[Orientierungsmuster von Hebammen bei der Geburt in verschiedenen Gebärräumen – eine rekonstruktive Studie]

Karolina Luegmair 1Gertrud M. Ayerle 1

Anke Steckelberg 1

1 Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Geburtshilfe in Deutschland zeichnet sich aktuell durch einen hohen Anteil an Kaiserschnitten aus. Bestrebungen, diese Rate im Sinne von WHO-Empfehlungen deutlich zu senken und mehr Frauen vaginale Geburten zu ermöglichen, beziehen auch eine veränderte räumliche Gestaltung klinischer Gebärräume ein.

Ziel: Untersuchung der Handlungspraxis im Sinne von handlungsleitenden Orientierungen von Hebammen bei der Arbeit im alternativ gestalteten Gebärraum und Kontrastierung mit handlungsleitenden Orientierungen von Hebammen bei der Arbeit im üblich gestalteten Gebärraum.

Methodik: Qualitativer Ansatz mit insgesamt 16 narrativ-orientierten themenzentrierten Einzelinterviews mit Hebammen aus unterschiedlich gestalteten Gebärräumen und Auswertung dieser mit der Dokumentarischen Methode.

Ergebnisse: Orientierungsmuster tragen zur Erklärung der Handlungspraxis von Hebammen in unterschiedlichen Gebärräumen bei, wenn man Aspekte der grundlegenden Betreuungsmöglichkeiten, professionsbezogenen Sozialisierung und Haltung zum Raum betrachtet. Eine Orientierung an Gebärenden kann dabei nicht konstant vollzogen werden, wenn Probleme auf relevanten Dimensionen erlebt werden.

Diskussion und Schlussfolgerung: Die Handlungspraxis von Hebammen kann nicht losgelöst von der Gestaltung des Raumes erklärt und verstanden werden. Erst wenn alle Dimensionen der Handlungspraxis von Hebammen betrachtet und notwendige Veränderungen angestoßen werden kann Hebammenarbeit im Sinne einer durchgängigen Orientierung an Gebärenden realisiert werden.

Schlüsselwörter

Kreißsaal, Design, Hebamme, Praxis, Orientierung

Background

In Germany, more than 98% of births take place in a hospital setting [10] and the mode of delivery in nearly one-third of births is Caesarean section, which is relatively high compared to other European countries [20]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation is that C-sections should be performed as a lifesaving intervention but not as a routine measure. Instead, attempts should be made to enable all women to have a self-determined and safe birth [30]. In Germany, hospital births are usually accompanied by a team of medical staff and midwives, with physician-led obstetrics the most common form. Midwives must, however, at least be consulted in the birth [11]. Moreover, in day-to-day clinical practice, midwife care throughout the entire birth process is the primary model. This care is made more difficult by the external conditions, which are marked by understaffing, increasingly strict requirements and generally more challenging working conditions. Some of the reasons for these difficulties are the concentration of births in a smaller number of hospitals offering midwifery care, an accumulation of overtime and an increase in staff carrying out tasks that they are not trained in [1]. When it comes to out-of-hospital midwifery care, on the other hand, despite the fluctuations over the last few years, these still account for less than 2% of all births in Germany [10]. Out-of-hospital midwifery takes place under a wide range of different conditions: to be supervised exclusively by a midwife, a pregnant woman must be categorised as low risk, and, for every birth, the premises and equipment must be checked for their suitability by the home birth assistance team and be set up for the purposes of childbirth. Moreover, the attending midwife herself has a different type of responsibility; team work is not the most important thing here, despite the fact that this is embedded in the system [24]. The conditions in hospital and out-of-hospital midwifery thus differ considerably. The working practice of midwives should not, however, be interpreted without taking the conditions of the material environment into consideration, and this includes the layout of the birthing room and general external conditions. This enables us to overcome a confirmed “technological or spatial blind spot”, something which has so far been defined as the attempt to understand human action without considering non-human actors [22]. By also considering the non-human elements of an action, we may even gain a better understanding of the midwives’ working practice in space [8]. The actors in the context of a hospital birth include both the woman in labour and their birth partner/s along with the medical staff supervising the birth.

In connection with efforts to improve hospital midwifery, the aim of enabling women to have self-determined births with less intervention has featured in considerations on the architectural redesign of hospital birthing rooms for years [6], [12]. The reasons for this are derived from findings on the complex interconnectedness of spatial and technical conditions and human action. It is assumed that both the design of the space and the perception of objects (technical actors) in that space drive their routine use [13]. This perception facilitates normative regulation and also gives rise to emotions among the actors (human actors) [11].

