“I matter too!” – The effect of the drama therapy self-image module on clients with a personality disorder and low self-esteem: an experimental multiple baseline single case study

Marieke H. Mulder 1Gerben J. Westerhof 2

1 Mediant GGz, Enschede, The Netherlands

2 University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

Abstract

Background: Low self-esteem is a major problem in people with a personality disorder. This study examined the effect of the protocolised drama therapy self-image module (DSIM) on the self-esteem and well-being of these clients. We also investigated how participants experienced the module.

Method: Within a multiple baseline single case experimental design, eleven participants (n=11) with a personality disorder and low self-esteem were scored weekly on the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale and the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form before, during and following participation in the module. The module consisted of six weekly 75-minute group sessions. Eight participants (n=8) were interviewed about their experiences with the module.

Results: Self-esteem and well-being increased during and following participation in the module. A significant improvement could also be seen at group level. The interviews showed that participants appreciated the module, although they perceived it as too short.

Conclusion: The results suggest that the module is likely to contribute to increases in self-esteem and well-being in clients with a personality disorder. These results seem to justify adding the module to the standard therapy programme for these clients. The results are tentative because the effect of the module was not compared with that of a control intervention. Future research may shed more light on this.

Keywords

drama therapy, personality disorders, self-esteem, MultiSCED, interview

Introduction

Low self-esteem is common in people with personality disorders. Explicitly attending to this can potentially contribute to the quality of treatment. Within the field of drama therapy, Hilderink [1] developed the drama therapy self-image module (DSIM). This is a short-term module, usually offered in groups, in which interventions from, in particular, drama therapy are used to improve self-esteem. In this article, we will examine the effect of the drama therapy self-image module on clients with a personality disorder.

Self-esteem, in common parlance often referred to with the less clearly defined term ‘self-image’, is usually understood as the feeling of being ‘good enough’. In this context, we define it, based on Orth and Robins [2], as a person’s subjective, global judgement of his or her own worth as a person. Self-esteem is a component of self-concept, (sometimes also referred to as ‘self-image’), which also contains other components, such as self-knowledge and the extent to which a person perceives him/herself as delimited from others [3].

Low self-esteem is related to various psychological symptoms, like depression and automutilation [4], [5], [6] it is considered a transdiagnostic factor [7]. The question is whether low self-esteem makes people vulnerable to psychological complaints (the vulnerability hypothesis) or whether psychological complaints leave lasting changes in self-esteem (the scar hypothesis). Sowislo and Orth [3] performed a meta-analysis of the relationship between self-esteem and depression. They found evidence that supports the vulnerability hypothesis, i.e. that low self-esteem causally contributes to depression.

Self-esteem is not exclusively related to psychological problems and complaints, but also to positive functioning. For example, high self-esteem correlates strongly with some components of well-being [8], but not all of them: therefore well-being is more comprehensive than self-esteem. In a review, Orth and Robins [2] discovered a causal relationship between self-esteem and success in work, relationships and (mental) health, matters that are partly related to well-being. Baumeister et al. [9] and Zeigler-Hill [10] warn against uncritically increasing self-esteem without considering the need to do so. However, the fact that the critical review by Baumeister et al. [9] supports correlations between low self-esteem and depression and between high self-esteem and happiness emphasises the relevance of self-esteem for mental health.

Low self-esteem is a common problem in people with a personality disorder. In general, self-concept (of which self-esteem is a part) is one of the areas in which people with a personality disorder encounter problems [11]. Thus, the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorders [12] explicitly considers self-esteem and self-worth in determining the level of personality functioning [13], [14]. Empirical research also shows a relationship between personality pathology and low self-esteem, particularly in clients with a borderline personality disorder or an avoidant personality disorder [15], [16], [17].

In treatments for personality disorders, the topic of self-esteem is not always explicitly touched upon. Therapists usually hope that a client’s self-esteem will increase as the diagnosed disorder is treated [18]. Whether this is indeed the case is up for debate. Korrelboom [19] identifies self-image (of which, in this context, self-esteem is the main component) as one of the most important cognitive or behavioural issues to address when treating clients with personality problems. After all, negative core thoughts about the self-play an important role in their pathology [19]. Korrelboom, Marissen and Van Assendelft [18] note that symptom-focused treatment seems to have little effect on self-esteem in patients with a personality disorder. They thus believe that low self-esteem must be explicitly targeted in treatment. In contrast, Roepke et al. [20] suggested in a study that self-esteem increases with Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) – a form of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) – in clients with a borderline personality disorder. Katsakou et al. [21] asked clients with a borderline personality disorder what they considered important goals of therapy. The answers most often given were: developing self-acceptance, self-confidence and self-esteem.

There are several methods for improving self-esteem. Fennell [22] designed a method mainly based on CBT. Korrelboom [19] discusses the distinction between cold cognitions (‘knowing that’) and hot cognitions (‘feeling that’). Cold cognitions refer to information contained in language, while hot cognitions pertain to the holistic, intrinsic, non-verbal information that can be activated and changed with experiential techniques. Particularly in clients with a personality pathology, hot cognitions play a significant role [16], [20]. In Competitive Memory Training (COMET), a training aimed at improving self-esteem, Korrelboom, Marissen and Van Assendelft [18] build on CBT, adding the elements of body posture and music that the client associates with his or her own strengths. In doing so, they aim to modify hot cognitions. Hilderink [1] developed the drama therapy self-image module (DSIM), which uses even more experiential techniques, drawn from drama therapy.

Drama therapy, like other arts therapies, is a treatment that emphasises direct experience and doing, and is less focused on talking. As such, it is aimed at hot cognitions [23]. In general, arts therapies use a ‘bottom-up’ approach: moving from basic processes such as physical perception to higher processes such as cognition [24]. Therefore, this type of therapy is primarily focused on hot cognitions. Various theories exist about the functional mechanisms of drama therapy in particular [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. In this context, elements often mentioned in the literature are the direct emotional bodily experience, the playful nature, working with role-play, and the presence of and interaction with audiences (in drama therapy groups usually part of the group).

