative process that integrates affect regulation and cognitive restructuring.

5 Conclusions

This case study illustrates that therapeutic writing in the form of biographical fairy tale work can be an effective creative therapeutic intervention for processing traumatic experiences. The patient of our analysis benefited from the method and described it as relieving, clarifying, and structuring. The combination of autobiographic reflection and symbolic transformation enabled the integration of inner conflicts into a new narrative framework. Several strategies of the BASIC Ph model were activated, in particular Affect, Belief, and Imagination – central dimensions for affect regulation, meaning-making, and creative processing of stressful experiences [10], [49]. The analysis points to the importance of a therapeutic framework that provides safety, relationship, and support. Creative writing alone would not be sufficient; attentive therapeutic support that enables distancing and self-efficacy is crucial. The symbolic alienation achieved through the fairy-tale setting creates a protected space in which new perspectives can be adopted and emotional tensions regulated.

At the same time, the study is subject to significant limitations: as a qualitative case study, it does not provide generalizable results, but rather a snapshot that helps generate hypotheses. We have no data of any long term effects, that would let us estimate how sustainable the results are. Furthermore, the therapist’s and researcher’s role were combined in one person, which may have introduced confirmation bias and social desirability.

Regarding the research questions, the following conclusions were drawn:

- The patient experienced therapeutic writing as emotionally relieving, structuring and identity-strengthening. The symbolic restructuring of his life story enabled new perspectives onto himself and his past.

- The intervention activated several coping dimensions of the BASIC Ph model, particularly in the area of affective and cognitive processing. This indicates resilience-promoting effects in a subjectively meaningful context.

The results are consistent with previous findings on the effects of expressive writing [53] and narrative-oriented forms of therapy. A future comparison with methods such as Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) [8], [54], which use similar structuring processes but without symbolic, alienating fairy tale elements, seems useful. Biographical fairy tale work could represent an innovative addition to the spectrum of creative trauma therapy.

In practice, writing has been shown to be a resource-oriented method that not only processes trauma but also reconnects it to a coherent life context. Further studies – ideally controlled, fully-powered, long-term research designs – are needed to systematically test the effectiveness of the method.

In addition, biographical fairy tale work has further methodological potential beyond the medium of writing: its symbolic-narrative structure can also be integrated into other creative forms of therapy, such as drama therapy, in which body expression, role-playing, and staging, open up further dimensions of experiences and therapeutic benefit. Fairy tale work can be further developed under the aspect of embodiment in order to integrate somatic resonance and affective experience more strongly. In this way, the method can be established as an overarching concept in creative therapeutic procedures and be used effectively in various settings, either individually or in groups.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The authors were responsible for the conception, design, implementation, analysis, and writing of this study. The study was part of the first author’s Master’s thesis. Particular roles: Study design: K.R.; delivery of drama therapy: K.R.; statistical analyses: K.R; drafting

of manuscript: KR.; critical revision: C.V., J.J., S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

The qualitative data collected in this study (interview transcript) contains personal and sensitive information and is therefore subject to data protection regulations. As such, they cannot be made publicly available. Access to anonymized excerpts may be granted upon reasonable request, provided that ethical and data protection requirements are met.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participant gave written informed consent. All data were anonymized and handled confidentially.

Funding

The project underlying this report (the publication) was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research under the funding code 03FHP207. Responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating patient for his openness and trust, as well as the clinical team for their support during the implementation of the intervention.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material related to this article (e.g., interview guide, intervention outline) is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Fischer G, Riedesser P. Lehrbuch der Psychotraumatologie. 5., aktualisierte und erweiterte Aufl. Stuttgart: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag; 2020. DOI: 10.36198/9783838587691[2] Maercker A. Trauma und Traumafolgestörungen. München: C.H. Beck; 2017. DOI: 10.17104/9783406698514

[3] Maercker A, Eberle DJ. Was bringt die ICD-11 im Bereich der trauma- und belastungsbezogenen Diagnosen? Verhaltenstherapie. 2022;32(3):1-10. DOI: 10.1159/000524958

[4] Schörmann C. Biografiearbeit mit traumatisierten Menschen: Perspektiven aus der Sozialen Arbeit. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa; 2021.

[5] Muenzenmaier K, Schneeberger AR, Castille DM, Battaglia J, Seixas AA, Linke B. Stressful childhood experiences and clinical outcomes in people with serious mental illness: a gender comparison in a clinical psychiatric sample. J Fam Viol. 2014;29(4):419-29. DOI: 10.1007/s10896-014-9601-x.