To address the lack of research on different designs of hospital birthing rooms, in 2018, “Be-Up: Geburt aktiv”, a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT), was initiated [3]. The aim of the study was to investigate whether a redesigned birthing room which seeks to remove the delivery bed as a central feature and foster maternal mobility has an impact on the rate of vaginal births (VB) [4]. Here, too, the background to setting this objective involved considerations regarding the interaction between the design and layout of the physical space and the person acting in that space. The findings show that the number of vaginal births in the intervention birthing room increased – yet, so too did the number in the study control group. It was thus not possible to identify clear effects of the alternative birthing room. Rather, context-related conditions (such as the possibility of randomisation with simultaneous availability of two birthing rooms and thus an indicator of a delivery room that was not fully occupied) appear to have played a role [3]. In the context of the “Be-Up” study, the present study on midwives’ orientations in conventional and alternative birthing rooms was developed in order to better understand the working practice of midwives in the differently designed birthing rooms.

In preparation for the present study, we conducted a synopsis of international research work in which the general action-guiding orientations of hospital midwives are examined [15] and a qualitative reconstructive analysis of midwives’ action-guiding orientations in conventional hospital birthing rooms in Germany [16]. Capturing the action-guiding orientations enabled us to reconstruct a form of knowledge which determines the working practice and becomes visible through the relationship between norms, patterns and the working practice exhibited [8]. In the aforementioned study, a basic typology was developed which depicted midwives’ practical knowledge as being situated in an area of tension between aspiration and implementation. The three reconstructed types “midwifery practice in balance with aspiration and implementation”, “midwifery practice torn between aspiration and implementation” and “in the unresolved dilemma between aspiration and implementation” are located on a continuum between the two poles of solution and lack of solution to a dilemma resulting from aspiration and implementation [16]. A midwife who has certain aspirations regarding her own professional practice and expects these standards to be met when assisting childbirth faces a dilemma insofar as her own aspirations cannot be consistently fulfilled (“torn between aspiration and implementation”). Thus her working practice deviates from her aspirations, resulting in a form of conflict. In contrast, midwifery is in an “unresolved” dilemma between aspiration and implementation if this gap between aspiration and implementation is fundamentally there but the deviation is no longer countered by attempts to solve the dilemma or if there has been a form of adaptation to the circumstances. With regard to the “in balance with aspirations and implementation” type, however, such discrepancies are never or only rarely present. If discrepancies do occur, these can be actively countered and the midwife experiences few difficulties in fulfilling her role in line with her own aspirations.

Aim

The aim of the current study was to conduct a qualitative reconstructive analysis of the possible influence of alternatively designed birthing rooms on the action-guiding orientations of the midwives working there, subsequently contrasted with the orientations of midwives working in conventional birthing rooms or assisting home births.

The following research question was examined:

Which action-guiding orientations do the midwives demonstrate in the alternative birthing room (“Be-Up” birthing room) from the “Be-Up: Geburt aktiv” study?

Method

The reporting below adheres to the COREQ guidelines [26].

Design

In order to capture individual action-guiding orientations in the conjunctive space of experience of midwifery, a qualitative reconstructive research approach with the survey method of narrative-oriented, topic-centred [29] individual interviews was chosen along with parallel data analysis. For the reconstruction of the working practice and action-guiding orientations, the documentary method was selected, which, thanks to its ability to access to the implicit knowledge that is responsible for the smooth implementation of complex actions, has also proven to be useful in the midwifery profession [16]. Here, methodically controlled norms and patterns are reconstructed from argumentative passages and related to habitual action from narrative passages. This enabled us to reconstruct action-guiding orientations and possible discrepancies, thus facilitating access to working practice [7].

The main author conducted the interviews. She is a midwife herself and was transparent about her shared professional background when explaining the interview process to the interviewees. In order to enhance access to the conjunctive space of experience, it is helpful if individuals are able to understand one another without having to rely on in-depth explanations at the communicative level [16], can draw on common experiences, reduce argumentative explanations and structure their narration with no need for explanation.

Sampling

In order to capture midwives’ action-guiding orientations when assisting births in an alternatively designed birthing room, a strategy was drafted to draw a convenience sample of midwives with direct experience of working with the “Be-Up” birthing room. Access to the hospitals involved in the “Be-Up: Geburt aktiv” study was facilitated by the second author and participants for the current study were sought via letter and through personal contacts. A meeting was then arranged with potential participants outside working hours. For contrast, we also sought midwives with experience in assisting home births. In addition to this, midwives working outside the hospital setting were approached directly and via a nationwide email list for out-of-hospital midwives. Midwives from both settings who responded to the calls for participants were either invited by email or in some cases in person to take part in the study. The action-guided orientations of midwives working in the conventional hospital setting were already captured in a previous study [16].