Relatively little scientific research has been done on the effectiveness of drama therapy in general [30]. A review of research into drama therapy [31], exploring 89 different studies, shows that a multitude of methods and techniques have been examined in very diverse populations, using varying outcome measures. No specific intervention, population or context presents an abundance of empirical evidence for its effectiveness [31]. A recent review [32] shows progression in drama therapy research. The research confirms the effectiveness of drama therapy for various target groups and in various settings. In a review concerning the mechanisms of change in arts therapies, De Witte et al. [33] found some therapeutic factors unique to all creative arts therapies, like embodiment, concretization and symbolism. Concerning drama therapy, the authors concluded that the literature identifies therapeutic factors that need further operationalisation. This may have to do with the fact that drama therapy is widely branched in terms of both theory and practice. The present study illustrates this: it concerns only one specific module within the broad spectrum of drama therapy interventions.

Two articles focused on personality disorders. Keulen-de Vos et al. [34] conducted a pilot study of a protocolised form of drama therapy in a forensic clinic with perpetrators of violent sexual crimes with a cluster B personality disorder (antisocial, narcissistic, histrionic or borderline personality disorder). They found that this therapy contributed to an increase in vulnerable feelings rather than anger during the sessions. Because of the tendency in this population to emotionally withdraw, to suppress any kind of vulnerability, and to be hostile, this is a promising effect. In a pilot study, Doomen [35] examined the effect of schema focused drama therapy on clients with a cluster C personality (avoidant, obsessive-compulsive and dependent personality disorders) and found promising results with regard to dealing with emotions and coping, among other things.

The drama therapy self-image module (DSIM) is a short-term module that is applied in groups to improve the participants’ self-image, in particular their self-esteem. This module mainly uses drama therapy elements such as role-play, role-change, scene work and rescripting. In addition, the module applies cognitive-behavioural interventions, especially as part of the homework assignments. This module is the object of this current study. Hilderink [36] discovered in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) that the DSIM is effective in a clinical setting for clients with anxiety disorders. This study examines for the first time the effect of the DSIM on clients with a personality disorder, in an outpatient setting.

It investigates the efficiency of the module in clients with a personality disorder as the main diagnosis, who are indicated for outpatient treatment by specialist mental health services. The knowledge derived from it may provide insights that contribute to optimising the treatment of low self-esteem in clients with a personality disorder and could perhaps facilitate a more targeted use of drama therapy in general.

Our research question is: what is the effect of the DSIM on the self-esteem and, subsequently, on the well-being of clients with a personality disorder? We also examined how clients experienced the DSIM.

Based on the above, we formulated the following hypotheses:

- DSIM leads to an increase in self-esteem during and following the intervention when compared to the baseline established during waiting time and/or psychoeducation.

- DSIM leads to an increase in well-being during and following the intervention when compared to the baseline established during waiting time and/or psychoeducation.

Method

Design

The study was partly quantitative (n=11), and partly qualitative (n=8) in nature. We adopted a multiple baseline single case experimental design for the quantitative part. This design provides practical and valid ways to empirically validate interventions and is closely tied to clinical practices [37], [38]. It is considered a possible alternative to RCT [39], but needs far less participants (even as few as three) as the many measurement points per subject allows each participant to serve as its own control [40]. Eleven participants completed weekly measurement questionnaires during baseline, the DSIM and afterwards. The primary outcome measure is the progression of developing self-esteem and well-being before, during and following the module. Participants registered to take part in the study at various times. The module could not be started until there was a group of at least three participants. Because measurements were started as soon as a participant was included, the number of pre-measurements varied from two to fifteen. Four participants received psychoeducation on schema focused therapy during the pre-measurements. The number of measurements during the module ranged from two to six. All participants were subject to three follow-up measurements.

For the qualitative part of the study, eight participants were interviewed about their experiences with the module.

The study protocol (number NL66011.044.18) was approved by the Twente Medical Ethics Review Committee and was registered in the Dutch Trial Register under number NL7060.

Setting and sample

The study took place at De Boerhaven, a centre of expertise for personality disorders at Mediant GGz. Adults between the ages of eighteen and sixty who have been diagnosed with a personality disorder are treated here.

The inclusion criteria were:

- low self-esteem (Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES) ≤27),

- diagnosed with a personality disorder as the main diagnosis,

- willing and able to attend group treatment,

- indicated for outpatient schema focused therapy (SFT), and

- still in the preparatory phase of schema focused therapy. In this phase, clients receive psychoeducation about schema focused therapy and, if necessary, individual supportive counselling. Clients took part in psychoeducation prior to or during the pre-measurements.

Of these, the first inclusion criterion was checked by the researcher by scoring the client on the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES), the others by the intake worker and intake staff, who also checked the exclusion criteria.

The module was studied in the period between psychoeducation on schema focused therapy and the start of SFT. Where possible, psychoeducation was offered as part of the pre-measurements.

Exclusion criteria were:

- current suicidality,

- mental disability,

- active substance abuse or addiction,

- seriously aggressive behaviour,

- a Cluster A– (schizoid, schizotypal, paranoid or antisocial) personality disorder.