[6] van der Kolk BA. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Penguin Books; 2015.

[7] Tani F, Smorti M, Peterson C. The words of violence: Autobiographical narratives of abused women. J Fam Violence. 2016;31:885-96. DOI: 10.1007/s10896-016-9824-0

[8] Neuner F, Schauer M, Elbert T. Narrative Exposition. In: Maercker A, editor. Posttraumatische Belastungsstörungen. 4th ed. Berlin: Springer; 2013. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-35068-9_18

[9] Pohl R. Das autobiographische Gedächtnis: die Psychologie unserer Lebensgeschichte. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer; 2007. DOI: 10.17433/978-3-17-029542-1

[10] Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing, emotional upheavals, and health. In: Friedman HS, Silver RC, editors. Foundations of health psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 263-84. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780195139594.003.0011

[11] Heimes S. Kreatives und therapeutisches Schreiben – Ein Arbeitsbuch. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; 2015. DOI: 10.13109/9783666404696

[12] Petzold H, Orth I. Poesie und Therapie: Über die Heilkraft der Sprache; Poesietherapie, Bibliotherapie, literarische Werkstätten. Unveränderte Neuauflage. Bielefeld: Aisthesis; 2005.

[13] Unterholzer CC. Selbstwirksam schreiben: Wege aus der Rat- und Rastlosigkeit. Heidelberg: Carl-Auer; 2021.

[14] Haußmann R, Rechenberg-Winter P. Alles, was in mir steckt: Kreatives Schreiben im systemischen Kontext. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; 2013. DOI: 10.13109/9783666462665

[15] Werder Lv. Lehrbuch des kreativen Schreibens: Grundlagen - Technik - Praxis. Wiesbaden: Marix; 2007.

[16] Ruf O. Kreatives Schreiben: Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag; 2016. DOI: 10.36198/9783838536644

[17] Vopel KW. Schreiben als Therapie: Ein Handbuch. Salzhausen: Iskopress; 2014.

[18] Miethe I. Biografiearbeit: Lehr- und Handbuch für Studium und Praxis. 3rd ed. Weinheim: Beltz; 2017.

[19] Sack M. Schonende Traumatherapie: ressourcenorientierte Behandlung von Traumafolgestörungen. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 2010.

[20] Carr A. Michael White's narrative therapy. In: Carr A, editor. Clinical Psychology in Ireland, Vol 4, Family therapy theory, practice and research. Lewiston (NY): Edwin Mellen Press; 2000. p. 15-38.

[21] Boothe B, Thoma G. Die Erzählbarkeit des Traumas. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; 2012

[22] Pöge-Alder K. Märchenforschung: Theorien, Methoden, Interpretationen. 3rd ed. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attemptor; 2016. (narr Studienbücher).

[23] Kast V. Märchen als Therapie. 15th ed. München: dtv; 1993.

[24] Abfalter I. Märchen in der Therapie: Warum sich Märchen für die psychotherapeutische Arbeit eignen und wie man sie einsetzt. Saarbrücken: AV-Akademikerverlag; 2014.

[25] Röhrich L. "und weil sie nicht gestorben sind..." – Anthropologie, Kulturgeschichte und Deutung von Märchen. Köln: Böhlau; 2002.

[26] Sindelar B. Märchen und Individualpsychologie. In: Rieken B, editor. Erzähltes Minderwertigkeitsgefühl: Individualpsychologie in volkskundlicher Erzählforschung und Literaturwissenschaft. Münster: Waxmann; 2022. p. 33-54.

[27] Kaya TAK, Kahlau H. Praxisbuch Lebendige Biografiearbeit mit Märchen. Weinheim: Beltz; 2021.

[28] Winnicott DW. Vom Spiel zur Kreativität. 13. Aufl. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta; 2012.

[29] Kast V. Der Schatten in uns: Die subversive Lebenskraft. Neuauflage der 5. Aufl. von 1999. Stuttgart: Patmos; 2018.

[30] Henry EA, Schlegel RJ, Talley AE, Molix LA, Bettencourt BA. The feasibility and effectiveness of expressive writing for rural and urban breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010 Nov;37(6):749-57. DOI: 10.1188/10.ONF.749-757. PMID: 21059586.

[31] Raeder R, Clayton NS, Boeckle M. Narrative-based autobiographical memory interventions for PTSD: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychol. 2023 Sep 27;14:1215225. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1215225. PMID: 37829075; PMCID: PMC10565228.