Interview setting and data collection

The interviews, which were digitally recorded, were conducted in private, either in person or virtually, depending on the pandemic-induced restrictions at the time. The key factor here was the participating midwife’s personal preference. The interviewer took hand-written notes, already anonymising the data and notes at this point, which were only stored under the participant’s alias. In preparation for the interview, the interviewees were presented with a detailed verbal and written explanation of the aim of the study along with a data protection declaration. Only once the participant had given verbal and written consent was the interview commenced.

The interview guide used was created by the authors, drawing on relevant literature on midwives’ working practice and room layout and was tested and adapted in a test interview. The function of the initial stimulus selected to prompt the interviewee to describe the most recent birth they assisted can, on the one hand, be seen as an indicator of them being assigned to a hospital or out-of-hospital space of experience [11]. On the other hand, the statements made by the interviewees enable us to capture and reconstruct setting-specific knowledge. The initial stimulus was (with minor variations): “The aim of my study is to understand how midwives behave when assisting a hospital birth in the ‘Be-Up’ birthing room/when assisting a home birth. What is it like for you to work as a midwife in that setting? Perhaps it would help if you told me about the last birth you assisted.” This initial stimulus was followed by thematic blocks on working practice during births, the design of the room and on wishes and ideas for the midwifery profession.

Documentary method and analysis

We followed a strict data anonymisation and masking approach from the start of the project; the recordings and transcripts were all password protected and were stored without the use of real names. Original files were destroyed immediately after the end of the project.

In order to properly address the research question regarding the situation in the changed spatial environment, we integrated and applied the view on the technical conditions in the room and the reconstruction of a possible “contagion” [8], [23]. The aim here was to take into account the technical weight of changed external conditions [23]. Aspects are integrated from sociotechnology or the actor–network theory (ANT), in which the joint actions of humans and technology are examined [5], [8]. In this way, the interpretation is also given a theoretical framework tailored to the research subject. Beyond the praxeological sociology of knowledge on which the documentary method is based, this framework offers explanatory approaches to action in the context of spatial conditions. This means that we can capture the process structures of behaviour with regard to the design of the birthing room if the constituent conditions are considered in their entirety – only in this way can we identify the genesis and execution of actions based on motives and thus reconstruct their correlation with behaviour [19].

In order to understand this connection between the basic assumptions of the ANT and the documentary method, it is important to take different forms of intentionality into consideration. Here, human actors are attributed an implicit intentionality, which can be retrospectively justified argumentatively but must nevertheless be considered in the context of the actual action. Technical and other agents (in other words, actors), in contrast, are attributed an explicit intentionality, which is in line with the purpose and is thus apparently immediately understandable. The combination of human and technical actors to form a hybrid actor creates a mixed implicit-explicit intentionality [28]. In the context of interpretation and reconstruction, the steps of the documentary method can thus be used to understand the intentionality of the actions of human actors and relate them to the design of the space.

The full text of the interviews was transcribed and then subject to the analysis and interpretation steps of the documentary method. For the introductory and concluding parts of the text, for those who talk about the room, and for those with high narrative and/or performative density, we applied a formulating and reflecting interpretation with semantic analysis. At the same time, from the very start of the study, we carried out a comparison between the individual cases of the “Be-Up” room and the home birth midwives as well as with the interviews from the conventional birthing room. We did this in order to identify the homologies but also the differences between the individual cases and to verify the types established in the preliminary study [18]. In this process of constant comparison, orientation patterns were sought which guided midwives’ practice in the conventional and the alternative (“Be-Up” or home birth) birthing room. Here, the function of the individual agents (technical and human) was rigorously examined in terms of the ANT, in order to compare possible working practices of the interviewees with the existing norms and patterns. Here the respective spatial and general framing (hospital/out-of-hospital) of the midwifery assistance was always taken into account as well, with the aim of factoring the different conditions into the interpretation. In order to conduct the afore-mentioned steps from transcription to analysis and reconstruction, MAXQDA software was used in a procedure adapted to the documentary method [27]. To ensure the quality of the analysis and reflect on the impact of the local and social belonging of the interviewer (Standortgebundenheit), the processes intrinsic to the documentary method were consistently followed and the interpretations were discussed at several research workshops. Constant self-reflection also took place to take the conjunctive space of experience into consideration from a more detached position. This was achieved by discussing the results explicitly with experts from outside the field who were nevertheless familiar with the scientific approach of the documentary method [8].