Sample

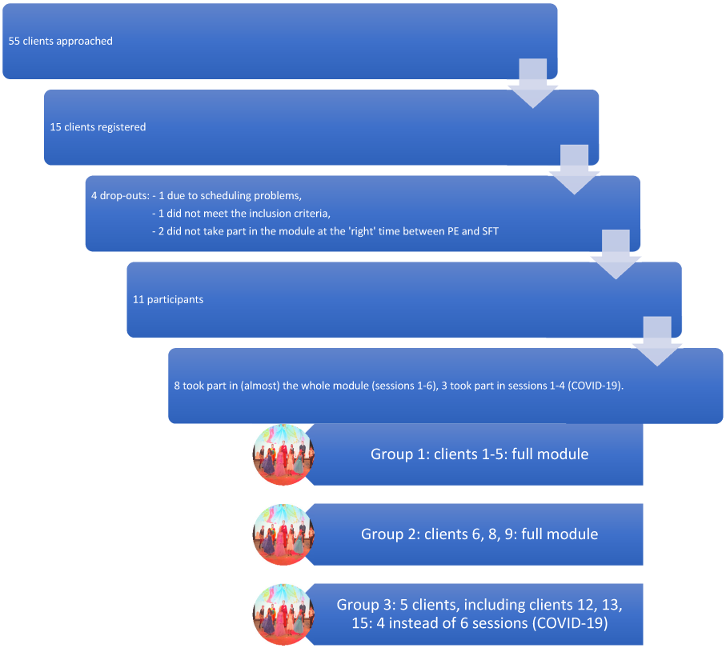

The aim was to include ten clients. As shown in Figure 1, fifty-five clients were approached to take part in the study (n=55). Of these, fifteen clients registered to participate. Of these, four dropped out (client 7, client 10, client 11 and client 14): one because of a failure to meet the inclusion criteria, one because of difficulties in scheduling group sessions, and two because the order of psychoeducation, the DSIM and schema focused therapy was different from the procedure described beforehand. The latter two clients took part in the module (in the last group), but not in the study. The eleven participants started the module in three consecutive groups of 5, 3 and 5 clients, respectively, between May 2019 and March 2020. The latter group was only able to attend four of the scheduled six sessions due to COVID-19 measures: because of the need of social distancing, all group therapies stopped in March 2020. Data collection was discontinued after the usual number of follow-up measurements. Participants were given the opportunity to attend the last two sessions at a later date.

Thus, of eleven participants (n=11), eight took part in the entire module and completed sufficient measurement questionnaires (n=8). Three participants were unable to complete the module due to COVID-19 measures. Schematically, see Figure 1 [Fig. 1].

Of the eleven participants, ten were women and one was a man. All participants were Caucasians. The age of the participants ranged from 22 to 55 (M=37.2, SD=10.6). Four of the 11 participants were highly educated (≥15 years of education). Nine participants had been diagnosed with an „other specified personality disorder“, which is by far the most common DSM-5 classification in terms of personality disorders. One participant was classified as having a borderline personality disorder, another one as having an avoidant personality disorder. Total scores on the BSI range from 0.57 to 3.09 with a mean of 1.46 and a median of 1.25. This is somewhat higher than the average of 1.23 among patients found by De Beurs and Zitman [41]. Severity Indices of Personality Problems (SIPP) scores were compared with the norm group of psychiatric patients. Three participants (clients 5, 6 and 13) scored low on one or two domains and average on the others. The other nine participants scored average to high on all domains.

Intervention

Clients were offered to participate in the drama therapy self-image module (the DSIM), led by a drama therapist. This is a protocolised group-based module aimed at improving self-esteem, consisting of 6 sessions of 75 minutes each, with homework assignments in between sessions.

Session one includes an explanation of self-esteem and self-image and their relationship to each person’s personal history, as well as a group discussion on negative experiences related to low self-esteem. Clients take turns showing the group how they try to hide their low self-esteem from others in an exercise in which they take turns walking on a catwalk. The homework assignment for the next session is to write down one’s own ‘negative self-image’ (meaning the cognitions about themselves that underlie their low self-esteem).

In session two, each client reads out their ‘negative self-image’ text (the cognitions underlying low self-esteem). A neutral scene is role-played by two clients, during which each has a fellow client voicing their internal criticism. A tableau vivant (a scene presented by client and/or group members who remain silent and motionless as if in a picture) is created depicting how the client experiences himself or herself and his/her environment. The homework assignment for the next session is to have significant others read the ‘negative self-image’ text (the cognitions underlying low self-esteem), to ask for their feedback, and to list positive traits.

In session three, starting from the ‘negative self-image’, clients describe an alternative ‘positive self-image’ (i.e. cognitions that may underlie higher self-esteem) and refine this into a ‘realistic self-image’ (i.e. cognitions that may underlie realistic self-esteem). Role-playing is used to practise dealing with criticism.

The homework assignment for next session is to bring music that supports a ‘more positive self-image’ (i.e. the cognitions underlying higher self-esteem), and to find two pieces of evidence for a more positive self-image.

In session four clients again walk down a catwalk, this time using the perspective of a ‘more positive self-image’. A role-play is performed: a scene in which the positive self-image is confirmed. The homework assignment for next session is for the clients to make a ‘positive self-esteem’-flashcard (i.e. write down the cognitions belonging to higher self-esteem on an easy-to-carry card) and to take that card with them at all times. The positive self-image is practised daily in front of a mirror. This means that the thoughts associated with higher self-esteem are expressed with corresponding body posture and intonation. The client thinks about a situation in which the ‘negative self-image’ was created or through which it is maintained.

In session five, a rescripting of a negative experience takes place, using the doubling technique. In this technique, a group member or the therapist stands by to the protagonist and resonates with the protagonist while staying in touch with his/her own emotions. In this exercise, the protagonist first plays an experience linked to the ‘negative self-image’. A group member can play a doubling role. Then, the doubling group member plays the situation. Subsequently, the protagnonist is asked to replay the situation from the perspective of the positive self-image. The homework assignment for next session is for clients to make, buy or do something nice for themselves. A list is made of triggers that usually invoke a ‘negative self-image’.

In session six, adequate coping with a frightening or difficult situation (a situation that usually triggers a ‘negative self-image’) is practised using imagination techniques. Finally, the module is evaluated.

The DSIM was always led by the same drama therapist, who was trained in the DSIM and also received supervision with regard to the DSIM. She was not involved in the study. A graduate student in psychology once observed a random session to ensure therapy integrity: no deviations from the protocol were found.