[32] Holmes EA, Arntz A, Smucker MR. Imagery rescripting in cognitive behaviour therapy: images, treatment techniques and outcomes. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;38(4):297-305. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.007. Epub 2007 Oct 26. PMID: 18035331.

[33] Wiesepape CN, Smith EA, Muth AJ, Faith LA. Personal Narratives in Trauma-Related Disorders: Contributions from a Metacognitive Approach and Treatment Considerations. Behav Sci (Basel). 2025 Jan 30;15(2):150. DOI: 10.3390/bs15020150. PMID: 40001781; PMCID: PMC11851491.

[34] Lahad M, Leykin D. The Integrative Model Of Resiliency: The "BASIC Ph" Model, Or What Do We Know About Survival? In: Ajdukovic D, Kimhi S, Lahad M, editors. Resiliency: Enhancing Coping with Crisis and Terrorism. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2015. p. 71-91. DOI: 10.3233/978-1-61499-490-9-71

[35] Lahad M. From victim to victor: The development of the BASIC PH model of coping and resiliency. Traumatology. 2017;23(1):27-34. DOI: 10.1037/trm0000091

[36] Lahad M, Abraham A. Coping and resiliency: The BASIC Ph model. Community Stress Prevention. 1983;1:55-60.

[37] Fooken I. Psychologische Perspektiven der Resilienzforschung. In: Wink R, editor. Multidisziplinäre Perspektiven der Resilienzforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer; 2016. p. 12-46. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-658-09623-6_2

[38] Schellong J, Epple F, Weidner K. Praxisbuch Psychotraumatologie. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2018. DOI: 10.1055/b-006-149613

[39] Laucht M. Vulnerabilität und Resilienz in der Entwicklung von Kindern. In: Brisch KH, Hellbrügge T, editors. Bindung und Trauma: Risiken und Schutzfaktoren für die Entwicklung von Kindern. 7th ed. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta; 2012. p. 63-78.

[40] Lahad M, Shacham M, Ayalon O. The "BASIC Ph" model of coping and resiliency - theory, research and cross-cultural application. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2013.

[41] Jennings S. The handbook of dramatherapy. Abingdon-on-Thames: Psychology Press; 1994.

[42] Lahad M, Doron M. Protocol for treatment of post traumatic stress disorder. In: NATO Science for Peace and Security Series - E: Human and Societal Dynamics. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2010. DOI: 10.3233/978-1-60750-575-4-i

[43] Kiene H. Komplementäre Methodenlehre der klinischen Forschung. Berlin: Springer; 2001. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-59445-8

[44] Hopf C. Qualitative Interviews: Ein Überblick. In: Flick U, von Kardorff E, Steinke I, editors. Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch. 13th ed. Hamburg: Rowohlt; 2005. p. 349-59.

[45] Misoch S. Qualitative Interviews. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 2015. DOI: 10.1515/9783110354614

[46] Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. 13th ed. Weinheim: Beltz; 2022. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-658-37985-8_43

[47] World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013 Nov 27;310(20):2191-4. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

[48] Wollschläger ME, Wollschläger G. Der Schwan und die Spinne: das konkrete Symbol in Diagnostik und Psychotherapie. Bern: Hans Huber; 1998.

[49] Lahad M. Creative supervision: The use of expressive arts methods in supervision and self-supervision. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1997.

[50] de Witte M, Orkibi H, Zarate R, Karkou V, Sajnani N, Malhotra B, Ho RTH, Kaimal G, Baker FA, Koch SC. From Therapeutic Factors to Mechanisms of Change in the Creative Arts Therapies: A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2021 Jul 15;12:678397. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397

[51] Feniger-Schaal R, Constien T, Orkibi H. Playfulness in times of extreme adverse conditions: a theoretical model and case illustrations. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 2024 Dec;11(1):1446. DOI:10.1057/s41599-024-03936-z.

[52] Flick U, von Kardorff E, Steinke I. Was ist qualitative Forschung? Einleitung und Überblick. In: Flick U, von Kardorff E, Steinke I, editors. Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch. 12. Aufl. Hamburg: Rowohlt; 2017. p. 13-29.

[53] Pennebaker JW. Heilung durch Schreiben: Ein Arbeitsbuch zur Selbsthilfe. 2. unveränderte Aufl. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2019. DOI: 10.1024/85976-000

[54] Schauer M, Elbert T, Neuner F. Narrative Exposure Therapy: A Short-term Treatment for Traumatic Stress Disorders. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2011.