Seven midwives participated, four from hospitals that took part in the “Be-Up: Geburt aktiv” study and three from the home birth assistance setting. Two other potential candidates from hospitals in the “Be-Up” study did not participate after the initial contact for personal reasons.

The survey was conducted by the main author in the period from July 2021 to March 2022; the interviews lasted an average of 86 minutes each (ranging from 52 to 157 minutes). The occupational background along with other background details about the participants are displayed in Table 1 [Tab. 1]. The names used here are aliases.

Table 1: Key information on occupational background for whole sample

Results

One case could not be assigned to any of the types created, as only part of the interview could be analysed due to technical problems. However, some of the approaches to the initial interpretation of this interview were included in the further development of the dimensions.

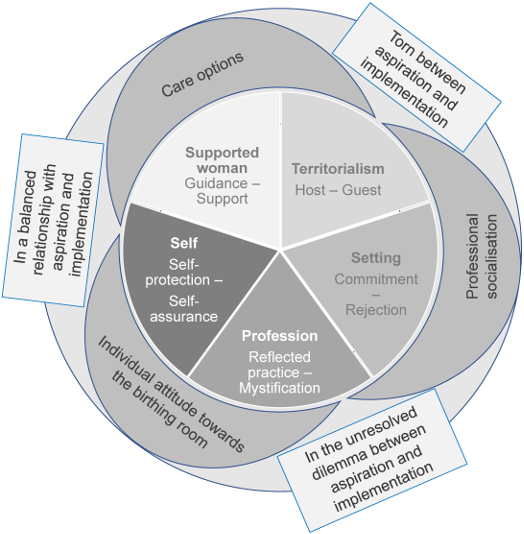

The five dimensions of midwives’ working practice

In the four dimensions already reconstructed in a previous study conducted by the authors [16], there was evidence of relevant homologies and differences when it came to midwives’ working practice. With regard to the dimension of the “supported woman”, midwives’ working practice was shown on a continuum between support and guidance. When it came to the “hospital setting” dimension, the midwife’s commitment to or rejection of the setting could always be reconstructed. In relation to “the self”, facets of self-protection and self-assurance could be reconstructed. The working practice for the “midwifery profession” dimension is expressed in the domain of reflected practice and mystification of the profession [16].

The “sovereignty over the space” dimension reconstructed in the present study was also experienced along a spectrum between two poles by the midwives interviewed. It is thus determined that the midwife either behaves like a guest in the room or assumes the hostess role. In the guest role, the midwife respects the privacy and authority of the birthing mother, physically withdraws to the edge of the room and is also restrained in her actions.

This role is assumed by the midwife in the home birth setting but cannot be performed in a hospital setting. Here it is revealed that, under certain circumstances, the “Be-Up” birthing room significantly facilitates the birthing mothers’ sovereignty to act.

These enabling circumstances include the possibility of providing the woman with close supervision (e.g. one-to-one). However, we also identify a shift of the sovereignty over the space and the processes in it towards the birthing mother in the conventionally designed birthing room. That being said, in the case of the conventional room design, the midwife has to make adjustments to the layout of the room, which means the authority remains in her hands; a complete shift of authority to the labouring woman is only possible in exceptional cases. The situation seems to be different in the “Be-Up” birthing room; the midwife makes no or very few changes to the layout of the room and the labouring woman may be able to move and act more freely. Thus the “Be-Up” room is a resource contributing to the autonomy of the birthing woman when it comes to her midwife care. That said, this autonomy can be experienced as an obstacle if the layout of the room and working conditions in which the care is provided are not optimally combined. For instance, on the one hand, in the event of an emergency, the room layout deviating from the conventional design is found to present both a spatial and mental obstacle for the midwife and the labouring woman loses her authority. On the other hand, the birthing woman can also lose her authority if organisational conditions make the midwife’s work more difficult.

When the midwife plays the role of the “host” in the room, she strongly guides the birthing woman’s actions and how she uses the room, often also to minimise the risk to the birthing woman. This makes the link to the four dimensions reconstructed above – “supported woman”, “hospital setting”, “the self” and “midwifery profession” – clear. In connection with the respective prevailing conditions, the labouring woman experiences these dimensions as tailored care, which is at the centre of midwifery practice.