Measuring tools

Self-esteem was measured using the Dutch translation of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES), a globally used questionnaire measuring explicit global self-esteem [42]. This questionnaire is also used in clinical populations. The RSES consists of ten questions that can be answered on a 4-point Likert scale. The minimum score is 10, the maximum score is 40: the higher the score, the higher the self-esteem. The mean score in the Netherlands is 31.6 with a standard deviation (SD) of 4.5 [43]. Its reliability is good [44] as are its convergent and divergent validity [43]. The psychometric aspects of its Dutch translation are good [45]. Everaert et al. (2010) [46] reached similar findings in a clinical population in the Netherlands. They found an average score among clients of 23.9. In studies by Korrelboom [18] and Hilderink [36] on the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing self-esteem, the RSES was found to be sensitive to change. Korrelboom [18] sets the threshold between healthy and unhealthy self-esteem at a mean score of 28. Therefore, in this study, the upper limit to take part in the module is an RSES score of ≤27.

Well-being was measured using the Dutch version of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). This questionnaire consists of 14 questions. Respondents score the frequency of their feelings on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “(almost) daily”. The questionnaire covers three dimensions: emotional, psychological and social well-being. For the purpose of this study, the total score was used. The higher the score, the higher the level of well-being. The mean total score in the Dutch general population is 2.98, with an SD of 0.85 [47]. Van Erp Taalman Kip and Hutschemaekers [48] found a mean score among outpatients in the Netherlands of 2.07. The questionnaire was found to be reliable (Cronbach’s alpha 0.89). Its convergent and divergent validity are good and it is sensitive to change [47], [41].

In this study, total scores on the brief symptom inventory (BSI) [49] and domain scores on the severity indices of personality problems (SIPP), [50] were included in the description of participants during intake.

Finally, we explored participants’ experience of the aspects of the intervention that, in their perception, helped them to change and the aspects of the intervention that prevented change. These experiences were examined using the Change Interview [51], [52], [53], a semi-structured interview. The interviewers (the first author and a graduate student in psychology) were not involved in the module. Each individual participant was asked about her general experience of the module, the changes she noticed since participation in the module, the importance of the changes, the extent to which she expected the changes and the extent to which she thought the change had occurred without the module. The participants were also asked about helpful and problematic aspects and missing elements in the module.

Data analysis

Quantative analysis

RSES and MHC-SF scores were plotted in graphs for each participant. A first visual inspection of each participant was performed by roughly estimating level, trend and variation within and between conditions [54]. Subsequently we calculated for each participant mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) in the different phases of participation: during baseline, during the DSIM, and afterwards.

The data were analysed statistically at group level. Multilevel analysis (a complex form of analysis of variance, commonly used for this research design [55]) was used for this purpose. As part of this analysis, the data are structured hierarchically. In this study, the data were categorised first by client, then by phase (before or after the start of the intervention) and finally by measurement moment. Different numbers of measurements do not form a problem in this analysis. Outcomes are corrected for the interdependence of the data (autocorrelation). The multilevel analysis was performed in R using MultiSCED, developed by Declercq et al. [56]. This is a tool for analysing single case experimental data with multilevel modelling. In this analysis, we performed a second-level analysis across cases where condition 0 (baseline) was contrasted with condition 1 (measurements during and following the DSIM). While the N seems to be low for a multilevel analysis, Declercq et al. confirm that such analyses could be performed starting with an N of 3 [56].

Qualitative analysis

Following the module, Change Interviews were conducted with the eight participants who took part in the entire DSIM. The interviews were recorded on a dictaphone. Subsequently these interviews were transcribed by the first author, and after that analysed by her as well. This involved first reading the transcripts in their entirety, then identifying keywords per question (across all participants) that formed the basis for categories that were subsequently devised. The results were then compared with the theory on drama therapy described in the introduction.

Results

Answering the questions: quantitative

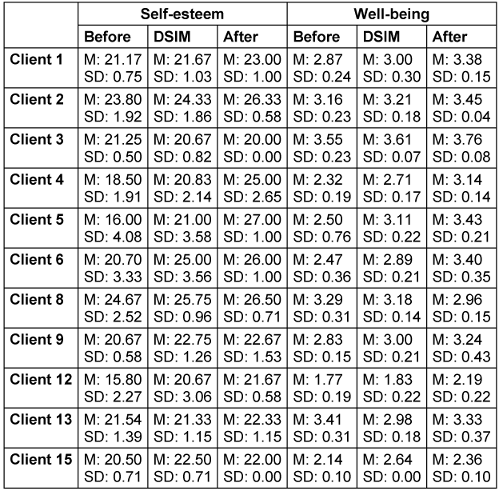

To examine the progression of developing self-esteem (RSES) and well-being (MHC-SF) before, during and following the DSIM, we plotted the quantitative data in graphs and visually inspected them. Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of the scores in self-esteem (RSES) and well-being (MHC-SF) were calculated for each participant for each phase during baseline, during the DSIM and afterwards. The results are detailed in Table 1 [Tab. 1].

Table 1: Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of the scores in self-esteem (RSES) and well-being (MHC-SF) before DSIM, during DSIM and afterwards (clients 7, 10, 11 and 14 were not included in the study)

These results suggest that for some participants, there is a clear improvement in self-esteem and/or well-being. Most participants seem to have a modest improvement in self-esteem and well-being over time. A few participants, however, seem to deteriorate slightly over time.

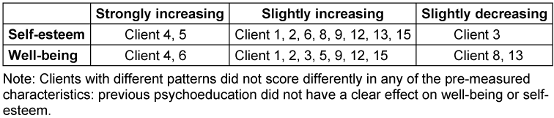

Looking more closely, we could define 3 groups:

- participants with strongly increasing scores (at least 2 SD improvement on self-esteem or well-being between baseline and measurements afterwards),

- participants with slightly increasing scores (less then 2 SD improvement on self-esteem or well-being),

- participants with slightly decreasing scores.

For these calculations, the highest SD (for the particular participant) was taken into account. It was checked whether the participants with slightly decreasing scores differed in any of the pre-measured characteristics; this proved not to be the case.

We also performed a visual inspection to examine whether the psychoeducation that four participants received during the pre-measurements had an effect on self-esteem and well-being. The conclusion was that psychoeducation had no clear effect on self-esteem or well-being. Table 2 [Tab. 2] shows which participants improved and which participants deteriorated. The results of the multilevel analyses, at group level, are detailed in Table 3 [Tab. 3].

Table 2: Results of all participants grouped together

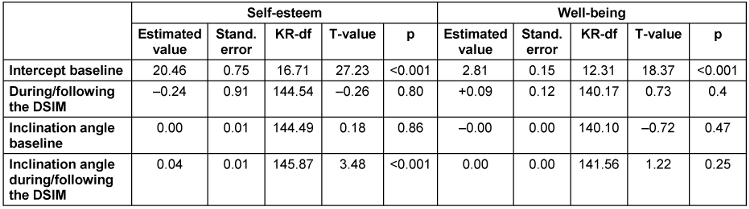

Table 3: Multilevel analysis of all eleven participants, considering condition and time

Table 3 [Tab. 3] shows that group-level RSES and MHC-SF scores do not significantly increase or decrease during the pre-measurements, while RSES scores do increase significantly during and following the module. MHC-SF scores do not increase significantly during or following the DSIM.

This analysis was repeated with the eight participants who took part in the entire module. The results of this analysis show that among participants who took part in the entire module, group-level scores on both the RSES and the MHC-SF increased significantly during and following the module. Assuming that improvement might be non-linear, we also looked at a quadratic relationship among the first eight participants; this did not yield significant improvement.

In summary, we can say that hypothesis 1 was confirmed by the analyses. Hypothesis 2 was also confirmed for participants who took part in the entire module. Participation in the DSIM is thus related to an increase in self-esteem, even if only part of the module is attended. Participation in the entire module is additionally related to an increase in well-being.

Answering the questions: qualitative

In the Change Interviews [53], participants (n=8) were generally positive about the module. Some of the feedback received included good structure, pleasant group and confrontational (stirred up a lot of things). The group size (three to five participants) was considered agreeable. In addition, it was striking that nearly all respondents felt that the module was too short, for most of them both in duration per session and in number of sessions.

The participants listed a multitude of changes they experienced in the course of the module. Many changes mentioned were related to self-esteem. For example, one change that was frequently mentioned is that they became aware of their negative self-image, their ‘inner critic’ and its roots in their past. Client 9: “That sometimes made me a bit angry. (...) To start realising what you are doing to yourself”. They had generally come to believe a little more that they were good enough, realising “...that I matter too!” (client 6). These changes were generally rated as being very important for the participant. In addition, participants mentioned more general changes, such as becoming more open. Furthermore, many respondents also mentioned that they were able to release and/or express emotions. Such changes were often not expected in advance but were experienced as important. When asked what had not changed, many participants indicated that they were still unable to look in the mirror with real satisfaction.

Asked to which factors they attributed the achieved changes, both external factors and components of the module were mentioned. Several exercises were mentioned, such as the „catwalk“, a recurring exercise, in which participants individually walk on a kind of catwalk, showing first their negative self-image and later a more positive self-image: “... to be in the spotlight like that. I don’t like that at all. (...) You do cross some kind of threshold” (client 1). Homework assignments were also felt to be helpful. Two of the participants engaged in rescripting. This exercise was experienced by a participant (client 4) as “...very emotional”.

When asked what was helpful in the module, the answers varied somewhat. Some called all assignments helpful; others benefited a lot from one assignment and little from another. More than once, role-playing was called helpful: “the role-play in which I stood up for myself. And yes, that did feel very unnatural to me ... So that did help me a lot to gain insight in what am I doing (...)” (client 8). The emotional experience was also mentioned in this context: “It’s a confrontation of sorts... yes, just by doing it, you know. Yes, it’s really the experience of engaging” (client 3). “... I have thought a hundred times about ways in which my mother should have reacted differently. (...) And then acting them out, that does make it real” (client 4). Homework was considered helpful by some. Several participants indicated that doing an assignment they were dreading actually helped them: “... for me (...) it confirms that I can do it after all” (client 3). Apart from the catwalk exercise and role-plays already mentioned, the exchange of experiences, writing down the aspects of their negative and positive self-image, making flashcards (a homework assignment) and the assignment to give yourself something nice were also mentioned. The therapist was viewed as positive, too: warm, light-hearted and serious.

As an unhelpful aspect of the module, lack of time was mostly mentioned. Due to the lack of time, not everyone was given an equal amount of time in sessions and sometimes things were cut short. Some participants also experienced insufficient opportunity to reflect on their feelings, or on how to do things differently, due to lack of time. Time pressure also limited perceived safety for one respondent. “It makes me feel less safe (...) If I find something very difficult, I just need more time and space to take that step of... that step to engage” (client 3). In the same vein, one negative aspect mentioned was that emotions were stirred up, but not always properly put to rest. One respondent felt the focus was too much on negative core thoughts and not enough on positive ones. On the other hand, another respondent would have preferred more emphasis on the causes of behaviour. The assignments that were experienced as most confronting were usually called difficult, but helpful.

Participants unanimously cited perseverance and discipline as the personal traits that helped them benefit most from the module. Almost all of them named these traits as a personal resource. Also mentioned was the strong intention to change things. Personal traits that hindered participants varied widely and included stubbornness, shame and wanting results right away. Asked about environmental factors that helped them to change, family and/or friends were mostly mentioned, as well as stopping or starting a job or education. Non-helpful environmental factors that were mentioned included strain from caring for family members, from work or school, and having to travel to therapy.