Integration into an existing basic typology

We found that our assignment to the three types within the basic typology “the midwife situated between in the area of tension between aspiration and implementation” [16] was, after critical consideration, consistent in all cases. Thus, on the one hand, the area of tension reconstructed above were supported and, on the other, it could also be deduced that the design of the room did not cause any direct change in the underlying action-guiding orientations.

Three orientation patterns in midwifery practice in different types of birthing rooms

The interconnectedness and complexity of all dimensions is clearly shown by the moderating function of the orientation patterns that result from the reconstruction of midwifery practice in different settings ([14], p. 40), (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). These orientation patterns differ, particularly in terms of the feasibility of aspirations, initially independent of the design of the room. They relate to 1) basic care options, 2) the professional socialisation of the midwife and 3) her attitude towards the room. In the interplay of individual orientations, a pattern is revealed that explains the feasibility of individuals implementing their own professional aspirations in their midwifery practice.

Figure 1: Orientation patterns in midwifery practice

Basic care options

If the midwife is able to meet her own expectations and shape the care she provides to birthing mothers in the way she personally intends, then the care options correspond to the midwife’s vision. In most cases, this vision involves one-to-one supervision of the woman or at least one-to-two, which, in a hospital setting, is only possible in exceptional cases.

More often than not, however, this form of care cannot be provided due to the high workload and thus often remains wishful thinking.

That said, the actual care options and the midwives’ normative expectations sometimes contradict each other in the other direction. Thus, midwives who are most frequently assigned to the “in the unresolved dilemma of aspiration and implementation” type no longer explicitly wish to provide close support for labouring women. Rather, these midwives actively try to accept the existing conditions to maintain their ability to act.

The alternatively designed room underlines the fundamental potential to fulfil the midwife’s aspirations but also the difficulties that arise if this does not happen. Thus the support and care provided to the labouring mother can depend on the general conditions even in the alternatively designed room. The design of the room alone does not automatically lead to the strengthening of the woman’s autonomy. Rather, clinical guidelines restrict the autonomy of the birthing mother to move during labour, even in the eyes of the midwife. As a result, the midwife has to deviate from her aspirations when providing care (in order to meet the requirements) and ultimately provides a form of care that makes it difficult for the birthing woman to remain active during labour.

Professional socialisation

When they are assisting a birth, midwives show different forms of professional socialisation. However, these differences cannot exclusively be put down to the respective setting. Rather, the possibility of fulfilling individual aspirations seems to be in evidence here as well. Thus, in their orientation towards the birthing woman, the midwives demonstrate a high level of satisfaction and an ability to act if the realities of midwifery work correspond to their own ideas of gearing their actions towards a physiologic birth. However, both in the hospital and out-of-hospital setting, the perception of whether or not these ideas are fulfilled properly varies from individual to individual.

With midwives who are “torn between aspiration and implementation”, one thing that became clear was that the demands on midwifery and the realities strongly influenced the perceptions of what was experienced. If the circumstances deviated significantly from the aspirations, a form of the aforementioned dilemma became clear, especially when it seemed impossible for the midwife to change the situation through her own actions.

In addition, there is a correlation with the potential the midwife believes she has to change the situation in the event of an existing discrepancy between aspiration and implementation. The midwives assigned to the “torn between aspiration and implementation” type are still searching for this potential, while the “in balance” type believe they have successfully achieved it. The “unresolved dilemma” type, on the other hand, no longer even aspires to a solution for this discrepancy. This perceived potential is illustrated by the midwives’ professional decisions to remain in the respective setting or leave it.

If a midwife is assigned to the “torn between aspiration and implementation” type, her own affiliation to the respective setting is either not entirely decided or a form of irreconcilability with the other (out-of-hospital) setting is present. For midwives of the “unresolved dilemma” type, the respective alternative setting is not even an issue; it is simply not considered. Moreover, the midwives assigned to the “in balance” type make a conscious decision to remain in the current setting, while retaining an openness to the alternative hospital or out-of-hospital setting.

Attitude towards the room

The midwives surveyed all have a basic opinion on the respective birthing room and its design, which also coincides with their individual orientations, in particular, and corresponds to the basic status regarding the fulfilment of their aspirations. Thus the perception of the room is either helpful or a hindrance to the midwives in their professional practice. This perception is reflected in the differently designed rooms of the setting in conjunction with their perceptions of their own potential for action. Thus even a conventional birthing room is experienced as conducive for their own professional practice if midwifery work is perceived as appreciated in the respective setting. Conversely, obstructive elements are particularly strongly perceived when this recognition seems to be in short supply.