In summary, all participants experienced the module as mostly positive, although they perceived the module as too short. All participants could name at least one change that was important to them that they associated with taking part in the module. Most participants could name several changes, some related to improvement in self-esteem, some unrelated. Participants attributed the changes to different aspects of the module.

Discussion

This study examined the effect of the DSIM on clients with a personality disorder. Quantitatively, the effect of the DSIM on self-esteem and well-being was examined. In addition, interviews were used to inquire following the participants’ experience of the module and any changes they noticed in themselves.

The two hypotheses –that the DSIM leads to an increase in self-esteem and well-being- were confirmed: ten out of eleven participants increased slightly to strongly in self-esteem, nine out of eleven participants increased in well-being. This is in line with previous research into the DSIM by Hilderink [36]. The effect on self-esteem is stronger than on well-being, which should not be a surprise as the module is specifically aimed at improving self-esteem. Participants who could, due to circumstances, only take part in four of the six module sessions showed a significant increase in self-esteem, but not in well-being. Perhaps the full intervention is needed to benefit from an increase in well-being as well. This fits with the prior assumption that well-being can increase in the wake of self-esteem.

The combination of quantitative and qualitative data helps to obtain more nuanced information. Where the quantitative analysis of individual data suggest that the results are rather modest for most participants, the data from the interviews show that this modest change can be quite important for the individual. Participants seem to have become aware that low self-esteem is a matter of thought in their own heads, often learned by negative experiences in childhood. This makes the low self-esteem become ego-dystonic, which opens the way to further change. Furthermore, some participants mentioned unexpected but important changes that go beyond self-esteem and that were not visible in the quantitative data, such as becoming more open, or experiencing more contact with their emotions. This deserves further investigation.

The participants expressed positive perspectives on the module in the interviews, and they were all able to name at least one positive change that was very important to them, which they attributed to participation in the module.

If we compare the results of the interviews with the assumptions of drama therapy theory, the idea of direct physical and emotional experience is confirmed. The presence of an audience is an important factor as well. Role-playing is also mentioned in the interviews.

Does this mean that we can conclude that the DSIM works for this target group? The question is to what extent the results are due to the module itself, and to what extent they are related to the effect of participating in a study, so being given attention or being observed, the so called Hawthorne effect [57]. In this study, we sought to overcome this effect by including psychoeducation on schema focused therapy in participants’ pre-measurements. Our aim was to do this with all participants, but this turned out to be practically impossible. Therefore, we were only able to do this with four participants. Through psychoeducation, these participants received attention, but they were not subject to an intervention specifically aimed at improving self-esteem. We assumed that if attention in itself would lead to increased self-esteem and well-being, this would become apparent during and following psychoeducation. Yet, this was not the case: during and immediately after psychoeducation, scores on self-esteem and well-being remained more or less the same or even decreased slightly. Therefore, although only a small number of participants (four) were given psychoeducation at the time of the pre-measurements, it appears that the results were not exclusively caused by the attention given to them. Some recent studies [58], [59] found that simply participating in scientific research led to a positive effect on participants’ self-esteem. In our study, we did not witness this effect at the time of the pre-measurements, leading us to believe that the effect during and following the module is not purely due to research participation.

One limitation of this study is that all data are based on self-report. When completing the questionnaires and during the interviews, social desirability may have played a role, which may limit the results. However, all participants dared to express criticism during the interviews, mostly spontaneously. This suggests that social desirability did not play a major role.

Another limitation is the fact that the interviews were analysed only by the first author, without any interrater-reliability check. This limits the reliability of the qualitative data.

The generalisability of this study is limited by several factors. Adopting a single case experimental design has both advantages and disadvantages. The design is closely tied to clinical practices [38] and provides richer information than a randomised controlled trial, because it measures changes over time, thus saying something about the process of change [60]. However, the limited number of participants is a disadvantage. There were large differences in measurements between different participants. It seems that the intervention is more or less effective for different clients. No clear pattern can be distinguished in the characteristics of study participants for whom the module works well and participants for whom it works less well. Follow-up research could shed more light on this aspect.

The representativity of the study is limited for three reasons. Participation was voluntary: we may have had a very motivated group of participants due to the self-selection process. Also, the participants all mentioned their perseverance as a helping factor. In addition, we chose to include only clients who were indicated for outpatient schema focused therapy. At De Boerhaven, this is a subgroup of clients who have relatively few social problems and who are to some extent well-able to regulate their emotions. Ten of the eleven participants were women. It would be worthwhile to investigate the effect of the module on clients with personality disorders who are indicated for other forms of therapy, and to include more men. Finally, the module was always led by the same drama therapist. Many participants commented positively about her. The question remains whether the same results would be achieved with a different drama therapist.

Thus, there is evidence that the DSIM increases the self-esteem and well-being of clients with a personality disorder. Based on the interviews, expanding the length of the sessions and the number of sessions of the module could be considered. On the one hand, this is a defensible idea, as a personality disorder by definition involves long-term patterns that are often not easy to change. On the other hand, self-esteem appears to have increased even among participants who could only attend four of the six sessions. Future research could shed more light on the optimal length and number of sessions.

Finally, the question remains how the combination of this module with schema focused therapy works out for clients and what they think of it afterwards. It may be useful to include the DSIM in the therapy programme as a standard intervention. This is another topic for follow-up research.

This study suggests that in most cases the DSIM leads to a slight to strong improvement in self-esteem and well-being in clients with a personality disorder. Participants were unanimously happy to have taken part in the module. In practice, this means that the module can be a valuable addition to existing psychotherapeutic options for this target group, including within an outpatient setting.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants in this study and Teida Visser, drama therapist, for their efforts. They also thank Peter Bange and Peter ten Klooster for their contributions to the statistical analyses.

References

[1] Hilderink K. Een nieuw perspectief voor het zelfbeeld. De Dramatherapeutische Zelfbeeldmodule. Tijdschrift voor Vaktherapie. 2015;11(3):29-35.[2] Orth U, Robins RW. The development of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological science. 2014;23(5):381-7. DOI: 10.1177/0963721414547

[3] Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013 Jan;139(1):213-40. DOI: 10.1037/a0028931

[4] Waite P, McManus F, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for low self-esteem: a preliminary randomized controlled trial in a primary care setting. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;43(4):1049-57. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.04.006

[5] Forrester RL, Slater H, Jomar K, Mitzman S, Taylor PJ. Self-esteem and non-suicidal self-injury in adulthood: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017 Oct;221:172-83. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.027

[6] Keane L, Loades M. Review: Low self-esteem and internalizing disorders in young people - a systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2017 Feb;22(1):4-15. DOI: 10.1111/camh.12204

[7] Korrelboom K. Zelfbeeld. In: ten Ham BVH, Hulsbergen M, Bohlmeijer E, editors. Transdiagnostische factoren. Amsterdam: Boom; 2014. p. 241-62.

[8] Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(6):1069-81. DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.1069

[9] Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does High Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles? Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2003 May;4(1):1-44. DOI: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431

[10] Zeigler-Hill V. The connections between self-esteem and psychopathology. J Contemp Psychother. 2011;41(3):157-64. DOI: 10.1007/s10879-010-9167-8

[11] GGZ standaarden. Over persoonlijkheidsstoornissen. [Last updated: 2017]. Available from: https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/zorgstandaarden/persoonlijkheidsstoornissen-zorgstandaard-2017/over-persoonlijkheidsstoornissen

[12] American Psychiatric Association. Handboek voor de classificatie van psychische stoornissen: DSM-5. Amsterdam: Boom; 2014.

[13] Berghuis H, Ingenhoven TJM. Het alternatief DSM-5-model voor persoonlijkheidsstoornissen. PsyXpert. 2015;1:12-8.

[14] Ingenhoven TJM, Berghuis JG, Colijn S, Van HL. Handboek persoonlijkheidsstoornissen. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom; 2018.

[15] Rüsch N, Lieb K, Göttler I, Hermann C, Schramm E, Richter H, Jacob GA, Corrigan PW, Bohus M. Shame and implicit self-concept in women with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Mar;164(3):500-8. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.500

[16] Lynum LI, Wilberg T, Karterud S. Self-esteem in patients with borderline and avoidant personality disorders. Scand J Psychol. 2008 Oct;49(5):469-77. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2008.00655.x

[17] Santangelo PS, Reinhard I, Koudela-Hamila S, Bohus M, Holtmann J, Eid M, Ebner-Priemer UW. The temporal interplay of self-esteem instability and affective instability in borderline personality disorder patients' everyday lives. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017 Nov;126(8):1057-65. DOI: 10.1037/abn0000288

[18] Korrelboom K, Marissen M, van Assendelft T. Competitive Memory Training (COMET) for low self-esteem in patients with personality disorders: a randomized effectiveness study. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2011 Jan;39(1):1-19. DOI: 10.1017/S1352465810000469

[19] Korrelboom K. Versterking van het zelfbeeld bij patiënten met persoonlijkheidspathologie- ‘hot cognitions’ versus ‘cold cognitions’. DITH . 2000;20(3):134-43. DOI: 10.1007/bf03060241

[20] Roepke S, Schröder-Abé M, Schütz A, Jacob G, Dams A, Vater A, Rüter A, Merkl A, Heuser I, Lammers CH. Dialectic behavioural therapy has an impact on self-concept clarity and facets of self-esteem in women with borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(2):148-58. DOI: 10.1002/cpp.684

[21] Katsakou C, Marougka S, Barnicot K, Savill M, White H, Lockwood K, Priebe S. Recovery in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): a qualitative study of service users' perspectives. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36517. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036517

[22] Fennell MJV. Low Self-Esteem: A Cognitive Perspective. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1997;25(1):1-26. DOI: 10.1017/S1352465800015368

[23] GGZ standaarden. Vaktherapie. [last updated 2017, cited 2022 Mar 6]. Available from: https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/generieke-modules/vaktherapie/introductie

[24] van Hooren SAH, van Busschbach J, Waterink W, Abbing A. Werkingsmechanismen van vaktherapie: Naar een onderbouwing en verklaring van effecten-work in progress. Tijdschrift voor Vaktherapie. 2021;17(2):4-12.

[25] Koch SC. Arts and health: Active factors and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2017;54:85-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.02.002

[26] Orkibi H, Bar N, Eliakim I. The effect of drama-based group therapy on aspects of mental illness stigma. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2014;41(5):458-66. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2014.08.006

[27] Notermans H. Ontmoeten in spel. Heerlen: KenVaK Publishers; 2012.

[28] Noice T, Noice H. The expertise of professional actors: A review of recent research. High Ability Studies. 2002;13(1):7-19. DOI: 10.1080/13598130220132271

[29] Noice H, Noice T, Staines G. A short-term intervention to enhance cognitive and affective functioning in older adults. J Aging Health. 2004;16(4):562-85. DOI: 10.1177/0898264304265819

[30] Dunphy K, Mullane S, Jacobsson M. The effectiveness of expressive arts therapies: A review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal. 2014;2(1). DOI: 10.59158/001c.71004

[31] Armstrong CR, Frydman JS, Rowe C. A snapshot of empirical drama therapy research: conducting a general review of the literature. GMS J Art Ther. 2019;1:Doc02. DOI: 10.3205/jat000002

[32] Feniger-Schaal R, Orkibi H. Integrative systematic review of drama therapy intervention research. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts. 2020;14(1):68-80. DOI: 10.1037/aca0000257

[33] de Witte M, Orkibi H, Zarate R, Karkou V, Sajnani N, Malhotra B, Ho RTH, Kaimal G, Baker FA, Koch SC. From Therapeutic Factors to Mechanisms of Change in the Creative Arts Therapies: A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:678397. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397

[34] Keulen-de Vos M, van den Broek EP, Bernstein DP, Vallentin R, Arntz, A. Evoking emotional states in personality disordered offenders: An experimental pilot study of experiential drama therapy techniques. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2017;53:80–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.01.003

[35] Doomen L. The effectiveness of schema focused drama therapy for cluster C personality disorders: An exploratory study. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2018;61:66-76. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.12.002

[36] Hilderink K. De dramatherapeutische zelfbeeldmodule. Effectonderzoek naar het zelfbeeld bij cliënten met een angststoornis. Tijdschrift voor vaktherapie. 2015;11(4):55-9.