In the context of the alternatively designed room, it can be said that, here too, elements that are beneficial to or hinder the midwife’s work are very much in the foreground of professional practice. This leaves the difficulty of having to remove unfamiliar elements in the event of an emergency, despite the fact that the fundamental orientation towards supporting a normal physiologic birth process can be strongly promoted by these elements.

Discussion

Results

In this study, it was possible to reconstruct the midwives’ action-guiding orientations while attending births in the alternative birthing room. We found that the dimensions of midwives’ working practice, irrespective of the type of birthing room, fall into five areas. Moreover, we were able to reconstruct patterns of orientation which help explain the genesis of midwives’ working practice.

In using the documentary method, which serves to reconstruct the tensions between norm and habitus, the findings presented here add to the insights provided by comparable studies on the alternative design of birthing rooms. In these rooms, the midwives experienced the alternative design as providing them with explicit support in attending normal physiologic births [2]. The current study also substantiated this explicit support. Correlating this with the existing working conditions also resulted in a more fundamental supportive context, which showed a clear affiliation to the general conditions of the work setting. Looking at their professional attitude towards their own setting and its specific characteristics (physician-led obstetrics in the hospital setting, predominance of personal responsibility in the home birth setting) helps us to understand the midwives’ reactions to these specific characteristics in terms of their professional practice. Here it would be important for a midwife to reflect, in a focused manner, on their own practice in order to make sure that the significance of these reactions do not dominate, especially if they stem from the tensions between aspirations and implementation. This finding is also consistent with other studies from German-speaking countries, in which risk orientation was correlated with setting-related circumstances [21]. In the present study, it was possible to reconstruct indications of connections between the experience of the room layout and the midwife’s own working practice, which suggest a form of interconnectedness between design and practice that the midwives surveyed did not yet seem explicitly aware of. The tension between aspiration and implementation continues to guide midwives’ actions.

The study also showed that the elements of the alternative room and midwives’ perceptions of these elements confirm the fundamental action-guiding orientation pattern and needs and are thus not isolated from one another. Despite this, they are experienced as a strengthening factor in practice. Thus, changed practice resulting from the redesign could not be reconstructed. Rather the move towards a new room layout is to be seen in alignment with existing knowledge, whereas the attitude towards the room can be seen as fundamental. In the process, existing knowledge is transferred to the new situation and thus influences and changes the external conditions of the objects and interacts with them – albeit adapted to individuals’ own knowledge. In summary, this can be described as a process that corresponds to findings on the habitualisation of actionist behavioural patterns [9]. Whether or not the space is used as envisaged appears to depend on the individual’s existing knowledge and is difficult to predict or guide. Ideas for the flexibility of knowledge and how to deal with it also reveal generation-specific conditions, especially when it comes to dealing with technical artefacts; from this we can also derive potential feelings of unfamiliarity when encountering innovations [23].

That said, the study did demonstrate clear traces of a change in the midwives’ experience of their own potential to act in the alternatively designed birthing room. This changed experience can also be explained by what is known as a “contagion of things”: interactions between the agents are evident when both parties change through their experience as a hybrid actor [23]. More in-depth analyses of this change could help us gain an even better understanding of midwives’ behaviour in connection with the layout of the room, so as to raise awareness of and reflect on this topic as well as to integrate it into practice in the field of education and training.

Professional socialisation also requires further research in order to integrate the relationship between this and midwifery practice into the training of future and young midwives. In addition to interventions that have already been conducted, this reflection could contribute to an increased orientation towards physiology among midwives already during their first years of professional practice and could make a positive contribution to supporting labouring women even in a hospital setting [25].

In the context of the action-guiding orientation towards the individual care options, we can derive demands for an improvement in the conditions of midwifery care in the hospital setting, which were already identified in other studies [1]. For instance, it appears that it is only possible to ensure that midwifery work is sustainably oriented towards the wishes and needs of the birthing woman with a significantly and permanently improved midwife-to-mother ratio.

Strengths and weaknesses

With this study, we were able to reconstruct midwives’ orientation patterns in the alternatively designed birthing room with a view to drawing conclusions for midwifery work. Although participation of hospital midwives in the “Be-Up: Geburt aktiv” study was limited (just four midwives), the study provided a varied picture of hospital and out-of-hospital midwifery work under the conditions of the respective birthing room. Regarding the lack of willingness of midwives to participate in the study, we can assume that this was related to a high workload during the pandemic, as well as repeated requests to participate in this and other studies. This may have resulted in an overload effect due to the frequency of requests. Nevertheless, a form of content saturation could be determined, since the main features of action-guiding orientations and orientation patterns could already be reconstructed after the first four interviews. Contrasting with out-of-hospital midwives in our efforts to reconstruct the action-guided orientations in different types of birthing room made the desired reconstruction possible. The midwifery practice showed diverse inherent orientations, independent of the setting. The fact that the main author had the same professional background as the interviewees can be seen as a resource for a study of midwifery practice in the context of a conjunctive space of experience.

At the same time, this shared background could also be seen as a possible weakness of the study and had to be continuously reflected on with a view to addressing the local and social belonging of the interviewer. Another weakness that should be mentioned is that saturation of results can only be assumed to a limited extent, because recruitment in the hospitals that were part of the “Be-Up: Geburt aktiv” study proved to be so difficult. Despite intensive efforts and multiple calls for participation, it proved impossible to attract any more interviewees from the “Be-Up” room. Moreover, all the midwives surveyed expressed their support of the concept of the study and room – findings from midwives who rejected the study could certainly have contributed further aspects. A third possible weakness is the fact that some of the interviews had to be conducted virtually. Here, too, the conjunctive space of experience quickly contributed to a familiar situation (despite the spatial distance) and thus enabled the reconstruction using the documentary method. Since the interviewees reported being familiar with virtual conferences at the time of the interview and since they could also chose between the virtual or in-person interview themselves, no traceable hierarchy arose in favour of the interviewer in the interview [17].

Conclusion

It can be concluded that concerning midwives who assist births, fundamental normative and habitual orientations are also reflected in their attitude towards the birthing room. Here, individual midwifery practices can be observed in complex interaction with the spatial, organisational and staffing conditions, which make midwifery work more transparent and thus offer prospects for further development. This can be seen, in particular, in their attitude towards the room and their perception of its function – both in the conventional hospital and in the two alternative settings. Individual orientations predominate. If these are in a fundamentally unresolved dilemma or in conflict, the room can only make a limited innovative contribution. Rather, the space is integrated into the established behaviour and can only exert its effect in a situation-specific manner. If this fundamental tension is addressed, the midwives are made aware of it and structural improvements are facilitated to help counteract the tension, there is a chance that the change in the design of the room can also change the care of birthing women.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

While working on the study, the main author received an 18-month scholarship from the Landeskonferenz der Frauen- und Gleichstellungsbeauftragten an Bayerischen Hochschulen (LaKoF Bayern). This had no influence at any time on the design or implementation of the study.

References

[1] Albrecht M, Loos S, an der Heiden I, Temizdemir E, Ochmann R, Sander M, Bock H. Stationäre Hebammenversorgung: Gutachten für das Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Berlin: IGES Institut; 2019. Available from: https://www.iges.com/kunden/gesundheit/forschungsergebnisse/2020/hebammen/index_ger.html[2] Andrén A, Begley C, Dahlberg H, Berg M. The birthing room and its influence on the promotion of a normal physiological childbirth – a qualitative interview study with midwives in Sweden. Int J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing. 2021;16(1):1939937. DOI: 10.1080/17482631.2021.1939937

[3] Ayerle GM, Mattern E, Striebich S, Oganowski T, Ocker R, Haastert B, Schäfers R, Seliger G. Effect of alternatively designed hospital birthing rooms on the rate of vaginal births: Multicentre randomised controlled trial Be-Up. Women Birth. 2023 Sep;36(5):429-38. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2023.02.009

[4] Ayerle GM, Schäfers R, Mattern E, Striebich S, Haastert B, Vomhof M, Icks A, Ronniger Y, Seliger G. Effects of the birthing room environment on vaginal births and client-centred outcomes for women at term planning a vaginal birth: BE-UP, a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):641. DOI: 10.1186/s13063-018-2979-7

[5] Belliger A, Krieger DJ, editors. ANThology: Ein einführendes Handbuch zur Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie. Bielefeld: Transcript; 2006.

[6] Berg M, Goldkuhl L, Nilsson C, Wijk H, Gyllensten H, Lindahl G, Moberg KU, Begley C. Room4Birth – the effect of an adaptable birthing room on labour and birth outcomes for nulliparous women at term with spontaneous labour start: study protocol for a randomised controlled superiority trial in Sweden. Trials. 2019;20:629. DOI: 10.1186/s13063-019-3765-x

[7] Bohnsack R. Professionalisierung in praxeologischer Perspektive: Zur Eigenlogik der Praxis in Lehramt, Sozialer Arbeit und Frühpädagogik. Opladen, Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich; 2020.