[37] Morgan DL, Morgan RK. Single-case research methods for the behavioral and health sciences. London: Sage publications; 2008. DOI: 10.4135/9781483329697

[38] Borckardt JJ, Nash MR, Murphy MD, Moore M, Shaw D, O'Neil P. Clinical practice as natural laboratory for psychotherapy research: a guide to case-based time-series analysis. Am Psychol. 2008;63(2):77-95. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.77

[39] Hurtado-Parrado C, López-López W. Single-Case Research Methods: History and Suitability for a Psychological Science in Need of Alternatives. Integr Psychol Behav Sci. 2015 Sep;49(3):323-49. DOI: 10.1007/s12124-014-9290-2

[40] Kratochwill TR, Levin JR. Enhancing the scientific credibility of single-case intervention research: randomization to the rescue. Psychol Methods. 2010 Jun;15(2):124-44. DOI: 10.1037/a0017736

[41] Keyes CL, Wissing M, Potgieter JP, Temane M, Kruger A, van Rooy S. Evaluation of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF) in setswana-speaking South Africans. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008;15(3):181-92. DOI: 10.1002/cpp.572

[42] Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1986.

[43] Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005 Oct;89(4):623-42. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623

[44] Huprich SK, Lengu K, Evich C. Interpersonal Problems and Their Relationship to Depression, Self-Esteem, and Malignant Self-Regard. J Pers Disord. 2016 Dec;30(6):742-61. DOI: 10.1521/pedi_2015_29_227

[45] Franck E, De Raedt R, Barbez C, Rosseel Y. Psychometric properties of the Dutch Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Psychologica Belgica. 2008;48(1):25-35. DOI: 10.5334/pb-48-1-25

[46] Everaert J, Koster E, Schacht R, De Raedt R. Evaluatie van de psychometrische eigenschappen van de Rosenberg zelfwaardeschaal in een poliklinisch psychiatrische populatie. Gedragstherapie. 2010;43(4):307-17.

[47] Lamers SM, Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET, ten Klooster PM, Keyes CL. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). J Clin Psychol. 2011 Jan;67(1):99-110. DOI: 10.1002/jclp.20741

[48] van Erp Taalman Kip RM, Hutschemaekers GJM. Health, well-being, and psychopathology in a clinical population: Structure and discriminant validity of Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF). J Clin Psychol. 2018 Oct;74(10):1719-29. DOI: 10.1002/jclp.22621

[49] De Beurs E, Zitman F. De Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): De betrouwbaarheid en validiteit van een handzaam alternatief voor de SCL-90. Leiden: Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum; 2013.

[50] Verheul R, Andrea H, Berghout CC, Dolan C, Busschbach JJ, van der Kroft PJ, Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Severity Indices of Personality Problems (SIPP-118): development, factor structure, reliability, and validity. Psychol Assess. 2008 Mar;20(1):23-34. DOI: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.1.23

[51] Elliott R, Slatick E, Urman M. Qualitative Change Process Research on Psychotherapy: Alternative Strategies. Psychologische Beitrage. 2001;43(3):69–111.

[52] Elliott R. Qualitative methods for studying psychotherapy change processes. In: Harper D, Thompson AR, editors. Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. p. 69-81. DOI: 10.1002/9781119973249.ch6

[53] Rogers B. Change Interview. [last updated 2011, cited 2022 Mar 6]. Available from: http://www.drbrianrodgers.com/research/client-change-interview

[54] Ledford JR, Lane JD, Severini KE. Systematic use of visual analysis for assessing outcomes in single case design studies. Brain Impairment. 2018;19(1):4-17. DOI: 10. 1017/Brlmp.2017.16

[55] Moeyaert M, Ferron JM, Beretvas SN, Van den Noortgate W. From a single-level analysis to a multilevel analysis of single-case experimental designs. J Sch Psychol. 2014 Apr;52(2):191-211. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsp.2013.11.003

[56] Declercq L, Cools W, Beretvas SN, Moeyaert M, Ferron JM, Van den Noortgate W. MultiSCED: A tool for (meta-)analyzing single-case experimental data with multilevel modeling. Behav Res Methods. 2020 Feb;52(1):177-192. DOI: 10.3758/s13428-019-01216-2

[57] Plochg T, Juttmann RE, Klazinga NS, Mackenbach JP. Handboek gezondheidszorgonderzoek. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2007. p. 124.

[58] Gunn JK, Roth AM, Center KE, Wiehe SE. The Unanticipated Benefits of Behavioral Assessments and Interviews on Anxiety, Self-Esteem and Depression Among Women Engaging in Transactional Sex. Community Ment Health J. 2016 Nov;52(8):1064-9. DOI: 10.1007/s10597-015-9844-x

[59] Tross S, Pinho V, Lima JE, Ghiroli M, Elkington KS, Strauss DH, Wainberg ML. Participation in HIV Behavioral Research: Unanticipated Benefits and Burdens. AIDS Behav. 2018 Jul;22(7):2258-66. DOI: 10.1007/s10461-018-2114-5

[60] Hadert A, Quinn F. The individual in research: experimental single-case studies. Health Psychology Update. 2008;17(1):20-6. DOI: 10.53841/bpshpu.2008.17.1.20

[61] van den Broek E, Keulen-de Vos M, Bernstein DP. Arts therapies and Schema Focused therapy: A pilot study. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2011;38(5):325–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2011.09.005