[8] Bohnsack R, Nentwig-Gesemann I, Nohl AM, editors. Die dokumentarische Methode und ihre Forschungspraxis: Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007.

[9] Gaffer Y, Liell C. Handlungstheoretische und methodologische Aspekte der dokumentarischen Interpretation jugendkultureller Praktiken. In: Bohnsack R, Nentwig-Gesemann I, Nohl AM, editors. Die dokumentarische Methode und ihre Forschungspraxis: Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007. p. 183-207.

[10] Gesellschaft für Qualität in der außerklinischen Geburtshilfe e.V. (QUAG). Geburtenzahlen in Deutschland. [last accessed 2023 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.quag.de/quag/geburtenzahlen.htm

[11] Gesetz über das Studium und den Beruf von Hebammen: Hebammengesetz – HebG. [last accessed 2023 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/hebg_2020/BJNR175910019.html

[12] Hammond A, Homer CSE, Foureur M. Friendliness, functionality and freedom: Design characteristics that support midwifery practice in the hospital setting. Midwifery. 2017 Jul;50:133-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.03.025

[13] Häußling R, editor. Techniksoziologie: Eine Einführung. 2nd ed. Opladen, Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich; 2019. (utb Soziologie; 4184).

[14] Luegmair K. Handlungsleitende Orientierungen von Hebammen in verschiedenen Gebärräumen – eine qualitative Studie [dissertation]. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg; 2023.

[15] Luegmair K, Ayerle GM, Steckelberg A. Midwives' action-guiding orientation while attending hospital births - A scoping review. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2022 Dec;34:100778. DOI: 10.1016/j.srhc.2022.100778

[16] Luegmair K, Ayerle GM, Steckelberg A. Midwives’ practice guiding orientations when attending births in the clinical setting in Germany – a qualitative study. Forthcoming 2025.

[17] Nicklich M, Röbenack S, Sauer S, Schreyer J, Tihlarik A. Qualitative Social Research at a Distance: Potentials and Challenges of Virtual Interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2023;24(1):Art15. DOI: 10.17169/fqs-24.1.4010

[18] Nohl AM. Interview und dokumentarische Methode: Anleitungen für die Forschungspraxis. 4th ed. Wiesbaden: Springer VS; 2012. (Qualitative Sozialforschung).

[19] Nohl AM. Relationale Typenbildung und Mehrebenenvergleich: Neue Wege der dokumentarischen Methode. Wiesbaden: Springer VS; 2013. (Qualitative Sozialforschung).

[20] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Caesarean sections. [last accessed 2023 Oct 23]. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/caesarean-sections.htm

[21] Peterwerth NH, Halek M, Schäfers R. Intrapartum risk perception-A qualitative exploration of factors affecting the risk perception of midwives and obstetricians in the clinical setting. Midwifery. 2022 Mar;106:103234. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103234

[22] Rammert W. Technik – Handeln – Wissen: Zu einer pragmatistischen Technik- und Sozialtheorie. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: Springer VS; 2016.

[23] Schäffer B. „Kontagion“ mit dem Technischen. Zur dokumentarischen Interpretation der generationenspezifischen Einbindung in die Welt medientechnischer Dinge. In: Bohnsack R, Nentwig-Gesemann I, Nohl AM, editors. Die dokumentarische Methode und ihre Forschungspraxis: Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007. p. 45-67.

[24] Stone NI, Thomson G, Tegethoff D. Skills and knowledge of midwives at free-standing birth centres and home birth: A metaethnography. Women Birth. 2023;36(5):e481-94. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2023.03.010

[25] Thompson SM, Low LK, Budé L, de Vries R, Nieuwenhuijze M. Evaluating the effect of an educational intervention on student midwife selfefficacy for their role as physiological childbirth advocates. Nurse EducToday. 2021;96:104628. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104628

[26] Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19(6):349-57. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

[27] VERBI Software. MAXQDA. Available from: https://www.maxqda.de/

[28] Weyer J. Die Kooperation menschlicher Akteure und nicht-menschlicher Agenten: Ansatzpunkte einer Soziologie hybrider Systeme. Dortmund: Universität Dortmund; 2006. (Soziologischen Arbeitspapiere; 16).

[29] Witzel A. The Problem-Centered Interview. FQS. 2000;1(1):Article 22. DOI: 10.17169/fqs-1.1.1132

[30] World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme. WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;23(45):149-50. DOI: 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.07.007